Sonnet 46: Mine Eye and Heart Are at a Mortal War

|

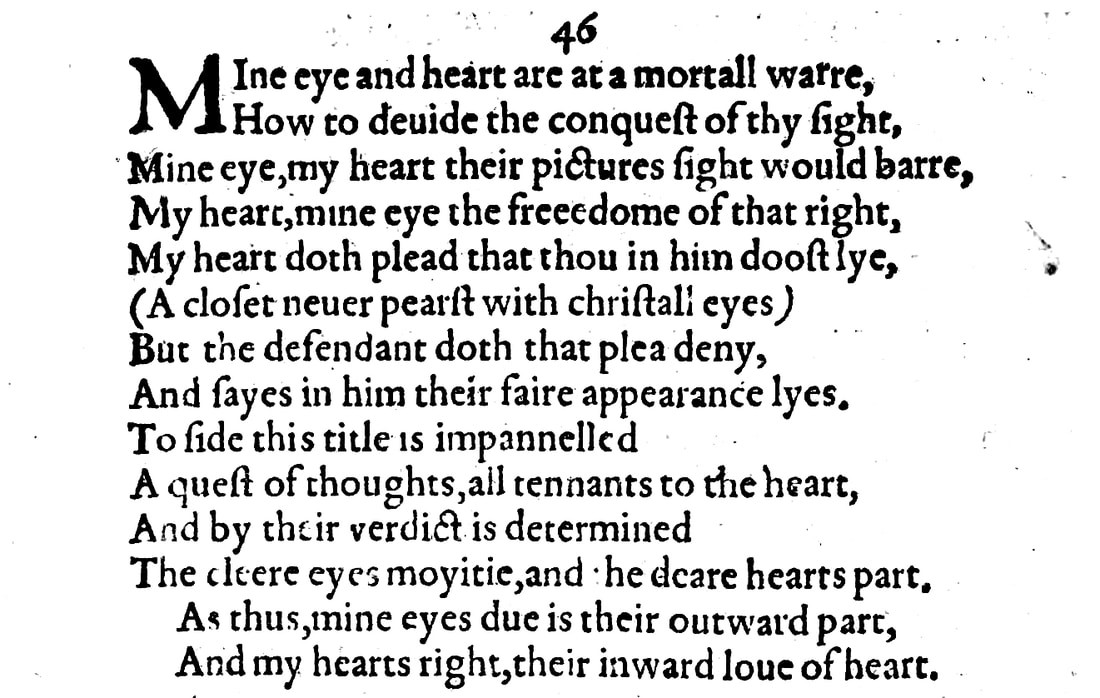

Mine eye and heart are at a mortal war

How to divide the conquest of thy sight: Mine eye my heart thy picture's sight would bar, My heart mine eye the freedom of that right. My heart doth plead that thou in him dost lie, A closet never pierced with crystal eyes, But the defendant doth that plea deny And says in him thy fair appearance lies. To side this title is impanelled A quest of thoughts, all tenants to the heart, And by their verdict is determined The clear eye's moiety and the dear heart's part As thus: mine eye's due is thy outward part And my heart's right thy inward love of heart. |

|

Mine eye and heart are at a mortal war

How to divide the conquest of thy sight: |

My eye and my heart are at a mortal war with each other over how to divide the spoils that come from the conquest of your sight.

Editors tend to point out that battles between the eye and the heart are a Renaissance commonplace, and so this poetic situation in which the eye and the heart argue over whom the young lover 'belongs' to and whether he therefore should be kept in the heart or in the eye is not an entirely original one. The dispute stems from the eye having seen the young man – which is here treated as a 'conquest' in its own right – and considering that the poem appears to be written while Shakespeare is away from his lover, this is likely to be in a picture. Sonnet 47, which directly follows on from Sonnet 46, will strongly support this supposition. |

|

Mine eye my heart thy picture's sight would bar,

|

My eye wants to ban the heart from looking at your picture...

Implied is because the eye doesn't want to let go of it. |

|

My heart mine eye the freedom of that right.

|

In response, my heart wants to bar – here in the sense more of deny – my eye the freedom of the right to do so, namely to stop it, the heart, from seeing your picture. In other words: my eye wants to stop the heart from seeing your picture, and my heart says that my eye has not right to do so.

|

|

My heart doth plead that thou in him dost lie,

A closet never pierced with crystal eyes; |

The legal overtones of the sonnet continue as the heart, here personified, now enters 'his' own plea by saying that you lie in him, and that he, my heart, is a closet which has never yet been pierced by any 'crystal' eyes, meaning no eye, no matter how clear and piercing, has ever been able to look inside a heart.

