Sonnet 14: Not From the Stars Do I My Judgement Pluck

|

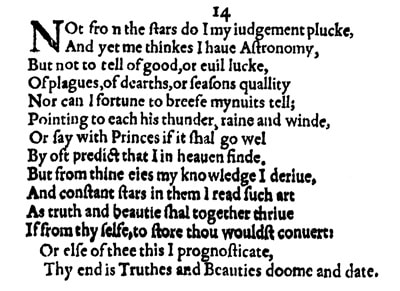

Not from the stars do I my judgement pluck,

And yet methinks I have astronomy, But not to tell of good or evil luck, Of plagues, of dearths, or seasons' quality; Nor can I fortune to brief minutes tell, Pointing to each his thunder, rain, and wind, Or say with princes if it shall go well, By oft predict that I in heaven find. But from thine eyes my knowledge I derive, And, constant stars, in them I read such art As truth and beauty shall together thrive If from thyself to store thou wouldst convert; Or else of thee this I prognosticate: Thy end is truth's and beauty's doom and date. |

|

Not from the stars do I my judgement pluck,

And yet methinks I have astronomy, |

I do not take my judgement – here by implication of you, what I am about to say about you and specifically about your future – from the stars, and yet I think I am capable of astrology.

Note the difference here in the meaning of the word 'astronomy' in Shakespeare's day compared to ours: we would describe the scientific observation and study of the stars and other celestial bodies as 'astronomy' and the prediction of a person's future or their destiny based on the constellation of the stars and the planets as 'astrology'. Here 'astronomy' is used to mean the latter, albeit with a caveat: |

|

But not to tell of good or evil luck,

Of plagues, of dearths, or seasons' quality; |

But this ability that I have does not lend itself to foretell good or bad luck – "evil" here meaning generally 'bad' – or to make predictions about plagues, famines as they would come about by a dearth of crops, or the quality of the seasons...

The plague was a constant threat to Elizabethan England and there as elsewhere in Europe caused enormous upheaval, killing large swathes of the population. It was therefore to be taken absolutely seriously. Similarly, in a largely agricultural society, predictions about dearths, which here means a shortage of food, and the 'quality of the seasons' – how the weather was going to pan out over the longer term – was of critical, existential importance, and many attempts to make such forecasts were made by means that had much more to do with fortune telling than with scientific meteorology. |

|

Nor can I fortune to brief minutes tell,

Pointing to each his thunder, rain, and wind, |

Nor can I make any predictions about the short term weather – as opposed to entire seasons – giving exact details for each moment or minute as to whether there will be thunderstorms, rain, or wind, for example...

Note that 'his' here refers to each brief minute. It is entirely common for Shakespeare to use the personal pronoun for things. |

|

Or say with princes if it shall go well,

By oft predict that I in heaven find. |

Nor can I say whether things will go well with princes; all and any of this by the frequent predictions that I can find in the heavens, as other fortune tellers do or claim to do.

|

|

But from thine eyes my knowledge I derive,

|

But I receive my knowledge – here again implied is a knowledge of the future – from your eyes...

|

|

And, constant stars, in them I read such art

As truth and beauty shall together thrive If from thyself to store thou wouldst convert. |

...and your eyes being like constant stars – as opposed to shifting planets, which would suggest less certainty in making any kind of prediction for the longer term – I read in them the following artful or skilful prediction: truth and beauty will thrive together in and through you if you allow yourself to be 'converted' or 'changed' from just yourself to the 'store' of you, meaning the preservation of yourself through procreation. In other words, and unsurprisingly, if you have children.

The concept of 'store' as the continuation of oneself has come up before in Sonnet 11: there the poet somewhat tartly suggested that the young man should "let those whom Nature hath not made for store," namely those who are "harsh, featureless, and rude, barrenly perish." If – and we cannot say for certain whether this is the case, but it would seem to make sense – Sonnet 14 was indeed received by the young man after Sonnet 11, then he would by now be firmly familiar with the expression in this context and readily understand these densely written lines. |

|

Or else of thee this I prognosticate:

|

Otherwise I predict this for you:

|

|

Thy end is truth's and beauty's doom and date.

|

your death – "thy end" – will be the downfall and termination of truth and beauty itself.

'Date' here means final date. The somewhat melodramatic prediction is of course to be seen in the context of the young man's status as a paragon of truth and beauty, so if his truth and beauty ends, then all truth and beauty ends. |

The at first glance curiously anticlimactic Sonnet 14 seems to take us a step back in any real or supposed trajectory that the sonnets so far have described, but it nevertheless offers an intriguing insight into the constellation between the poet and the young man, and may in fact hide more than meets the eye.

