Sonnet 36: Let Me Confess That We Two Must Be Twain

|

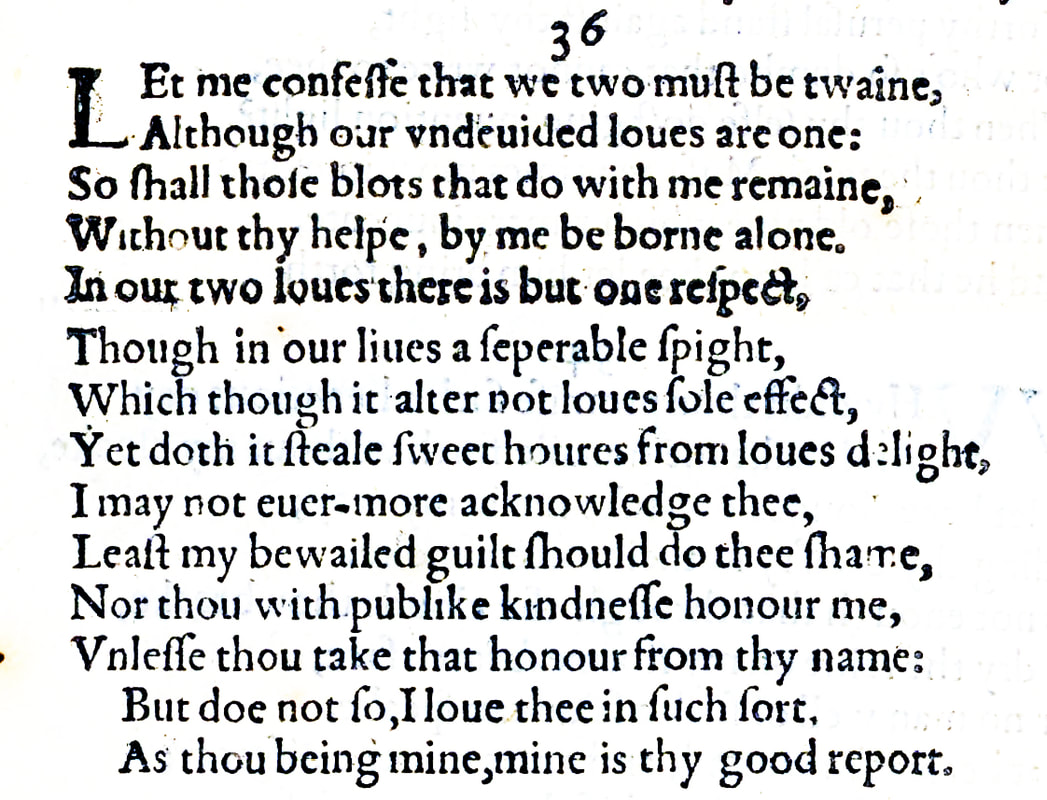

Let me confess that we two must be twain,

Although our undivided loves are one; So shall those blots that do with me remain Without thy help by me be borne alone. In our two loves there is but one respect, Though in our lives a separable spite, Which, though it alter not love's sole effect, Yet doth it steal sweet hours from love's delight. I may not evermore acknowledge thee, Lest my bewailed guilt should do thee shame, Nor thou with public kindness honour me, Unless thou take that honour from thy name. But do not so, I love thee in such sort As thou being mine, mine is thy good report. |

|

Let me confess that we two must be twain

Although our undivided loves are one, |

Let me admit that we have to be apart, even though we are undivided and in our love as one.

|

|

So shall those blots that do with me remain

Without thy help by me be borne alone. |

This way those moral stains on my reputation which result from my own faults or sins that I have committed will stay with me and will not tarnish you, and I will bear them and deal with them alone, without your help.

What these sins are or might be we don't know and the sonnet doesn't say, but what is most intriguing is that they are cited here so hard on the heels of the young man's blatant and strongly suggested faults and sins of the previous three sonnets. |

|

In our two loves there is but one respect

|

Our two loves only have one mutual regard, namely mine to you and yours to me, or possibly, also we two are one and so we both look in the same direction and see things the same...

|

|

Though in our lives a separable spite

|

...but in our lives there is an element or a force that spitefully – which implies a deliberate maliciousness – aims to separate us.

|

|

Which, though it alter not love's sole effect,

Yet doth it steal sweet hours from love's delight. |

...and this force, although it cannot change the singular effect that our love for each other has on us, it still takes away our ability to spend delightful hours together and enjoy each other's love.

|

|

I may not ever more acknowledge thee

Lest my bewailed guilt should do thee shame, |

I may not acknowledge you in public any more or associate with you, or see you, because if I were to do so then this guilt of mine, which causes me such grief, would tarnish your own reputation.

|

|

Nor thou with public kindness honour me,

Unless thou take that honour from thy name. |

Nor should you show me any kindness in public and in doing so honour me, because if you do so you will dishonour yourself.

|

|

But do not so: I love thee in such sort

As thou being mine, mine is thy good report. |

But do not do this, do not dishonour yourself in this way, because my love for you is such that since you are mine, your good reputation is therefore also mine, in other words: if you look after your good name and standing in the world, then because of the love I bear you and because I consider you a part of me, I am then sufficed and content and, importantly, I consider my standing in the world to be intact.

