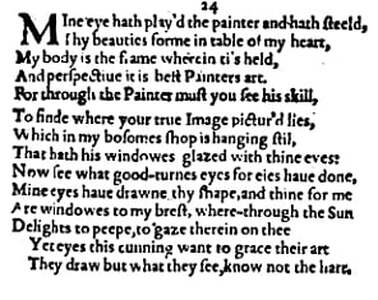

Sonnet 24: Mine Eye Hath Played the Painter and Hath Stelled

|

Mine eye hath played the painter and hath stelled

Thy beauty's form in table of my heart; My body is the frame wherein 'tis held, And perspective, it is best painter's art; For through the painter must you see his skill To find where your true image pictured lies, Which in my bosom's shop is hanging still, That hath his windows glazed with thine eyes. Now see what good turns eyes for eyes have done: Mine eyes have drawn thy shape, and thine for me Are windows to my breast, wherethrough the sun Delights to peep, to gaze therein on thee. Yet eyes this cunning want to grace their art: They draw but what they see, know not the heart. |

|

Mine eye hath played the painter and hath stelled

Thy beauty's form in table of my heart, |

My eye has played the painter and has drawn an image of your beauty on the board that is my heart.

'Stell' as a verb is fairly uncommon, it means to put, or to fix, but also to delineate or portray. The idea is that the poet's eye has made a portrait of the young man – perhaps similar to the at the time very fashionable miniatures – which would have been painted on a piece of wood, rather than on a canvas. |

|

My body is the frame wherein 'tis held

|

My body acts as the picture's frame...

|

|

And perspective, it is best painter's art;

|

...and the depiction of you is done with the highest painterly skill.

It is perhaps worth noting that 'perspective' – here used to quite generally mean the truthful representation of what the eye sees – is a source of great fascination for artists of the late 16th and early 17th century and in places extremely skilfully employed to achieve trompe-l'oeil effects or to 'hide' objects or people within paintings. Perspective drawing and painting in itself is by that time less than two hundred years old and of unparalleled significance to Renaissance art and architecture. |

|

For through the painter must you see his skill

To find where your true image pictured lies, |

It is, after all, through the painter's eyes and his art that you get to see a true picture or reflection of yourself, rather than, say, through a mirror.

It may not be incidental, but indeed intentional, that this idea, that when you look into someone's eye and you see yourself reflected in it, you are not only looking at a reflection of yourself, but you are doing so through the profound mirror of your opposite's soul into which you are therefore also gazing, goes right back to Greek antiquity, and is something that Shakespeare, with his classical schooling is very likely to have known and consciously used here. |

|

Which in my bosom's shop is hanging still

|

The picture – which is painted onto my heart – is and will therefore always be 'hanging' or living in my breast which thus acts as a shop or perhaps more precisely workshop or atelier where an artist would keep and also exhibit their art.

The 'still' here – as every so often in Shakespeare – has a meaning more of 'always' with a continuous vector into the future, rather than our understanding of something that was so in the past and is so now, but may or may not continue to be so into the future. |

|

That hath his windows glazed with thine eyes.

|

And the windows to this shop or workshop are glazed with your eyes.

'His' refers to the shop – again, it is not uncommon for Shakespeare to use a personal pronoun for an object – and glazed is pronounced with two syllables: glazèd. |

|

Now see what good turns eyes for eyes have done:

|

Now see what favours or mutually beneficial deeds – good turns – our eyes have done for each other:

|

|

Mine eyes have drawn thy shape, and thine for me

Are windows to my breast wherethrough the sun Delights to peep, to gaze therein on thee. |

My eyes have drawn you, and your eyes act as the windows to my breast, through which the sun enjoys looking at you, because that is where the picture that my eyes have made of you is hanging.

|

|

Yet eyes this cunning want to grace their art:

They draw but what they see, know not the heart. |

But eyes lack one particular skill to make their art perfect: they can only draw what they see, they cannot actually know what goes on inside the heart of the person they draw.

'Cunning' here means 'skill' or 'ability', what in the Greek tradition would have been considered a techne, from which we derive our word 'technology' and indeed 'technique', rather than necessarily something underhand or an ill-intentioned trickery. |

With the complex and in its conclusion quietly insightful Sonnet 24, William Shakespeare looks more closely at what is happening between him and the young man whom he has declared his passion for, and he does so in a tone that manages to be both hopeful and realistic – so as not to say resigned – at the same time. It spreads the short shadow of doubt that Sonnet 23 had already tentatively cast over the relationship, but it still does so in the subtlest of ways, leaving plenty of room for the renewed optimism that will follow briefly with Sonnet 25.

