Sonnet 32: If Thou Survive My Well-Contented Day

|

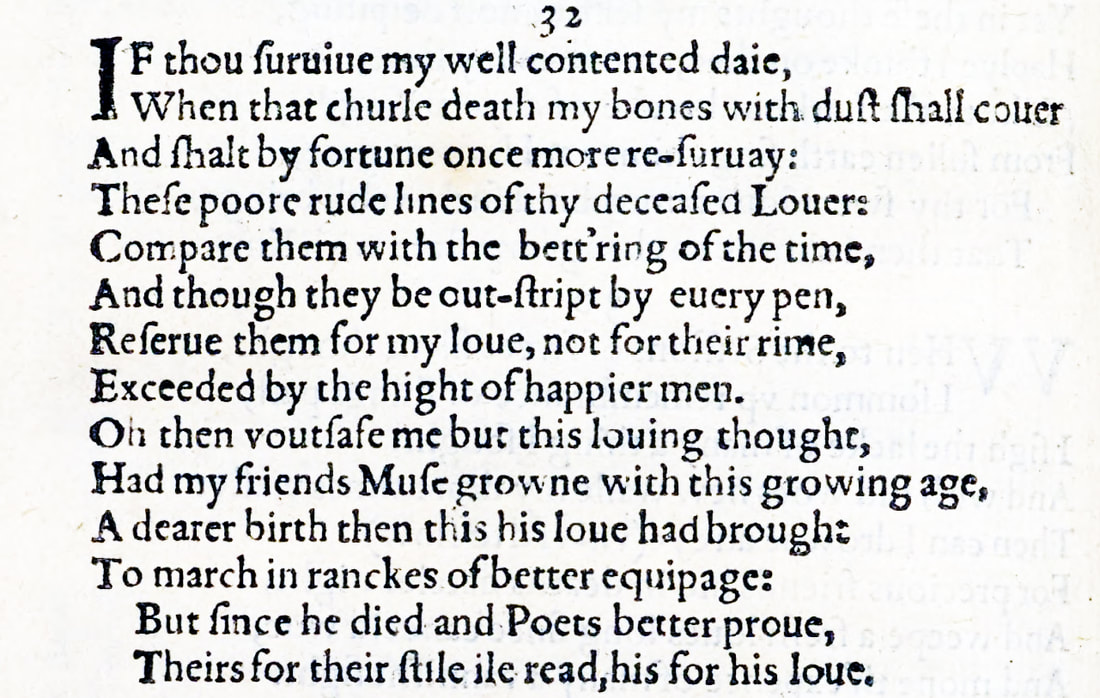

If thou survive my well-contented day,

When that churl death my bones with dust shall cover, And shalt by fortune once more resurvey These poor, rude lines of thy deceased lover, Compare them with the bettering of the time, And though they be outstripped by every pen, Reserve them for my love, not for their rhyme, Exceeded by the height of happier men. O then vouchsafe me but this loving thought: Had my friend's muse grown with this growing age, A dearer birth than this his love had brought, To march in ranks of better equipage. But since he died and poets better prove, Theirs for their style I'll read, his for his love. |

|

If thou survive my well-contented day,

|

If you outlive me...

The 'well-contented day' is the day when life is fulfilled and therefore content both in terms of what it requires and also in terms of how it all will have panned out: Shakespeare is striking an easy, satisfied note by anticipating that he will die a man who has done what he needed to do and will therefore be ready to go. And although this sonnet makes no direct reference to Sonnet 30, it is nevertheless striking how the sense of loss, regret, and dissatisfaction of only two sonnets ago has given way to a fairly stoic acceptance of the eventual termination of life. The prospect of being outlived by the young man, meanwhile, is a reasonable one, since – as we have seen – there must be at least about ten years' age difference between them. |

|

When that churl death my bones with dust shall cover,

|

...when I am laid into my grave...

The fairly light, so as not to say humorous tone continues. Death – in other poems taken to be and described as much more menacing – is here a 'churl', a 'rude and mean-spirited person', as the dictionary has it; or simply, at the time, a peasant: a roughneck, uneducated character who now that I am dead is going to cover my bones with dust. The image of death as an uncouth character shovelling dust over the bones of the deceased poet is both stark and slightly surreal. In the traditional, and also biblical, understanding, we ourselves, through death, turn back to dust, or rather our bodies do, whilst our souls move on to the afterlife. This deviation from the norm points at something of a caricature. |

|

And shalt by fortune once more resurvey

These poor, rude lines of thy deceased lover, |

...and it should so happen at that time that you come across these badly written verses of mine, your deceased lover...