The reason we might feel inclined to see this poem as a step back from certainly the last one is that it tones itself down by comparison. And at this juncture it may be worth reminding ourselves that we cannot be certain, of course, that these sonnets were written and delivered and therefore received in the order they appear in the published sequence.

We've already discussed this at some length and so I don't want to go into it here in any great detail, but even if we assume – as we have reason to – that the Quarto Edition of 1609 was assembled according to some principle which grouped the Procreation Sonnets together and made sure that those that clearly come as pairs follow each other, it is still entirely possible that some of them got jumbled up and in fact appear out of sequence.

Having said that, the course of true love never did run smooth, as Shakespeare himself put it when he let Lysander say so to Hermia in A Midsummer Night's Dream, and it would be foolish and naive to expect a relationship such as the one between Shakespeare and the young man to simply follow an upward path in one straight line.

This not least because if the impression we have received so far is correct that the Procreation Sonnets do in fact chart the beginnings of any type of personal contact between the poet and the young man and that furthermore this contact at the start may well have been a purely transactional one, prompted quite possibly by a commission instigated by someone else, then following the particularly personal note of Sonnet 13 we need not be entirely surprised if the poet here takes a step back. Whether this is because he has been rebuked, or because he feels he needs to make sure he doesn't lose track of his commission, or for some other reason we don't and most likely will never know.

What we do know is that Sonnet 14 overall comes along much more in the vein of some of the earlier sonnets. It sets out an argument on the level of a metaphor, the metaphor being astrology – what Shakespeare calls astronomy – and the argument being that although I, the poet, am not reading the stars, I seem to have a skill much like astrology which allows me to foretell your future: by looking into your eyes instead of gazing at the stars, I can tell that your twin virtues of truthfulness – a quality of character – and beauty – a quality of appearance — will "together thrive" if you have children, and they will both be doomed if you don't.

These two qualities that complement each other would have been recognisable to a classically educated person as something of an ideal, and soon, in Sonnet 16, the poet will be invoking them again, albeit in a somewhat different tonality, when he talks about "inward worth" and "outward fair:" your inner strength, reliability, honesty and your outward beauty are things that to the classical mind and therefore to the Renaissance mind of Elizabethan England go together.

The nugget though, in this Sonnet 14, comes in the first line of the third quatrain: "But from thine eyes my knowledge I derive." And it is of interest and value to us for two reasons. Firstly, if we continue – as we have been doing – to listen primarily to the words and accept the words as the result of real-life circumstances, rather than, say, a purely abstract exercise in writing – and so far this has served us well and led to an appreciable consistency in the "information" we've gleaned from these sonnets – then here I, the poet, am saying that I derive my knowledge about you not from some random divination, but from looking into your eyes. And only one sonnet ago I have called you my dear love. And while it is of course entirely possible that neither of these two things are either significant or bear any relation to each other, much more obvious and therefore likely would be for them to be highly significant and directly related.

There comes a point in the process of getting to know and to love someone where you no longer simply look at them but where you gaze into their eyes. This can only happen if you are close to them physically, facing them and if they allow you to do so, in other words, if they themselves feel a familiarity with and proximity to you. If you try to look into the eyes of a stranger, they will think you are staring at them and either avert their eyes or whack you or both. And so of course it can be argued – quite easily – that in the domain of rhetorical devices and poetic language it would be ridiculous to assume that just because a poet says I've looked into your eyes he has actually done so, it could just as easily and justifiably be argued that a poet as attuned to his circumstances and his feelings as William Shakespeare, as dextrous and precise in his deployment of language, as skilled and evocative in his choice of words, would use the fact that the relationship that has been establishing itself between him and this young man has shifted to both support his task, which as far as we can tell still principally is to convince the young man to marry and have children, and at the same time to relate to him that something is changing.

Secondly, we've mentioned once or twice and just did so again the classical education we know Shakespeare has, and can assume the young man would have, enjoyed. And much as the twin qualities of inner worth and outer beauty are close to a trope that they would both instantly recognise, so is the metaphor of the lover's eyes as stars. And while it may be jumping the gun a bit to describe the young man here already as Shakespeare's lover in a contemporary sense, he has now called him "dear my love" and so it may well be the case that the first impression we get from this Sonnet 14 – that it is something of a step back on the trajectory these two are on – may not be wholly accurate. The code, such as it is, may just lie here for all who recognise it to see, and suggest to us, as observers four hundred years down the line, that actually something beautiful is either about to happen or already well underway.

And as you can no doubt tell, things are about to get rather exciting rather quickly and quite soon...