Absolutely most impactful here in Sonnet 24 is the final couplet. The realisation that, no matter how smitten I am by your beauty and although I metaphorically keep a picture of you in my heart, I actually don't know how you feel.

This goes a long way to answering one of the principal questions we have been asking ourselves for a while now: how does the young man feel about all this, and about Shakespeare? In Sonnet 23 we got the impression that all is not entirely hunky-dory, that William Shakespeare felt the need to both excuse his own inability to speak the right words at the right time and to educate the young man in the ways of a more refined love, and here now we are left with this devastating insight: my eyes feed you into my heart, I am here holding on to my love for you, but I don't know if you love me. You don't tell me, or show me through your actions, otherwise I would know. You stay aloof enough for me to remain unsure.

When I, your podcaster, Sebastian Michael, researched and wrote my play The Sonneteer, which is entirely about this relationship, I quite soon started to get the feeling that this was going to be a play as much about power as it is about passion, and ultimately it revealed itself to be even about possession. We are not at possession yet, but power begins to make itself felt: we saw a glint of it in Sonnet 23, when William Shakespeare was left tongue-tied and had to explain how it is that he doesn't come up with the right words, which, as we noted, suggests that the young man has either criticised or ridiculed or compared him unfavourably to someone else, and here now we come to understand that, after all these sonnets, after all this pouring out of admiration, adulation, amorisation, if you allow me to coin such a term here, Shakespeare has not actually got back all that much. In Sonnet 22 we wondered about this, we wondered whether Shakespeare saying about the young man and his heart "thou gavest me thine, not to give back again" was wishful thinking or rooted in something that offered him certainty, and here now we are left in no doubt that there is doubt, that maybe the young man hasn't actually done or said anything to allow Shakespeare to know for sure where he's at.

Or, indeed, maybe Shakespeare felt sure then, but doesn't feel sure now; maybe the young man has since done or said things that make Shakespeare come out with these two lines of abject reality check. We don't know. We only have the words, but the words here take a turn towards limbo: from the heaven of knowing or at least believing or even just believing that I could believe that my heart is in yours and yours just as much in mine I am now in a place where I don't know.

It is not altogether too adventurous to infer that the complexity of this sonnet is a direct reflection of the by now complex relationship. What am I, the poet, William Shakespeare, here presenting: I look at you and the way I see you is how I then preserve you as a picture in my heart. To understand who you really are you need to look at that picture through me: it is a truer reflection of you than any other that is available to you. Your eyes, meanwhile, are windows to my heart, and through these windows the sun gets to gaze on you, which to do it finds delightful. The sun is the life-giving source of energy and light for us all, so if the sun gazes on you, then so does our known universe, our world, everyone: the world, through your eyes gets to see you as you are because of how I depict you. But – alas – I cannot know who you really are, because it is after all only my eyes that have drawn you and they cannot know your heart. If I am to know your heart, then something other than my eyes has to be involved, it cannot be just about your appearance and my perception of you.

It is almost as if – to pick up on the anachronistic fairground metaphor we left off with in the last sonnet – William Shakespeare had wandered into a hall of mirrors where he spotted his young lover and now is trying to work out what is what and who is who and where is where. And these are not unusual disorientations when you are in love.

Editors like to point out that the connection between the heart and the eye is a Renaissance commonplace, and we already observed that perspective is of unambiguous importance to the art of the day, so it is possible, certainly in theory, that Shakespeare here mostly just goes off on an exercise of poetic acrobatics, but no sooner do you put this sonnet into the context of what has gone before and what comes next than you realise just how unlikely this is. Nothing is certain, we know, but this is a good moment to remind ourselves that in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. And knowing how we got here and looking out towards what follows, the much more likely 'explanation' for this poem and its existence and its unnerving complexity is that the relationship between William Shakespeare and his young man absolutely exists and has absolutely just got unnervingly complex.

