Sonnet 12: When I Do Count the Clock that Tells the Time

|

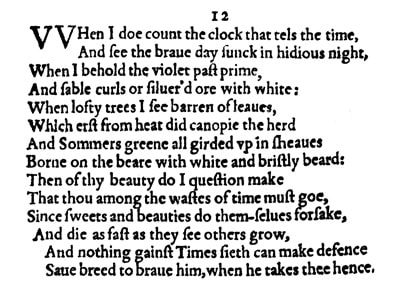

When I do count the clock that tells the time

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night, When I behold the violet past prime And sable curls all silvered ore with white; When lofty trees I see, barren of leaves, Which erst from heat did canopy the herd, And summer's green all girded up in sheaves, Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard, Then of thy beauty do I question make That thou among the wastes of time must go, Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake And die as fast as they see others grow; And nothing gainst Time's scythe can make defence Save breed to brave him when he takes thee hence. |

|

When I do count the clock that tells the time

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night, |

When I look at the clock and notice how time passes and when I see how day turns into night.

'Brave' here means strong, beautiful, glorious, as contrasted by the 'hideous night', whereby 'hideous' here is to be understood not so much in the sense of 'extremely ugly' that we would use it for today, but more generally unpleasant and dark. And note the 'tick tock' contained in the sound of the first line: "When I do count the clock that tells the time," with its beautifully contained onomatopoeia. |

|

When I behold the violet past prime

|

When I look at the violet when it is past its prime, meaning that it is wilting or indeed wilted...

|

|

And sable curls all silvered ore with white;

|

...and black curls all silvered-over with white; referring of course to the dark or indeed black curls of a beautiful young person, turned white with old age...

|

|

When lofty trees I see, barren of leaves,

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd, |

....when I see tall tress that now stand bare without their leaves, which a while ago lent shade to the animals on the field...

'Canopy' is a verb here, meaning 'to lend a canopy' or 'to cover'. |

|

And summer's green all girded up in sheaves

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard; |

And the green blades of grass grown for its grain, such as barley or wheat – 'summer's green' – now bound up in sheaves and carried on the wagon, with the bristles of their awns resembling the white beard of an old person...

|

|

Then of thy beauty do I question make

That thou among the wastes of time must go, |

...then I do wonder about your beauty and that you will have to go to waste with everything else that is subject to the ravages time...

|

|

Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake

And die as fast as they see others grow; |

...because sweet things – for which read all things lovely and pleasing – and beauties – for which read all things beautiful, including you – forsake themselves – for which read leave themselves in their state of sweetness and beauty, and die just as fast as they can observe the new or young sweets and beauties around them grow.

|

|

And nothing gainst Time's scythe can make defence

Save breed to brave him when he takes thee hence. |

And nothing can defend you against the scythe of Time which cuts everything down eventually, except breeding children who can stand up him – time is personified here – when he, Time, comes to get you.

The way Time is portrayed here as a character very much resembles the classical personification of Death: as a reaper with a scythe. |

In the gorgeous, pensive, and mature Sonnet 12, William Shakespeare finds a whole new register to relate a message that is by now familiar, and he reveals something of the depth and melancholy that will become a feature of future poems in the series.

This beautiful meditation on time is the first of its kind we encounter and the only one to form part of the Procreation Sonnets. Gone – at least for the time-being – is any flamboyance or frivolousness. Any notion that Shakespeare may be joking, or that he may be hinting at anything other than a fundamental truth, or that he may be speaking on somebody else's behalf here and his heart may not really be in it: none of this here seems to apply. Instead, we get great sincerity and detailed observation leading up to a conclusion we can pretty much foresee in the context of what has been said before, but even this, the final couplet, is almost shocking in its heartfelt authenticity.

And so the sonnet, while it clearly belongs in the sequence and obviously and unequivocally emphasises the need to have children in order to effectively conquer death, does so with a whole new level of sincerity. When some of the previous eleven sonnets may have suggested to us that Shakespeare is perhaps going through the motions a bit, that he is possibly showing off his verbal dexterity, that he may not really care all that much about some of what he nevertheless craftily composes, with Sonnet 12 we get the voice of a man who reflects on time and its passing and its unrelenting motion towards death with insight and sorrow.

As ever, we still need to be careful not to read more into these fourteen lines than are actually there, and it remains the case that how we 'feel' about poetry is subjective. But what is evident almost beyond reasonable doubt is that the poetry employed here is of a different quality, as in different kind or type. Hyperbole is absent: nothing is exaggerated. Similes are absent: nothing is directly compared to anything else; and metaphors are sparse and specific. The clock really does tell the time. The day really does turn into night. The violet really does go past its prime and wilt. And sable curls really do get silvered over with white. The trees do lose their leaves which before were able to lend shade to the herd, and it is only when we hear the barley and the wheat referred to as "summer's green" and their awns as a "bristly beard" that we get anything beyond poetic but literal language.

This is different to anything that's gone before. And it surely is significant. In what way though, we don't know yet. This sonnet does not tell us much about the relationship between the poet and the young man, nor does it tell us anything at all about the young man. It does tell us something about Shakespeare though: it tells us with some appreciable degree of certainty that he senses this passing of the time, that he has thought about this, that the observations he is making are, to him, real. Do we have any proof of this? Only what is in the words, but these words speak a remarkably clear language that is at once evocative and profoundly moving. And it's a language that we shall encounter again and to even greater depth before too long...

This beautiful meditation on time is the first of its kind we encounter and the only one to form part of the Procreation Sonnets. Gone – at least for the time-being – is any flamboyance or frivolousness. Any notion that Shakespeare may be joking, or that he may be hinting at anything other than a fundamental truth, or that he may be speaking on somebody else's behalf here and his heart may not really be in it: none of this here seems to apply. Instead, we get great sincerity and detailed observation leading up to a conclusion we can pretty much foresee in the context of what has been said before, but even this, the final couplet, is almost shocking in its heartfelt authenticity.

And so the sonnet, while it clearly belongs in the sequence and obviously and unequivocally emphasises the need to have children in order to effectively conquer death, does so with a whole new level of sincerity. When some of the previous eleven sonnets may have suggested to us that Shakespeare is perhaps going through the motions a bit, that he is possibly showing off his verbal dexterity, that he may not really care all that much about some of what he nevertheless craftily composes, with Sonnet 12 we get the voice of a man who reflects on time and its passing and its unrelenting motion towards death with insight and sorrow.

As ever, we still need to be careful not to read more into these fourteen lines than are actually there, and it remains the case that how we 'feel' about poetry is subjective. But what is evident almost beyond reasonable doubt is that the poetry employed here is of a different quality, as in different kind or type. Hyperbole is absent: nothing is exaggerated. Similes are absent: nothing is directly compared to anything else; and metaphors are sparse and specific. The clock really does tell the time. The day really does turn into night. The violet really does go past its prime and wilt. And sable curls really do get silvered over with white. The trees do lose their leaves which before were able to lend shade to the herd, and it is only when we hear the barley and the wheat referred to as "summer's green" and their awns as a "bristly beard" that we get anything beyond poetic but literal language.

This is different to anything that's gone before. And it surely is significant. In what way though, we don't know yet. This sonnet does not tell us much about the relationship between the poet and the young man, nor does it tell us anything at all about the young man. It does tell us something about Shakespeare though: it tells us with some appreciable degree of certainty that he senses this passing of the time, that he has thought about this, that the observations he is making are, to him, real. Do we have any proof of this? Only what is in the words, but these words speak a remarkably clear language that is at once evocative and profoundly moving. And it's a language that we shall encounter again and to even greater depth before too long...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!