A 'closet' in Shakespeare's day is either a small private chamber or a chest where valuables are kept, which strengthens the idea of the heart being a private, secure, enclosed place, the innermost part of the human being, where therefore those things are kept that are of greatest value, including the much beloved young man. And the idea that the loved one resides in the lover's heart is one we have come across in Shakespeare before, most notably in the confidently hopeful Sonnet 22 and the much more complex and uncertain Sonnet 24. It, too, is, as we noted there, a poetic commonplace |

|

But the defendant doth that plea deny,

And says in him thy fair appearance lies. |

The eye, who is the defendant in this scenario, denies the plea entered by heart and says that on the contrary, your beauty resides in him.

The notion that 'beauty is in the eye of the beholder' is proverbial and although Shakespeare himself doesn't ever put it like that – the phrase as we know it today is first recorded in print in the 19th century – many poets before him and Shakespeare himself elsewhere in his work have said as much. |

|

To side this title is impannelled

A quest of thoughts, all tenants to the heart, |

In order to decide this case and the question of the legal entitlement to the possession of your image, a jury of thoughts is enlisted and these thoughts are all tenants to the heart, meaning that they are not impartial: they lease their metaphorical 'land' on which they can grow and prosper from the heart and so are in a sense beholden to the heart.

Many editors emend the Quarto Edition's 'side' in "To side this title" to a curtailed version of 'decide', so it reads "To 'cide this title..." There is, however, a perfectly valid dictionary definition of 'to side' as a transitive verb, meaning "to assign to either of two sides or parties" (The New Oxford English Dictionary), and even if there weren't and Shakespeare had effectively just made this up on the hop, it would still be perfectly clear what he means, so I see no good reason to mess with with his words here. And note that 'impannelled' is pronounced with four syllables. |

|

And by their verdict is determined

The clear eye's moiety and the dear heart's part As thus: |

And by the verdict of these thoughts is determined which part the clear eye receives and which part the dear heart receives, as follows:

A 'moiety' is defined as "a part or portion, especially a lesser share," (Oxford Dictionaries), and the fact that the eye appears to be given a smaller or less significant portion is not surprising since the jury of thoughts that makes the decision is skewed in favour of the heart. And here correspondingly 'determined' is also pronounced as four syllables. |

|

mine eye's due is thy outward part,

And my heart's right thy inward love of heart. |

The judgement – though not impartial and apparently unequal – seems fair: what is due to my eye is your outward appearance, and my heart has the right to keep and protect your inward love.

This is an obvious resolution, but it is also the first time the 'inward love of heart' of the young man is mentioned in this sonnet, and so the eye actually gets what it wants: your image. And so the verdict seems to bring about a new peace between eye and heart, as Sonnet 47 will shortly attest to. |

Sonnet 46 is the first in a second couple of sonnets that take a more abstract approach to dealing with separation, while employing a fairly established classical trope, in this case a conflict between the eye and the heart over which of these two should 'own' the young lover. Similar to Sonnet 44 in the previous pair, Sonnet 46 can ostensibly stand on its own, but it nevertheless serves as the foundation for its counterpart, Sonnet 47, which follows on from it directly and really needs to be read as an extension of it. We will therefore again look at both sonnets together in the next episode, whilst concentrating here on Sonnet 46.

The duality of outward beauty and inward worth is a recurring theme, not only for Shakespeare but in Renaissance poetry, and indeed in classical literature generally. In fact, we touched on it when we were discussing Sonnet 14, and noted there that in the ideal person of Shakespeare's era, these two aspects complement each other to strike an agreeable balance.

Sonnet 46 does not speak of 'inward worth' directly but in a similar way juxtaposes the young man's appearance with, in this instance, his love and resolves the conflict between the poet's eye and heart in the most obvious and straightforward way possible: your appearance belongs to my eye, your love belongs to my heart. There are certainly no surprises there.