The casual tone continues: I, the poet, imagine my young lover going through his papers or books or letters and finding these poems which I myself describe as 'poor' and 'rude'. 'Rude' here has a meaning more or 'rough', 'unskilled', or technically 'coarse', without necessarily wanting to suggest innuendo or sexual overtones, or in some way insulting content. In A Midsummer Night's Dream, Puck, the servant spirit to the fairy king Oberon, refers to the craftsmen who go to the forest to rehearse their play, as "rude mechanicals," again without really implying that there is anything overtly rude about them in our sense today, but more simply suggesting that they are unschooled and therefore unskilled in the art of playmaking and acting. This, as it happens, turns out to be the case, to much hilarity... Noteworthy is that Shakespeare here directly and unambiguously refers to himself as the young man's 'lover'. Although this in itself does not mean that the two are now in a physical relationship, the previous sonnet seems to suggest as much and the appearance here of this word in such an unabashed manner would support that impression. There is of course – and this may not be a bad moment to point this out – in antiquity and therefore to quite some extent in the Renaissance, a distinction being made between the 'lover' and the 'beloved' in male erotic or sexual relationships, whereby usually the 'lover' is the older man and the 'beloved' the younger. Whether or not Shakespeare means to allude to this here we absolutely can't say. It seems likely that he would have known about these terms, but the power dynamic between the two is entirely not that of a classical male relationship, since here the young man almost certainly is someone who is much richer, much more influential, and of signally higher social status than William Shakespeare. Which is also the reason, should you have wondered, why throughout this podcast I have been referring to the young man as Shakespeare's 'lover' rather than as his 'beloved', since we really don't know all that much about the internal workings of their relationship, let alone about the nature of their physical contact – if any – at this time. |

|

Compare them with the bettering of the time,

|

...look at them in the context of a world that is ever-improving and growing...

Here it is worth bearing in mind that we find ourselves right at the apex of the English Renaissance, and so if Shakespeare and at least some of his contemporaries felt that their times were fast-developing, there is good reason for this. Art, literature, the beginnings of science, and philosophy are all propelling the human race forward in unprecedented ways at this time, so it is certainly one that is continuously 'bettering' itself on an almost daily basis. Note that 'bettering' – as in fact spelt in the Quarto Edition – needs to be pronounced as two syllables: bett'ring. |

|

And though they be outstripped by every pen,

|

...and although these verses will be outstripped or outdone not just by some, but by every writer who is to follow...

Shakespeare is laying it on a bit here: elsewhere, he most famously and memorably tells the young man that he will live in these verses forever, and so indeed the whole tonality of this sonnet is more than jut a tad tongue in cheek. |

|

Reserve them for my love, not for their rhyme,

Exceeded by the height of happier men. |

...and keep these verses for the sake of my love, not for the quality of the writing, which will by then have been exceeded by the high levels of artistry and writerly skill of men who are better favoured by fortune than me.

This echoes Sonnets 25 and 29, in which I lamented the fact – or at any rate my perception – that I am not 'in favour' with the 'stars', but find myself to be 'in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes' respectively. And this happiness of other men here alluded to surely needs to be seen in this context: William Shakespeare does not consider himself to be professionally lucky or successful and here makes a big – some might say disingenuously enormous – deal of his own poor abilities. |

|

O then vouchsafe me but this loving thought:

|

O then grant me just this one loving thought:

The use of the word 'vouchsafe' continues to underline the hyperbolic and therefore slightly humorous tone: it means to 'grant graciously' or indeed even 'in a condescending manner', and the way Shakespeare formulates this loving thought now does this note of condescension full justice, because it goes: |

|

Had my friend's muse grown with this growing age

|

If the skill and inspiration of my friend had grown at the same pace as the one the age we live in develops...

|

|

A dearer birth than this his love had brought

|

...then his love would have prompted him to produce a 'dearer birth' than this...

'Dearer birth' is such a gloriously patronising term that I scarcely dare explain it, as it can only ever lose in translation: it means of course a better poem, but coaches this in the figure of a child having being born, and not a particularly lovable one at that. A dearer birth would be a poetic offspring that could be loved more easily. |

|

To march in ranks of better equipage.

|

...and such a poem would therefore then, on account of being altogether better, be allowed to join the ranks of far superior poetry.