The same couplet also closes Sonnet 96, but when here it makes perfect sense, there, as we shall see when we get to it, it really doesn't, which may simply mean that it slipped in there by mistake. |

With the curious Sonnet 36 William Shakespeare appears to be either inverting the guilt and shame that the previous three sonnets have laid upon the young man for his evident transgression and projecting it directly on himself, or to be uncovering a new source of scandal that gives him reason to suggest – borderline disingenuously, it might seem – that they dissociate themselves from each other, even though in the same breath it also emphatically confirms the love they hold for each other.

After everything that has happened – or, to be more precise, that is reflected as having happened – in the last three sonnets, Sonnet 36 comes as something of a surprise. And here, before delving into its possible significance in the sequence, it may be prudent to remind ourselves that the sequence may in fact be corrupt. This is the first time this really suggests itself – and it does so as a partial explanation for the radical change of perception in who is at fault, because up until now we have not seen any reason to question the order of events. With Sonnet 36 though, a tentative question mark arises. Then again, we also have made ourselves aware some time ago that we do not know what happens in-between sonnets. Neither do we know how much time passes, nor do we know what, if anything, the young man says or writes in response to reading or hearing these sonnets, if he reads or hears them at all.

All that said as a general caveat, Sonnet 36 breaks fascinating new ground. It states quite categorically two 'facts', or at any rate perceived facts, that stand at odds with each other: one, we two are one; two, we two must be apart. Having just admonished the young man for having done wrong, it now speaks of the "blots that do with me remain," without expounding what these blots are, and so we do not know whether William Shakespeare is taking the notion of two lovers being one to its ultimate consequence by saying you have done me wrong by – as we saw in the previous sonnet – clearly committing some sexual misdeed and because we are one the stain that this causes on your reputation is now also on me, and so therefore to protect you I shall bear this blot without you by myself so that your standing in society is not further threatened, or is William Shakespeare taking what has just happened as his opportunity to load blame and contrition upon himself for what he has done himself with and in relation to other people, such as, perhaps the person whom the young man seems to have 'stolen' from him. Either are possible, as is a combination of the two.

Sonnet 36 gives no answers to this question: all it says, with a great deal of conviction, is that this shame or dishonour that is now upon me is something I shall have to bear by myself, I will protect you as best I can from being dragged down with me, and, significantly, this calamity does not stem from anything you or I have done in relation to each other, because "our undivided loves are one." This thing that we are talking about is caused by a "separable spite" in our lives, in other words: an external factor that is not purely coincidental but that appears to have some malign intent against us.

Sonnets 40, 41, and then particularly 42 will give us a great deal more insight into what is likely to have been the cause for the crisis that triggered the previous three sonnets, and it is entirely possible, though not certain, that this Sonnet 36 also attempts to deal with the same situation.

And here is where, exceptionally, we may do well to avail ourselves of one of the rare external sources to lend a bit of tantalising context. Again, it behoves me to urge caution and to emphasise that we cannot know whether this reference here applies or not, all we can say is that it exists, and that it could well match up. And the best reason we have for even introducing it here is simply that the sonnet on its own poses such an odd proposition that in itself seems to beg for a bit of context.

In September 1594, a writer named Henry Willobie published in pamphlet format a narrative poem entitled Willobie His Avisa. It would go way too far to enter in on any detail about this piece which was not then and is not now held in high literary regard. But this did not stop it from being exceptionally popular, allowing it to go into several reprints, even though – or quite possibly because – it was also censored and banned for a while, five years after its initial publication.

The piece is interesting because it talks of a W. S. and his close or, as its author puts it, 'familiar' friend H. W. who share "the curtesy" of a "like passion" for a lady, resulting in a "like infection." The initials H. W. of course are compatible with Henry Willobie, but although a Henry Willobie existed, some people doubt that he actually wrote this. H. W. certainly though are also the initials of Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, and while nobody seriously believes he wrote the pamphlet, he is one of the strongest candidates for the Fair Youth and thus the person whom all of these sonnets so far are addressed to or about, as we discussed a little while ago and will examine in a great deal more detail in episodes to come.

