Sonnet 27: Weary With Toil, I Haste Me to My Bed

|

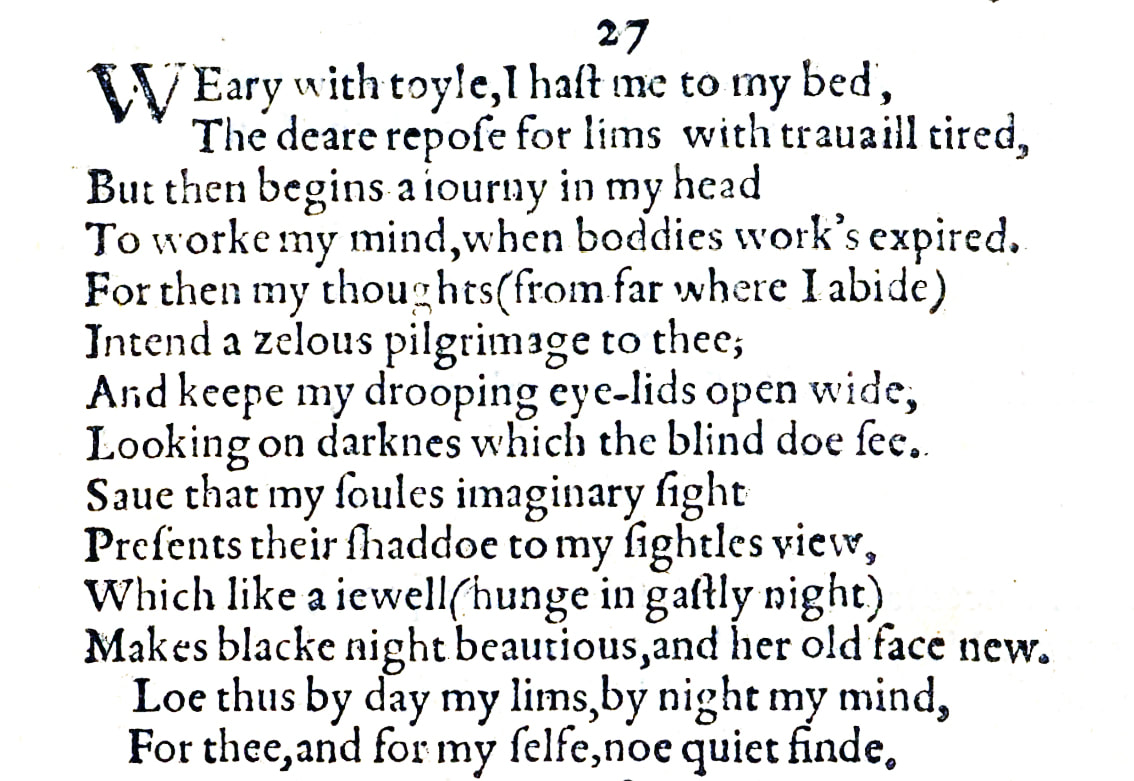

Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed,

The dear repose for limbs with travel tired, But then begins a journey in my head To work my mind when body's work's expired, For then my thoughts, from far where I abide, Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee, And keep my drooping eyelids open wide, Looking on darkness which the blind do see, Save that my soul's imaginary sight Presents thy shadow to my sightless view, Which like a jewel hung in ghastly night Makes black night beauteous and her old face new. Lo, thus by day my limbs, by night my mind For thee and for myself no quiet find. |

|

Weary with toil I haste me to my bed,

The dear repose for limbs with travel tired, |

Exhausted with the effort of my labours I hurry to bed, the cherished place of rest for my limbs which are tired with travel.

The word that Shakespeare actually uses here is 'travail' which can also be understood in the French sense – whence it stems – of 'work'. Most editors anglicise it to 'travel' here, because it is clear from the following lines that Shakespeare is talking about the exertions not only of his work – possibly here as a touring actor – but also of his journey, which at the time would have been carried out on horseback, often over long distances, and therefore been extremely tiring, as we shall see again before too long. |

|

But then begins a journey in my head

To work my mind when body's work's expired, |

But then, as soon as I have laid me down, a new journey starts, albeit one that takes place purely in my head and which therefore exercises my mind with work, at a time when the work of the body has been done. Or, put in more contemporary terms: now that my body can rest, my mind goes into overdrive.

|

|

For then my thoughts, from far where I abide,

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee, |

Because then my thoughts go on an eager journey of pilgrimage to you from here where I am, which is far away from you.