There is one specific detail about Sonnet 24 which is worth pointing out: Sonnet 24 is the first and only sonnet in the whole series to use both the formal address 'you' and 'you' and the informal address 'thou', 'thy' and 'thine'. Whether this is significant or not, we don't know, whether it is conscious or not, we don't know, we can't say for certain that Shakespeare has made an active decision to use 'you' in the first two lines of the second quatrain:

For through the painter must you see his skill

To find where your true image pictured lies

But we noted before that when Shakespeare switched from 'thou' to 'you', that this happened in sonnets where one might argue a line was being crossed that hadn't previously been crossed. The first time I, William Shakespeare, use 'you' is in Sonnet 13, which also happens to be the first one where I call the young man 'love' and 'dear my love'. And we ventured that there is a possibility that Shakespeare, being so much more familiar in his words, is signalling to the young man that he is aware of his status in relation to the young man who is, as far as anyone can tell, almost certain to be a young nobleman; that Shakespeare uses the formal form of address to soften the impact of the much more intimate words he is using inside the poem.

The second time Shakespeare uses 'you' is in Sonnets 15 and 16, where he says to the young man:

And all in war with Time for love of you,

As he takes from you I engraft you new.

And again, these are two sonnets where Shakespeare gets much closer to being intimate, verbally, with the young man. Here in Sonnet 24 that isn't really the case, we can't really say that this sonnet is particularly intimate, or risky, or daring,, but it is particularly complex, and so the use of the mixed pronouns is perhaps an indication of the level of complexity that the relationship has now reached. It could be argued that for me, the poet, to say to the young nobleman that it is through my eyes only that he can see his true self, is quite a presumptuous suggestion and it could potentially be for this reason that Shakespeare employs the same technique to use the more formal you to soften the impact of this quite bold assertion.

It should be emphasised though that these elaborations are in effect conjecture: we really don't know whether Shakespeare meant to signal anything, or whether it just happened in the process of writing. Even if Shakespeare did so unconsciously though, there is some significance to this, because the subconscious mind is incredibly powerful and we very often say things without actually realising it and through saying them and the way we are saying them impart information about how we fell and where we are at.

And note one particularly interesting detail, which mostly, if not indeed entirely, gets overlooked: these 'good turns' that eyes for eyes have done here are by no means equal. My eyes have drawn your shape and they have have done so "in table of my heart." And this portrait of you that my eyes have drawn, for which read painted, which is after all something that requires careful study and execution is and as far as I'm concerned will be hanging "in my bosom's shop."

Your eyes, by contrast, are merely windows to my breast. The sun and therefore the world looks through your eyes onto my heart where you are pictured by my eyes. Your eyes serve both as a window for the world and as a mirror to yourself as I see you, but they do not do anything to reflect me. Certainly not directly.

Does it all make sense? Logically, probably not so much. This is a recurring theme we get with these sonnets, that logic is not William Shakespeare's strongest suit. But William Shakespeare might be laughing at us – if he isn't turning in his grave – for being so meticulous and precise in our attempt at understanding just what exactly he is trying to say.

We don't know how long Shakespeare laboured over each of these sonnets, but we do know that he wrote fast. We know that in order for his plays to have been performed at the times when they were entered in the Stationers' Register, he had to churn them out at a rate of several a year, sometimes within weeks of each other. We don't know how many of these sonnets are actually addressed to the Fair Youth, but our common understanding is that it is all or if not all then most of the first 126. And we will learn, quite a bit further down the line, in Sonnet 104, that by then the two men have known each other for three years. So bearing in mind his theatrical output, his work as an actor, which took him on slow and arduous tours where he was on horseback for long periods, and the uneven nature of this as of almost any relationship, which clearly goes through phases of higher and lower intensity, we can assume that he wrote some of them quickly, within a day or two, without having all that much time to rewrite or revise them, or even to think them through in their actual logical argumentation.

These are, lest we forget, poems of passion after all, and while they often give way to reflection, to observation, and to what we might today consider self-evaluation, they do principally stem from the emotional turmoil that comes with being in love. And love has yet to find a way to be purely rational.

What matters then, here as elsewhere in the canon where we struggle to make sense, is not so much the sense itself as the sentiment overall. And here, as elsewhere, the sentiment is entirely clear: I, the poet, William Shakespeare, am in love, but I cannot at this point in these proceedings be at all sure whether you, the young man I am in love with, are also in love with me. And if so, to what degree, in what way: I love you but I do not know your heart. If this sounds like a bump in the road, then that's because it most certainly is.