Without wishing to read too much into any of this, and whether any of it is based in actual fact, in mere gossip, or some person's fertile imagination, this much we can say: in September 1594, at a time when the relationship between William Shakespeare and the young man may well be established enough for it to entail all the components we have come across thus far, and when Shakespeare would have had reason and opportunity to leave London because of the plague and also return to be reunited with his lover; at a time when he would now have turned thirty and the most likely candidate for his young lover within this time frame would be approaching 20, somebody publishes a piece of print that is so full of coded references, allusions, and nudging innuendo that the general public lap it up even though it isn't very good, the authorities ban it until after the death of Queen Elizabeth I, and one of the central constellations in it appears to mirror to some extent the events in the sonnets that could absolutely have been written around that time. That is all we know.

We don't know whether the person who wrote Willobie His Avisa was deliberately referencing the Queen herself or her court or people around her court when he made the maid protagonist of his poem, Avisa, sign her letters with the words "always the same," which just happens to be a direct English translation of the Queen's motto semper eadem, We don't know whether he meant to implicate William Shakespeare with his W. S. character, let alone Henry Wriothesley with his young but familiar friend H. W., and we don't know exactly what the implication is of the claim contained in the publication that “there is some thing under these false names and showes that hath been done truly.”

What we do know is that if such a pamphlet was published at a time when our Will and his young man were undergoing a relationship crisis caused by the young man 'stealing' or 'robbing' – as Sonnet 35 strongly suggests – a person whom William Shakespeare considered to be his, then this would, in London at the time, be widely known and talked about, and if it involved, as it may well have done and as so far we have been led to believe, a notable, extremely well-connected young nobleman, this would heighten the stakes considerably. If the two people thus satirised are indeed William Shakespeare and Henry Wriothesley, who, after all was brought up as the ward of Lord Burleigh, chief advisor to the Queen, then the situation could potentially be explosive. And so this "separable spite" that has burrowed itself into the union between these two men may suddenly be exceptionally real. The young man getting off with someone is one thing. The young man getting off with my own lover, affair, bit on the side, mistress, is quite another. Any of this being made public, or as near as public as anyone would dare, even though it be in coded language: that is a scandal in the most applicable sense. The town would be talking about this, the young man's reputation would be severely threatened, the Queen herself may be incensed. And that is not a fire you want to play with...

We have swerved and departed unusually far from the words themselves. The words of this Sonnet 36 make no mention of Willobie, of Avisa, of the Queen. They don't directly refer to the young man's transgression and they certainly don't give us a date to plot on the timeline. What they do give us is an indication that if I am William Shakespeare and you are a young English nobleman of some considerable note, then no matter how much we two love each other, there is a world out there, and this world is not all accepting, embracing, and benign. There are adverse factors out there, and some of these factors may well be just people who, for whatever reason – be it envy, be it disapproval, be it arrogance or ignorance – and given the chance, would come between us.

Sonnet 36 seems to stand on its own in this acute awareness of what other people think or say about us. And for quite a while it does. This tone, and this conscious reflection on the outside world does not reappear for another thirty-odd sonnets. Before then though, we will get many twists and turns and many profound reflections from Shakespeare on life, and time, and death, and beauty, and love.

After everything that has happened – or, to be more precise, that is reflected as having happened – in the last three sonnets, Sonnet 36 comes as something of a surprise. And here, before delving into its possible significance in the sequence, it may be prudent to remind ourselves that the sequence may in fact be corrupt. This is the first time this really suggests itself – and it does so as a partial explanation for the radical change of perception in who is at fault, because up until now we have not seen any reason to question the order of events. With Sonnet 36 though, a tentative question mark arises. Then again, we also have made ourselves aware some time ago that we do not know what happens in-between sonnets. Neither do we know how much time passes, nor do we know what, if anything, the young man says or writes in response to reading or hearing these sonnets, if he reads or hears them at all.

All that said as a general caveat, Sonnet 36 breaks fascinating new ground. It states quite categorically two 'facts', or at any rate perceived facts, that stand at odds with each other: one, we two are one; two, we two must be apart. Having just admonished the young man for having done wrong, it now speaks of the "blots that do with me remain," without expounding what these blots are, and so we do not know whether William Shakespeare is taking the notion of two lovers being one to its ultimate consequence by saying you have done me wrong by – as we saw in the previous sonnet – clearly committing some sexual misdeed and because we are one the stain that this causes on your reputation is now also on me, and so therefore to protect you I shall bear this blot without you by myself so that your standing in society is not further threatened, or is William Shakespeare taking what has just happened as his opportunity to load blame and contrition upon himself for what he has done himself with and in relation to other people, such as, perhaps the person whom the young man seems to have 'stolen' from him. Either are possible, as is a combination of the two.

Sonnet 36 gives no answers to this question: all it says, with a great deal of conviction, is that this shame or dishonour that is now upon me is something I shall have to bear by myself, I will protect you as best I can from being dragged down with me, and, significantly, this calamity does not stem from anything you or I have done in relation to each other, because "our undivided loves are one." This thing that we are talking about is caused by a "separable spite" in our lives, in other words: an external factor that is not purely coincidental but that appears to have some malign intent against us.