A pilgrimage is, of course, a religious undertaking, suggesting deep devotion and an undeterred commitment over long and arduous distance, and this sense of passion is underlined with the word 'zealous', which also has religious connotations, even though here it has a meaning of a more general keenness. |

|

And keep my drooping eyelids open wide,

Looking on darkness which the blind do see, |

And they, my thoughts, keep me awake with my eyes wide open staring at the darkness that surrounds me, which is as dark as what a blind person would see.

It is worth reminding ourselves here that we are talking about a night being spent in a country inn or at a market town guest house. There was, in rural England, virtually no light pollution, since there was no electricity, and so unless it was a clear night with a fairly full moon, lying in bed in your room could mean finding yourself in near pitch black: we can imagine this as really quite an intense darkness, of a deeper and much more oppressive kind than nowadays we are ever likely to experience or let alone are used to. |

|

Save that my soul's imaginary sight

Presents thy shadow to my sightless view, |

Except that my imagination puts a vision of you in front of my unseeing eyes.

This is not the only time in these sonnets that Shakespeare uses the word 'shadow' to mean an appearance that has no physical substance: an imagination or an internal vision. While we would associate 'shadow' with something dark, possibly even threatening, in Shakespeare's usage the word has a meaning more generally of a reflection or 'appearance'. The Quarto Edition here has: 'presents their shadow', but this is almost universally considered a typesetting error, as it simply doesn't make sense, whereas 'thy shadow' absolutely does, and also the words 'thy' and 'their' in handwriting may look very similar, so a mistake of this kind can easily be explained. |

|

Which, like a jewel hung in ghastly night,

Makes black night beauteous and her old face new. |

And this vision or apparition of you is like a jewel in the gloomy night, making her – the night – beautiful and young in appearance.

The idea here – as John Kerrigan in the New Penguin edition points out – stems from a belief at the time that some jewels emit a light of their own and therefore are like a lamp that can make the 'ghastly night' glow with a soft sheen. A jewel is also something that is worn by a person and can therefore serve to bring out their beautiful features. While the word 'ghastly' here has a less emphatic meaning than we today associate with it, and can thus be understood more in a sense of 'ominous', or even, in fact, 'ghostly' than our 'horrific', it does provide another indication of just how unappealing a dark night in Elizabethan England could be. |

|

Lo, thus by day my limbs, by night my mind

For thee and for myself no quiet find. |

And so it is that during the day my limbs, for which read my body, can find no rest, because I am working and/or travelling all day long, whereas by night it is my mind that can find no rest, because I stay awake thinking of you.

'Lo', sometimes furnished with an exclamation mark, simply means 'look' or 'behold' and serves to draw attention to something that is either noteworthy or surprising, such as this predicament the poet finds himself in. A slight difficulty for us arises from the last line, because we tend not to be used to Shakespearean levels of word play. He doubles the word 'for' and in doing so almost signals – perhaps a bit as a cryptic crossword setter would do today – that it also has a double meaning. Firstly, and obviously: I can not find any rest for myself, as in: I deprive myself of rest through my work during the day and through my thinking of you in the night; and secondly, because I think of you, I can find no rest, as in: it is for you – on account of my thinking of you – that I can find no rest. The use of 'for' to mean 'because' is, of course, extremely common in poetic language, in Shakespeare and far beyond. |

Sonnet 27 is the first of several sonnets in which Shakespeare laments the fact that he is away from his young lover, thus answering the question posed indirectly by Sonnet 26 as to who is on the move. And while this sonnet can stand on its own, with a fully formed and perfectly concluded argument, it does come as a pair with Sonnet 28, which follows on directly from it and which, by contrast, relies on this sonnet to be properly introduced. The two should therefore be looked at together, and we will do so when we get to Sonnet 28.

Sonnet 27 yields a fascinating insight into Shakespeare's reality beyond his relationship with the young man. It is clear from this poem that he is travelling and that his journey is taking him some distance away from where the young man is. Much as we can't say with any certainty who the young man is, so we also can only speculate about the geographical constellation, but what makes most sense and is therefore a perfectly plausible starting point is that we are talking about London and that therefore this sonnet stems from one of what appear to be several occasions when Shakespeare is 'on the road' away from London.