We're about to pick up a dizzying speed with the newly assured and joyfully assertive Sonnet 25, but what goes up must come down and there is another, and much more painful thud just round the corner...

Absolutely most impactful here in Sonnet 24 is the final couplet. The realisation that, no matter how smitten I am by your beauty and although I metaphorically keep a picture of you in my heart, I actually don't know how you feel.

This goes a long way to answering one of the principal questions we have been asking ourselves for a while now: how does the young man feel about all this, and about Shakespeare? In Sonnet 23 we got the impression that all is not entirely hunky-dory, that William Shakespeare felt the need to both excuse his own inability to speak the right words at the right time and to educate the young man in the ways of a more refined love, and here now we are left with this devastating insight: my eyes feed you into my heart, I am here holding on to my love for you, but I don't know if you love me. You don't tell me, or show me through your actions, otherwise I would know. You stay aloof enough for me to remain unsure.

When I, your podcaster, Sebastian Michael, researched and wrote my play The Sonneteer, which is entirely about this relationship, I quite soon started to get the feeling that this was going to be a play as much about power as it is about passion, and ultimately it revealed itself to be even about possession. We are not at possession yet, but power begins to make itself felt: we saw a glint of it in Sonnet 23, when William Shakespeare was left tongue-tied and had to explain how it is that he doesn't come up with the right words, which, as we noted, suggests that the young man has either criticised or ridiculed or compared him unfavourably to someone else, and here now we come to understand that, after all these sonnets, after all this pouring out of admiration, adulation, amorisation, if you allow me to coin such a term here, Shakespeare has not actually got back all that much. In Sonnet 22 we wondered about this, we wondered whether Shakespeare saying about the young man and his heart "thou gavest me thine, not to give back again" was wishful thinking or rooted in something that offered him certainty, and here now we are left in no doubt that there is doubt, that maybe the young man hasn't actually done or said anything to allow Shakespeare to know for sure where he's at.

Or, indeed, maybe Shakespeare felt sure then, but doesn't feel sure now; maybe the young man has since done or said things that make Shakespeare come out with these two lines of abject reality check. We don't know. We only have the words, but the words here take a turn towards limbo: from the heaven of knowing or at least believing or even just believing that I could believe that my heart is in yours and yours just as much in mine I am now in a place where I don't know.

It is not altogether too adventurous to infer that the complexity of this sonnet is a direct reflection of the by now complex relationship. What am I, the poet, William Shakespeare, here presenting: I look at you and the way I see you is how I then preserve you as a picture in my heart. To understand who you really are you need to look at that picture through me: it is a truer reflection of you than any other that is available to you. Your eyes, meanwhile, are windows to my heart, and through these windows the sun gets to gaze on you, which to do it finds delightful. The sun is the life-giving source of energy and light for us all, so if the sun gazes on you, then so does our known universe, our world, everyone: the world, through your eyes gets to see you as you are because of how I depict you. But – alas – I cannot know who you really are, because it is after all only my eyes that have drawn you and they cannot know your heart. If I am to know your heart, then something other than my eyes has to be involved, it cannot be just about your appearance and my perception of you.

It is almost as if – to pick up on the anachronistic fairground metaphor we left off with in the last sonnet – William Shakespeare had wandered into a hall of mirrors where he spotted his young lover and now is trying to work out what is what and who is who and where is where. And these are not unusual disorientations when you are in love.

Editors like to point out that the connection between the heart and the eye is a Renaissance commonplace, and we already observed that perspective is of unambiguous importance to the art of the day, so it is possible, certainly in theory, that Shakespeare here mostly just goes off on an exercise of poetic acrobatics, but no sooner do you put this sonnet into the context of what has gone before and what comes next than you realise just how unlikely this is. Nothing is certain, we know, but this is a good moment to remind ourselves that in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. And knowing how we got here and looking out towards what follows, the much more likely 'explanation' for this poem and its existence and its unnerving complexity is that the relationship between William Shakespeare and his young man absolutely exists and has absolutely just got unnervingly complex.