'Equipage' really is defined as 'equipment for a particular purpose', but in the context of it marching in 'ranks', the metaphor is clearly a military one. |

|

But since he died and poets better prove

|

But since he – my friend, the poet – died and today's poets are obviously better than he ever was...

|

|

Theirs for their style I'll read, his for his love.

|

...I will read their work for the quality of their writing and their advanced style, while reading his purely for his love. Which is exactly what the friend, poet, and lover, William Shakespeare, suggested he do at the end of the second quatrain.

|

The wryly ironic Sonnet 32 marks a caesura in the canon, as it sits right between a development arc in the relationship that spans the sequence uninterrupted from Sonnet 18 to Sonnet 31, while giving nothing away of the entirely new phase the relationship enters with the storm clouds that gather in Sonnet 33. In tone, in attitude, in self-evaluation, it gains access to a register different to any that has gone before and quite unlike any that is soon to come, and so it stands out, rather, for being really quite unique.

Sonnet 32 is not the first sonnet in which Shakespeare belittles his own writing, in stark contrast to the ones where he predicts with by our standards breathtaking confidence – but correctly – that his poetry will live forever. In Sonnet 16, having almost teased the young man with an innuendo-laden play on words and invoked a startlingly visceral image by saying about Time that

As he takes from you, I engraft you new

Shakespeare then backed down with some haste, offering the not altogether indisingenuous question:

But wherefore do not you a mightier way

Make war upon this bloody tyrant Time

And fortify yourself in your decay

With means more blessed than my barren rhyme?

Follow this, a few lines later, by describing his writing as a 'pupil pen'. We found it fascinating to note this at the time and wondered whether both the use of the more formal 'you' in those two sonnets as well as the near-humorous downplaying of his own powers as a writer were meant to signal to the young man that Shakespeare knows his place in the world. It's not a question we were able to answer conclusively then, and similarly we can now only guess at what brings on this change of tone.

This poem, Sonnet 32, is certainly confident. It purports to be self-effacing, but we find it hard to take 'poor, rude lines' entirely seriously, any more than 'barren rhyme.' And yet, the confidence, such as it is, seems to stem not from the poet's faith in his own poetry, which he in a sense mocks, but from his position in relation to the young man. Because while some of the previous sonnets have drawn this seriously into question, Sonnet 32, when it comes to the relationship status, is wholly sure of itself. I, the poet, William Shakespeare am, in this anticipated scenario in the future, your 'deceased lover'. And my day is 'well-contented': I die a happy man, so long as I know that you will remember me fondly for my love, even if you don't rate my poetry so highly.

And this, after everything that has gone before, invites us to revisit the question: what does Shakespeare receive back in terms of communication from the young man between sonnets? Does he receive back anything at all? Does the young man get to read these sonnets, each before the next one is written? We don't know, but it looks very much like it, and it would make sense. The more we read these sonnets, the more they appear to be one side of a communication. We received this impression before, and in Sonnet 26 we had it spelt out by Shakespeare that he was sending that sonnet as a written embassage. We've heard Shakespeare explain how he gets tongue-tied in Sonnet 23, and we now have this marked contrast between Shakespeare's sense of who he is in relation to the young man, and how his writing is perceived. And as has happened once before, we get the impression that maybe the young man has not been altogether complimentary about Shakespeare's sonnets. But here Shakespeare does not take offence, nor does he in that sense plead; he seems to slightly mock also the young man, by making him 'vouchsafe' him 'just this loving thought'.

To be sure, we are here in the realm of supposition, what elsewhere I have called and generally like to think of as conjecture. But it is a curious sonnet this that – although it holds such a unique position – actually fits the sequence remarkably well. If our impression with Sonnet 31 was right, and the relationship has moved onto a different plateau, one on which Shakespeare feels confident to drop strong hints at a physical, maybe sexual expression and where certainly he was happy to describe himself as the young man's lover, here this confidence, for which the English language has the to us ever so slightly crude sounding term cocksure, is still present too. Today I am your lover, in the future I will be your deceased lover, but lover I will be. And it goes right hand in hand with this notion we receive that I am also teasing you, the young man, for having been under-appreciative or possibly even disparaging about my poetry; Oh, if only I were a better poet then my muse should be able to bring forth a 'dearer birth than this'.

What this Sonnet 32 does is show us Shakespeare having a good time. And quite possibly the good time that was suggested by Sonnet 31. This sonnet sounds like a confident lover taking his leave from the man he has spent a night with, and doing so with a salvo. And can it be a coincidence or a fluke that he quits the metaphorical room of this poem with the word 'love'?