This tallies entirely and exactly with what we know about Shakespeare's work as an actor, writer and shareholder with The Lord Chamberlain's Men and with outbreaks of the plague in London. London had seen a serious outbreak of the plague back in 1563 – a year or so before Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon – and a much more devastating one came in the autumn of 1592, lasting throughout 1593 until May 1594. During much of this time, London theatres were forced to close to prevent the spread of the deadly disease, and so it is highly likely that Shakespeare and his troupe of actors did what came naturally: leave town and go on tour.

Touring in Shakespeare's day is not an easy, comfortable, or roundly enjoyable job, and so it comes as no surprise that the words 'travel' and 'travail', and indeed 'toil' are used more or less interchangeably: you had to load your costumes and props and instruments, and any pieces you might use for a stage or a set, onto carts and you travelled on horseback yourself, or possibly in a simple horse-drawn carriage. You were exposed to the elements, your roads were bumpy and marked with potholes. The places you stayed at in the majority were inns and pubs or guesthouses with little by way of comfort. Actors enjoyed few privileges and low status. Even though a troupe of actors like The Lord Chamberlain's Men had a powerful patron – and they were, ultimately, to become the King's Men and thus enjoy the patronage of the most powerful person in the country – and even though they provided much loved theatre to tens of thousands of people, they were not held in very high regard socially and so received few luxuries.

While all of this is interesting to note in itself and gives us a flavour of Shakespeare's life, it also offers yet another potentially significant pointer towards the dating of this sequence of the sonnets, which in turn – as we know – helps us form an idea of who the young recipient might be.

There is no proof that Shakespeare went on tour with his own theatre company during the plague in London but it is, for obvious reasons, considered highly likely. Similarly, there is no reason why Shakespeare couldn't or shouldn't be travelling at times other than during the plague in London. In fact, we know that he went back to Stratford-upon-Avon on a quite regular basis. That said, this sonnet and its companion Sonnet 28 really do not sound like the kind of poetry a man is writing who is visiting home where he has a wife and three children. Nor does it sound like the kind of poetry a man is writing who is just visiting friends in the country. It sounds very much like the kind of poetry a man is writing who is travelling because he has to and whose journey is wearing him out. What corroborates this notion is that there will shortly be further poems very much in a similar vein, and this in turn supports the idea we are forming that William Shakespeare, by the time he gets to writing these sonnets to or for his young man, is away from London for extended and possibly repeated periods. The outbreaks of the plague in London of between autumn 1592 and early summer 1594 give us a perfect reason for this to be necessary and so likely as to be highly probable.

It also is of course this precisely the period we identified as the first really likely phase during which these sonnets could have been written, and that would once more rather favour one particular candidate for the Fair Youth. But staying with the principle of listening to what the words tell us and taking things step by step as we piece together a picture of a plausible background to these sonnets, let us not at this point veer off into a discussion about the Fair Youth, but note the actually very straightforward and easy-to-process factuality this sonnet, together with the one that follows, suggests, which – apart from the uncomfortable journeying and longing for the one who's left behind – is one thing more than any other: the factuality itself.

We are, of course, absolutely and entirely in the format of the sonnet here, but the subject matter, the tone, the expression of what is happening is as directly personal and relatable to real-life events as they can be: there is really no reason why anybody who is just sonneteering for the sake or even for the love of it would invent an arduous trip to then bemoan the fact that he's away in this manner. These two Sonnets 27 and 28 do not prove anything, but they come as close as we can wish to putting paid to the idea that Shakespeare may here be simply exercising his craft.

Sonnet 27 is effectively a letter to my loved one saying: I am exhausted and I miss you. Whether or not Shakespeare sent this sonnet – as he says he sent Sonnet 26, to be a 'written embassage' – we do not know, but what we do know is that all these poems, Sonnets 26, 27, 28 and the majestic Sonnet 29, as well as the one that follows and echos it Sonnet 30, make up a coherent sequence of communication that has at its heart a dejected absence, redeemed and alleviated only by the faith in, hope for, thought of, and love for the young man.

These sonnets are profoundly moving because they are so profoundly and viscerally felt. They are anything but sweetly romantic, they are a lived and suffered and sustained experience. Which is what makes them so extraordinary and so extraordinarily revealing and so undeniably specific and personal. And this sense of absence and longing and prevailing despair continues to be expressed in Sonnet 28...

Sonnet 27 yields a fascinating insight into Shakespeare's reality beyond his relationship with the young man. It is clear from this poem that he is travelling and that his journey is taking him some distance away from where the young man is. Much as we can't say with any certainty who the young man is, so we also can only speculate about the geographical constellation, but what makes most sense and is therefore a perfectly plausible starting point is that we are talking about London and that therefore this sonnet stems from one of what appear to be several occasions when Shakespeare is 'on the road' away from London.

