Sonnet 5: Those Hours That With Gentle Work Did Frame

|

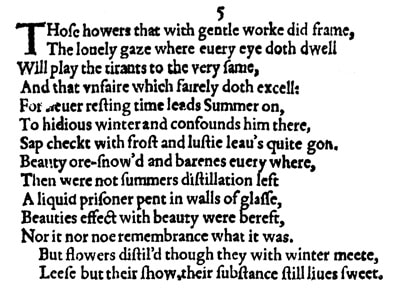

Those hours that with gentle work did frame

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell Will play the tyrants to the very same And that unfair which fairly doth excel. For never-resting time leads summer on To hideous winter and confounds him there, Sap checked with frost, and lusty leaves quite gone, Beauty oresnowed and bareness everywhere. Then, were not summer's distillation left, A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass, Beauty's effect with beauty were bereft: Nor it nor no remembrance what it was. But flowers distilled, though they with winter meet, Leese but their show, their substance still lives sweet. |

|

Those hours that with gentle work did frame

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell |

Those same hours that carefully crafted – "did frame" – the lovely face which attracts the looks of everybody...

Interesting here is that 'gaze' is used not to mean the act or state of looking – that's taken care of by the phrase "every eye doth dwell" – but the object being looked at by every eye, here the young man's face. PRONUNCIATION: Note that hours here has two syllables: hou-èrs. |

|

Will play the tyrants to the very same

|

...those same hours will also play the tyrants to this lovely face of yours...

|

|

And that unfair which fairly doth excel.

|

...and in their tyrannical way take away the beauty of that which now excels at being beautiful, namely you.

This is a brilliantly Shakespearean construction: he uses 'unfair' as a verb to mean 'make unfair', which means to 'make not beautiful', and he applies it to that "which fairly doth excel," giving this a double meaning. That which fairly doth excel is that which excels at being fair – is exceedingly beautiful – and also that which excels in a compelling way. 'Fairly' thus also becomes an adjective of understated appreciation, as in: this is fairly good, to mean it is in fact excellent. |

|

For never-resting time leads summer on

To hideous winter and confounds him there, |

Both time and summer are personified here, though in the Quarto Edition only Summer is capitalised: Time leads Summer on to become an ugly, unpleasant Winter and there overthrows or defeats – "confounds" – him.

|

|

Sap checked with frost, and lusty leaves quite gone,

|

Summer here is represented by a tree: its rich sap in winter is 'checked" – held back – by frost, and the lush, green leaves are "quite gone": they have long since been blown away by the autumn winds.

'Lusty' here means vigorous, full of life. The choice of the word is hardly coincidental though: not only does it yield a satisfying alliteration with 'leaves', but it also reminds us of the lust for life and repeatedly implied lustfulness of the young man. |

|

Beauty oresnowed and bareness everywhere.

|

The image is widened to the beauty of a summer landscape which now in winter is covered with snow, and everything looks barren and bare.

Most editors render Quarto's ore-snow'd as o'ersnowed. |

|

Then, were not summer's distillation left,

|

Then, in winter, if the beauty of summer were not kept in a distilled form, such as a perfume...

|

|

A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass,

|

...which is here described as a "liquid prisoner" that is kept in a glass vial or bottle: "walls of glass"... --

|

|

Beauty's effect with beauty were bereft

|

...if this distillation were not left behind, then the effect that beauty has on us or on the world – how it pleases us, makes us happy, gives us pleasure, enriches us – all this would disappear and die together with beauty itself when it dies.

|

|

Nor it nor no remembrance what it was.

|

Neither would beauty itself be left behind, nor anything to remind us of what it was.

For a contemporary English sentence, an 'of' is missing here, we would say: neither it nor any remembrance of what it was. |

|

But flowers distilled, though they with winter meet,

|

But flowers which have been distilled and turned into a perfume or fragrant water, even though they, like all flowers, will meet with and therefore die in winter...

|

|

Leese but their show, their substance still lives sweet.

|

...lose only their outward appearance and physical form – "leese but their show" – their essence lives on as a sweet or pleasant substance.

'Leese' means 'lose'. In other words: by distillation the beauty of summer, which we experience among others through its gorgeous flowers, can be preserved and its essence made to last until long after winter has effectively killed off summer. |

Sonnets 5 and 6 are the first in the series to come as a pair, and so while Sonnet 5 does make sense on its own, it really needs to be read in conjunction with Sonnet 6 for the argument to be properly made.

This, then, is the first half of a composition, and it lays out the premise, as it were. The premise is that time passes by the hour and this same phenomenon, time, that over many years has made you the beautiful human being that you are today will also ravage your beauty: as you grow older, your life turns from where it is now, in the full bloom of summer, to a cold and barren winter where your present beauty will have vanished.

In nature though, there is a remedy for this: we can distil the flowers of summer to preserve their essence. The sweet smell of the rose, for example, can be kept in rosewater, and so even though the flower itself will inescapably have to die, by allowing its petals to be distilled, it can keep something of itself alive.

What Shakespeare is building up to is of course more advice to the young man on what he should do, and it will come as no surprise that this is to effectively 'distil' his essence, by making a child.

Sonnet 5 on its own then does not tell us anything new, either about the Fair Youth or about Shakespeare, but it does tell us something very interesting about the time we find ourselves in: the seasons in Shakespeare's England are of fundamental, existential importance. Not only are people much more connected to nature generally and therefore no doubt also much more in tune with the weather and the seasons, but in an era before electricity, before central heating, and before modern clothing and construction materials, winters were long and cold and dark. Fuel and candles were expensive and even in a moderate climate like that of southern England and the Midlands, temperatures could be fierce. So for most people winter was really quite 'hideous', most of the time.

The beauty of a summer's day will find its expression and a great deal of meaning in one of Shakespeare's most famous sonnets soon, but first of all we will next find out how Shakespeare deploys his metaphor of the distilled perfume on the unsuspecting young man in Sonnet 6.

This, then, is the first half of a composition, and it lays out the premise, as it were. The premise is that time passes by the hour and this same phenomenon, time, that over many years has made you the beautiful human being that you are today will also ravage your beauty: as you grow older, your life turns from where it is now, in the full bloom of summer, to a cold and barren winter where your present beauty will have vanished.

In nature though, there is a remedy for this: we can distil the flowers of summer to preserve their essence. The sweet smell of the rose, for example, can be kept in rosewater, and so even though the flower itself will inescapably have to die, by allowing its petals to be distilled, it can keep something of itself alive.

What Shakespeare is building up to is of course more advice to the young man on what he should do, and it will come as no surprise that this is to effectively 'distil' his essence, by making a child.

Sonnet 5 on its own then does not tell us anything new, either about the Fair Youth or about Shakespeare, but it does tell us something very interesting about the time we find ourselves in: the seasons in Shakespeare's England are of fundamental, existential importance. Not only are people much more connected to nature generally and therefore no doubt also much more in tune with the weather and the seasons, but in an era before electricity, before central heating, and before modern clothing and construction materials, winters were long and cold and dark. Fuel and candles were expensive and even in a moderate climate like that of southern England and the Midlands, temperatures could be fierce. So for most people winter was really quite 'hideous', most of the time.

The beauty of a summer's day will find its expression and a great deal of meaning in one of Shakespeare's most famous sonnets soon, but first of all we will next find out how Shakespeare deploys his metaphor of the distilled perfume on the unsuspecting young man in Sonnet 6.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!