There is one specific detail about Sonnet 24 which is worth pointing out: Sonnet 24 is the first and only sonnet in the whole series to use both the formal address 'you' and 'you' and the informal address 'thou', 'thy' and 'thine'. Whether this is significant or not, we don't know, whether it is conscious or not, we don't know, we can't say for certain that Shakespeare has made an active decision to use 'you' in the first two lines of the second quatrain:

For through the painter must you see his skill

To find where your true image pictured lies

But we noted before that when Shakespeare switched from 'thou' to 'you', that this happened in sonnets where one might argue a line was being crossed that hadn't previously been crossed. The first time I, William Shakespeare, use 'you' is in Sonnet 13, which also happens to be the first one where I call the young man 'love' and 'dear my love'. And we ventured that there is a possibility that Shakespeare, being so much more familiar in his words, is signalling to the young man that he is aware of his status in relation to the young man who is, as far as anyone can tell, almost certain to be a young nobleman; that Shakespeare uses the formal form of address to soften the impact of the much more intimate words he is using inside the poem.

The second time Shakespeare uses 'you' is in Sonnets 15 and 16, where he says to the young man:

And all in war with Time for love of you,

As he takes from you I engraft you new.

And again, these are two sonnets where Shakespeare gets much closer to being intimate, verbally, with the young man. Here in Sonnet 24 that isn't really the case, we can't really say that this sonnet is particularly intimate, or risky, or daring,, but it is particularly complex, and so the use of the mixed pronouns is perhaps an indication of the level of complexity that the relationship has now reached. It could be argued that for me, the poet, to say to the young nobleman that it is through my eyes only that he can see his true self, is quite a presumptuous suggestion and it could potentially be for this reason that Shakespeare employs the same technique to use the more formal you to soften the impact of this quite bold assertion.

It should be emphasised though that these elaborations are in effect conjecture: we really don't know whether Shakespeare meant to signal anything, or whether it just happened in the process of writing. Even if Shakespeare did so unconsciously though, there is some significance to this, because the subconscious mind is incredibly powerful and we very often say things without actually realising it and through saying them and the way we are saying them impart information about how we fell and where we are at.

And note one particularly interesting detail, which mostly, if not indeed entirely, gets overlooked: these 'good turns' that eyes for eyes have done here are by no means equal. My eyes have drawn your shape and they have have done so "in table of my heart." And this portrait of you that my eyes have drawn, for which read painted, which is after all something that requires careful study and execution is and as far as I'm concerned will be hanging "in my bosom's shop."

Your eyes, by contrast, are merely windows to my breast. The sun and therefore the world looks through your eyes onto my heart where you are pictured by my eyes. Your eyes serve both as a window for the world and as a mirror to yourself as I see you, but they do not do anything to reflect me. Certainly not directly.

Does it all make sense? Logically, probably not so much. This is a recurring theme we get with these sonnets, that logic is not William Shakespeare's strongest suit. But William Shakespeare might be laughing at us – if he isn't turning in his grave – for being so meticulous and precise in our attempt at understanding just what exactly he is trying to say.

We don't know how long Shakespeare laboured over each of these sonnets, but we do know that he wrote fast. We know that in order for his plays to have been performed at the times when they were entered in the Stationers' Register, he had to churn them out at a rate of several a year, sometimes within weeks of each other. We don't know how many of these sonnets are actually addressed to the Fair Youth, but our common understanding is that it is all or if not all then most of the first 126. And we will learn, quite a bit further down the line, in Sonnet 104, that by then the two men have known each other for three years. So bearing in mind his theatrical output, his work as an actor, which took him on slow and arduous tours where he was on horseback for long periods, and the uneven nature of this as of almost any relationship, which clearly goes through phases of higher and lower intensity, we can assume that he wrote some of them quickly, within a day or two, without having all that much time to rewrite or revise them, or even to think them through in their actual logical argumentation.

These are, lest we forget, poems of passion after all, and while they often give way to reflection, to observation, and to what we might today consider self-evaluation, they do principally stem from the emotional turmoil that comes with being in love. And love has yet to find a way to be purely rational.

What matters then, here as elsewhere in the canon where we struggle to make sense, is not so much the sense itself as the sentiment overall. And here, as elsewhere, the sentiment is entirely clear: I, the poet, William Shakespeare, am in love, but I cannot at this point in these proceedings be at all sure whether you, the young man I am in love with, are also in love with me. And if so, to what degree, in what way: I love you but I do not know your heart. If this sounds like a bump in the road, then that's because it most certainly is.

We're about to pick up a dizzying speed with the newly assured and joyfully assertive Sonnet 25, but what goes up must come down and there is another, and much more painful thud just round the corner...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!