Formally noteworthy is the legalese tone of the sonnet. Shakespeare every so often uses the language of court in his writing, and what is striking here is how this case is brought, heard, and judged. We don't know whether Shakespeare has given a great deal of thought to this and is consciously signalling to us how he views things, or whether he writes this sonnet more or less off the cuff, but what he presents us with is a fairly jealous and possessive eye that doesn't want to let go of the image of the young lover and share it with the heart. The heart then appears to bring the case to this imaginary court to claim his title in the young man, thus turning the eye into the defendant. They both give reasonable evidence and the panel of jurors then passes its judgement, whereby this jury is stacked from the outset in favour of the heart, which suggests that as far as Shakespeare is concerned, heart has and should have the upper hand.

This need hardly surprise us. Time and again in these sonnets, the young man's beauty is eulogised, only for a point then to be made that what really matters though is what's on the inside: virtue, truthfulness, constancy. Very soon, in Sonnet 54, Shakespeare will ask the youth the rhetorical question:

O how much more doth beauty beauteous seem

By that sweet ornament which truth doth give?

And it will be fascinating to note much later in the series, when Shakespeare talks about his mistress, the 'Dark Lady', how he repeatedly concedes that she is far from beautiful, but he loves her all the same.

With Sonnets 44 & 45, we felt we detected a certain detachment, and speculated that this may well have to do with Shakespeare having resigned himself to being away from his lover for an extended period, and that, with no direct stimuli for his sonneteering, he resorts to poetic commonplaces to keep himself occupied and to deal with his unsettled feelings for his young lover. Sonnet 46 very much aligns itself with this vein: it constructs a decent enough argument and displays the familiar compositional skill, but even at the time it is unlikely to have astounded.

It is only half of a pair though, and the real point of Sonnet 46 – what I said about it being able to stand alone notwithstanding – is actually being made in Sonnet 47, as we shall see very shortly...

The duality of outward beauty and inward worth is a recurring theme, not only for Shakespeare but in Renaissance poetry, and indeed in classical literature generally. In fact, we touched on it when we were discussing Sonnet 14, and noted there that in the ideal person of Shakespeare's era, these two aspects complement each other to strike an agreeable balance.

Sonnet 46 does not speak of 'inward worth' directly but in a similar way juxtaposes the young man's appearance with, in this instance, his love and resolves the conflict between the poet's eye and heart in the most obvious and straightforward way possible: your appearance belongs to my eye, your love belongs to my heart. There are certainly no surprises there.

Formally noteworthy is the legalese tone of the sonnet. Shakespeare every so often uses the language of court in his writing, and what is striking here is how this case is brought, heard, and judged. We don't know whether Shakespeare has given a great deal of thought to this and is consciously signalling to us how he views things, or whether he writes this sonnet more or less off the cuff, but what he presents us with is a fairly jealous and possessive eye that doesn't want to let go of the image of the young lover and share it with the heart. The heart then appears to bring the case to this imaginary court to claim his title in the young man, thus turning the eye into the defendant. They both give reasonable evidence and the panel of jurors then passes its judgement, whereby this jury is stacked from the outset in favour of the heart, which suggests that as far as Shakespeare is concerned, heart has and should have the upper hand.

This need hardly surprise us. Time and again in these sonnets, the young man's beauty is eulogised, only for a point then to be made that what really matters though is what's on the inside: virtue, truthfulness, constancy. Very soon, in Sonnet 54, Shakespeare will ask the youth the rhetorical question:

O how much more doth beauty beauteous seem

By that sweet ornament which truth doth give?

And it will be fascinating to note much later in the series, when Shakespeare talks about his mistress, the 'Dark Lady', how he repeatedly concedes that she is far from beautiful, but he loves her all the same.

With Sonnets 44 & 45, we felt we detected a certain detachment, and speculated that this may well have to do with Shakespeare having resigned himself to being away from his lover for an extended period, and that, with no direct stimuli for his sonneteering, he resorts to poetic commonplaces to keep himself occupied and to deal with his unsettled feelings for his young lover. Sonnet 46 very much aligns itself with this vein: it constructs a decent enough argument and displays the familiar compositional skill, but even at the time it is unlikely to have astounded.

It is only half of a pair though, and the real point of Sonnet 46 – what I said about it being able to stand alone notwithstanding – is actually being made in Sonnet 47, as we shall see very shortly...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!