We cannot know what reasons Shakespeare has for feeling that he has the love of the young man. But what we can be as good as certain of is that he feels he does. And just as once before when that was the case and Shakespeare felt sure of himself with his young man, the young man then went and took him down a peg or two, so here, what is about to happen will put everything into yet another, whole new light and tell us a great deal indeed about the complex love lives of William Shakespeare and his young lover...

Sonnet 32 is not the first sonnet in which Shakespeare belittles his own writing, in stark contrast to the ones where he predicts with by our standards breathtaking confidence – but correctly – that his poetry will live forever. In Sonnet 16, having almost teased the young man with an innuendo-laden play on words and invoked a startlingly visceral image by saying about Time that

As he takes from you, I engraft you new

Shakespeare then backed down with some haste, offering the not altogether indisingenuous question:

But wherefore do not you a mightier way

Make war upon this bloody tyrant Time

And fortify yourself in your decay

With means more blessed than my barren rhyme?

Follow this, a few lines later, by describing his writing as a 'pupil pen'. We found it fascinating to note this at the time and wondered whether both the use of the more formal 'you' in those two sonnets as well as the near-humorous downplaying of his own powers as a writer were meant to signal to the young man that Shakespeare knows his place in the world. It's not a question we were able to answer conclusively then, and similarly we can now only guess at what brings on this change of tone.

This poem, Sonnet 32, is certainly confident. It purports to be self-effacing, but we find it hard to take 'poor, rude lines' entirely seriously, any more than 'barren rhyme.' And yet, the confidence, such as it is, seems to stem not from the poet's faith in his own poetry, which he in a sense mocks, but from his position in relation to the young man. Because while some of the previous sonnets have drawn this seriously into question, Sonnet 32, when it comes to the relationship status, is wholly sure of itself. I, the poet, William Shakespeare am, in this anticipated scenario in the future, your 'deceased lover'. And my day is 'well-contented': I die a happy man, so long as I know that you will remember me fondly for my love, even if you don't rate my poetry so highly.

And this, after everything that has gone before, invites us to revisit the question: what does Shakespeare receive back in terms of communication from the young man between sonnets? Does he receive back anything at all? Does the young man get to read these sonnets, each before the next one is written? We don't know, but it looks very much like it, and it would make sense. The more we read these sonnets, the more they appear to be one side of a communication. We received this impression before, and in Sonnet 26 we had it spelt out by Shakespeare that he was sending that sonnet as a written embassage. We've heard Shakespeare explain how he gets tongue-tied in Sonnet 23, and we now have this marked contrast between Shakespeare's sense of who he is in relation to the young man, and how his writing is perceived. And as has happened once before, we get the impression that maybe the young man has not been altogether complimentary about Shakespeare's sonnets. But here Shakespeare does not take offence, nor does he in that sense plead; he seems to slightly mock also the young man, by making him 'vouchsafe' him 'just this loving thought'.

To be sure, we are here in the realm of supposition, what elsewhere I have called and generally like to think of as conjecture. But it is a curious sonnet this that – although it holds such a unique position – actually fits the sequence remarkably well. If our impression with Sonnet 31 was right, and the relationship has moved onto a different plateau, one on which Shakespeare feels confident to drop strong hints at a physical, maybe sexual expression and where certainly he was happy to describe himself as the young man's lover, here this confidence, for which the English language has the to us ever so slightly crude sounding term cocksure, is still present too. Today I am your lover, in the future I will be your deceased lover, but lover I will be. And it goes right hand in hand with this notion we receive that I am also teasing you, the young man, for having been under-appreciative or possibly even disparaging about my poetry; Oh, if only I were a better poet then my muse should be able to bring forth a 'dearer birth than this'.

What this Sonnet 32 does is show us Shakespeare having a good time. And quite possibly the good time that was suggested by Sonnet 31. This sonnet sounds like a confident lover taking his leave from the man he has spent a night with, and doing so with a salvo. And can it be a coincidence or a fluke that he quits the metaphorical room of this poem with the word 'love'?

We cannot know what reasons Shakespeare has for feeling that he has the love of the young man. But what we can be as good as certain of is that he feels he does. And just as once before when that was the case and Shakespeare felt sure of himself with his young man, the young man then went and took him down a peg or two, so here, what is about to happen will put everything into yet another, whole new light and tell us a great deal indeed about the complex love lives of William Shakespeare and his young lover...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!