Sonnets 40, 41, and then particularly 42 will give us a great deal more insight into what is likely to have been the cause for the crisis that triggered the previous three sonnets, and it is entirely possible, though not certain, that this Sonnet 36 also attempts to deal with the same situation.

And here is where, exceptionally, we may do well to avail ourselves of one of the rare external sources to lend a bit of tantalising context. Again, it behoves me to urge caution and to emphasise that we cannot know whether this reference here applies or not, all we can say is that it exists, and that it could well match up. And the best reason we have for even introducing it here is simply that the sonnet on its own poses such an odd proposition that in itself seems to beg for a bit of context.

In September 1594, a writer named Henry Willobie published in pamphlet format a narrative poem entitled Willobie His Avisa. It would go way too far to enter in on any detail about this piece which was not then and is not now held in high literary regard. But this did not stop it from being exceptionally popular, allowing it to go into several reprints, even though – or quite possibly because – it was also censored and banned for a while, five years after its initial publication.

The piece is interesting because it talks of a W. S. and his close or, as its author puts it, 'familiar' friend H. W. who share "the curtesy" of a "like passion" for a lady, resulting in a "like infection." The initials H. W. of course are compatible with Henry Willobie, but although a Henry Willobie existed, some people doubt that he actually wrote this. H. W. certainly though are also the initials of Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, and while nobody seriously believes he wrote the pamphlet, he is one of the strongest candidates for the Fair Youth and thus the person whom all of these sonnets so far are addressed to or about, as we discussed a little while ago and will examine in a great deal more detail in episodes to come.

Without wishing to read too much into any of this, and whether any of it is based in actual fact, in mere gossip, or some person's fertile imagination, this much we can say: in September 1594, at a time when the relationship between William Shakespeare and the young man may well be established enough for it to entail all the components we have come across thus far, and when Shakespeare would have had reason and opportunity to leave London because of the plague and also return to be reunited with his lover; at a time when he would now have turned thirty and the most likely candidate for his young lover within this time frame would be approaching 20, somebody publishes a piece of print that is so full of coded references, allusions, and nudging innuendo that the general public lap it up even though it isn't very good, the authorities ban it until after the death of Queen Elizabeth I, and one of the central constellations in it appears to mirror to some extent the events in the sonnets that could absolutely have been written around that time. That is all we know.

We don't know whether the person who wrote Willobie His Avisa was deliberately referencing the Queen herself or her court or people around her court when he made the maid protagonist of his poem, Avisa, sign her letters with the words "always the same," which just happens to be a direct English translation of the Queen's motto semper eadem, We don't know whether he meant to implicate William Shakespeare with his W. S. character, let alone Henry Wriothesley with his young but familiar friend H. W., and we don't know exactly what the implication is of the claim contained in the publication that “there is some thing under these false names and showes that hath been done truly.”

What we do know is that if such a pamphlet was published at a time when our Will and his young man were undergoing a relationship crisis caused by the young man 'stealing' or 'robbing' – as Sonnet 35 strongly suggests – a person whom William Shakespeare considered to be his, then this would, in London at the time, be widely known and talked about, and if it involved, as it may well have done and as so far we have been led to believe, a notable, extremely well-connected young nobleman, this would heighten the stakes considerably. If the two people thus satirised are indeed William Shakespeare and Henry Wriothesley, who, after all was brought up as the ward of Lord Burleigh, chief advisor to the Queen, then the situation could potentially be explosive. And so this "separable spite" that has burrowed itself into the union between these two men may suddenly be exceptionally real. The young man getting off with someone is one thing. The young man getting off with my own lover, affair, bit on the side, mistress, is quite another. Any of this being made public, or as near as public as anyone would dare, even though it be in coded language: that is a scandal in the most applicable sense. The town would be talking about this, the young man's reputation would be severely threatened, the Queen herself may be incensed. And that is not a fire you want to play with...

We have swerved and departed unusually far from the words themselves. The words of this Sonnet 36 make no mention of Willobie, of Avisa, of the Queen. They don't directly refer to the young man's transgression and they certainly don't give us a date to plot on the timeline. What they do give us is an indication that if I am William Shakespeare and you are a young English nobleman of some considerable note, then no matter how much we two love each other, there is a world out there, and this world is not all accepting, embracing, and benign. There are adverse factors out there, and some of these factors may well be just people who, for whatever reason – be it envy, be it disapproval, be it arrogance or ignorance – and given the chance, would come between us.

Sonnet 36 seems to stand on its own in this acute awareness of what other people think or say about us. And for quite a while it does. This tone, and this conscious reflection on the outside world does not reappear for another thirty-odd sonnets. Before then though, we will get many twists and turns and many profound reflections from Shakespeare on life, and time, and death, and beauty, and love.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!