The reason we might feel inclined to see this poem as a step back from certainly the last one is that it tones itself down by comparison. And at this juncture it may be worth reminding ourselves that we cannot be certain, of course, that these sonnets were written and delivered and therefore received in the order they appear in the published sequence.

We've already discussed this at some length and so I don't want to go into it here in any great detail, but even if we assume – as we have reason to – that the Quarto Edition of 1609 was assembled according to some principle which grouped the Procreation Sonnets together and made sure that those that clearly come as pairs follow each other, it is still entirely possible that some of them got jumbled up and in fact appear out of sequence.

Having said that, the course of true love never did run smooth, as Shakespeare himself put it when he let Lysander say so to Hermia in A Midsummer Night's Dream, and it would be foolish and naive to expect a relationship such as the one between Shakespeare and the young man to simply follow an upward path in one straight line.

This not least because if the impression we have received so far is correct that the Procreation Sonnets do in fact chart the beginnings of any type of personal contact between the poet and the young man and that furthermore this contact at the start may well have been a purely transactional one, prompted quite possibly by a commission instigated by someone else, then following the particularly personal note of Sonnet 13 we need not be entirely surprised if the poet here takes a step back. Whether this is because he has been rebuked, or because he feels he needs to make sure he doesn't lose track of his commission, or for some other reason we don't and most likely will never know.

What we do know is that Sonnet 14 overall comes along much more in the vein of some of the earlier sonnets. It sets out an argument on the level of a metaphor, the metaphor being astrology – what Shakespeare calls astronomy – and the argument being that although I, the poet, am not reading the stars, I seem to have a skill much like astrology which allows me to foretell your future: by looking into your eyes instead of gazing at the stars, I can tell that your twin virtues of truthfulness – a quality of character – and beauty – a quality of appearance — will "together thrive" if you have children, and they will both be doomed if you don't.

These two qualities that complement each other would have been recognisable to a classically educated person as something of an ideal, and soon, in Sonnet 16, the poet will be invoking them again, albeit in a somewhat different tonality, when he talks about "inward worth" and "outward fair:" your inner strength, reliability, honesty and your outward beauty are things that to the classical mind and therefore to the Renaissance mind of Elizabethan England go together.

The nugget though, in this Sonnet 14, comes in the first line of the third quatrain: "But from thine eyes my knowledge I derive." And it is of interest and value to us for two reasons. Firstly, if we continue – as we have been doing – to listen primarily to the words and accept the words as the result of real-life circumstances, rather than, say, a purely abstract exercise in writing – and so far this has served us well and led to an appreciable consistency in the "information" we've gleaned from these sonnets – then here I, the poet, am saying that I derive my knowledge about you not from some random divination, but from looking into your eyes. And only one sonnet ago I have called you my dear love. And while it is of course entirely possible that neither of these two things are either significant or bear any relation to each other, much more obvious and therefore likely would be for them to be highly significant and directly related.

There comes a point in the process of getting to know and to love someone where you no longer simply look at them but where you gaze into their eyes. This can only happen if you are close to them physically, facing them and if they allow you to do so, in other words, if they themselves feel a familiarity with and proximity to you. If you try to look into the eyes of a stranger, they will think you are staring at them and either avert their eyes or whack you or both. And so of course it can be argued – quite easily – that in the domain of rhetorical devices and poetic language it would be ridiculous to assume that just because a poet says I've looked into your eyes he has actually done so, it could just as easily and justifiably be argued that a poet as attuned to his circumstances and his feelings as William Shakespeare, as dextrous and precise in his deployment of language, as skilled and evocative in his choice of words, would use the fact that the relationship that has been establishing itself between him and this young man has shifted to both support his task, which as far as we can tell still principally is to convince the young man to marry and have children, and at the same time to relate to him that something is changing.

Secondly, we've mentioned once or twice and just did so again the classical education we know Shakespeare has, and can assume the young man would have, enjoyed. And much as the twin qualities of inner worth and outer beauty are close to a trope that they would both instantly recognise, so is the metaphor of the lover's eyes as stars. And while it may be jumping the gun a bit to describe the young man here already as Shakespeare's lover in a contemporary sense, he has now called him "dear my love" and so it may well be the case that the first impression we get from this Sonnet 14 – that it is something of a step back on the trajectory these two are on – may not be wholly accurate. The code, such as it is, may just lie here for all who recognise it to see, and suggest to us, as observers four hundred years down the line, that actually something beautiful is either about to happen or already well underway.

And as you can no doubt tell, things are about to get rather exciting rather quickly and quite soon...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!