This tallies entirely and exactly with what we know about Shakespeare's work as an actor, writer and shareholder with The Lord Chamberlain's Men and with outbreaks of the plague in London. London had seen a serious outbreak of the plague back in 1563 – a year or so before Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon – and a much more devastating one came in the autumn of 1592, lasting throughout 1593 until May 1594. During much of this time, London theatres were forced to close to prevent the spread of the deadly disease, and so it is highly likely that Shakespeare and his troupe of actors did what came naturally: leave town and go on tour.

Touring in Shakespeare's day is not an easy, comfortable, or roundly enjoyable job, and so it comes as no surprise that the words 'travel' and 'travail', and indeed 'toil' are used more or less interchangeably: you had to load your costumes and props and instruments, and any pieces you might use for a stage or a set, onto carts and you travelled on horseback yourself, or possibly in a simple horse-drawn carriage. You were exposed to the elements, your roads were bumpy and marked with potholes. The places you stayed at in the majority were inns and pubs or guesthouses with little by way of comfort. Actors enjoyed few privileges and low status. Even though a troupe of actors like The Lord Chamberlain's Men had a powerful patron – and they were, ultimately, to become the King's Men and thus enjoy the patronage of the most powerful person in the country – and even though they provided much loved theatre to tens of thousands of people, they were not held in very high regard socially and so received few luxuries.

While all of this is interesting to note in itself and gives us a flavour of Shakespeare's life, it also offers yet another potentially significant pointer towards the dating of this sequence of the sonnets, which in turn – as we know – helps us form an idea of who the young recipient might be.

There is no proof that Shakespeare went on tour with his own theatre company during the plague in London but it is, for obvious reasons, considered highly likely. Similarly, there is no reason why Shakespeare couldn't or shouldn't be travelling at times other than during the plague in London. In fact, we know that he went back to Stratford-upon-Avon on a quite regular basis. That said, this sonnet and its companion Sonnet 28 really do not sound like the kind of poetry a man is writing who is visiting home where he has a wife and three children. Nor does it sound like the kind of poetry a man is writing who is just visiting friends in the country. It sounds very much like the kind of poetry a man is writing who is travelling because he has to and whose journey is wearing him out. What corroborates this notion is that there will shortly be further poems very much in a similar vein, and this in turn supports the idea we are forming that William Shakespeare, by the time he gets to writing these sonnets to or for his young man, is away from London for extended and possibly repeated periods. The outbreaks of the plague in London of between autumn 1592 and early summer 1594 give us a perfect reason for this to be necessary and so likely as to be highly probable.

It also is of course this precisely the period we identified as the first really likely phase during which these sonnets could have been written, and that would once more rather favour one particular candidate for the Fair Youth. But staying with the principle of listening to what the words tell us and taking things step by step as we piece together a picture of a plausible background to these sonnets, let us not at this point veer off into a discussion about the Fair Youth, but note the actually very straightforward and easy-to-process factuality this sonnet, together with the one that follows, suggests, which – apart from the uncomfortable journeying and longing for the one who's left behind – is one thing more than any other: the factuality itself.

We are, of course, absolutely and entirely in the format of the sonnet here, but the subject matter, the tone, the expression of what is happening is as directly personal and relatable to real-life events as they can be: there is really no reason why anybody who is just sonneteering for the sake or even for the love of it would invent an arduous trip to then bemoan the fact that he's away in this manner. These two Sonnets 27 and 28 do not prove anything, but they come as close as we can wish to putting paid to the idea that Shakespeare may here be simply exercising his craft.

Sonnet 27 is effectively a letter to my loved one saying: I am exhausted and I miss you. Whether or not Shakespeare sent this sonnet – as he says he sent Sonnet 26, to be a 'written embassage' – we do not know, but what we do know is that all these poems, Sonnets 26, 27, 28 and the majestic Sonnet 29, as well as the one that follows and echos it Sonnet 30, make up a coherent sequence of communication that has at its heart a dejected absence, redeemed and alleviated only by the faith in, hope for, thought of, and love for the young man.

These sonnets are profoundly moving because they are so profoundly and viscerally felt. They are anything but sweetly romantic, they are a lived and suffered and sustained experience. Which is what makes them so extraordinary and so extraordinarily revealing and so undeniably specific and personal. And this sense of absence and longing and prevailing despair continues to be expressed in Sonnet 28...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!