Sonnet 23: As an Unperfect Actor on the Stage

|

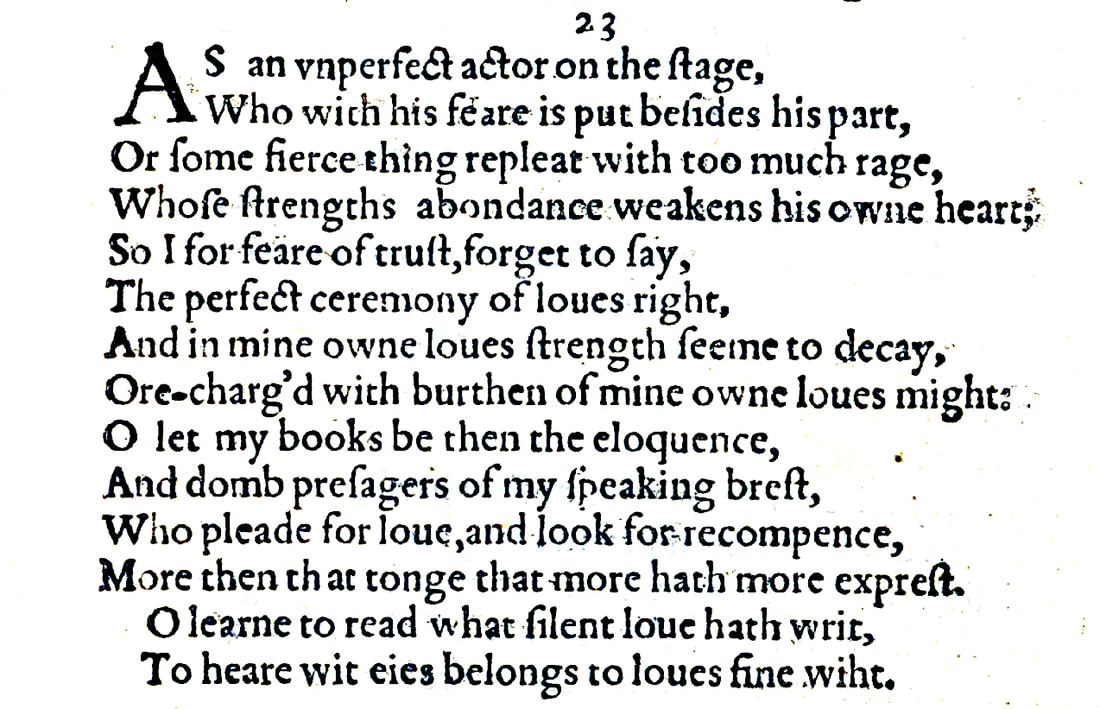

As an unperfect actor on the stage,

Who with his fear is put besides his part, Or some fierce thing replete with too much rage Whose strength's abundance weakens his own heart, So I, for fear of trust, forget to say The perfect ceremony of love's rite, And in mine own love's strength seem to decay, Orecharged with burden of mine own love's might. O let my books be then the eloquence And dumb presagers of my speaking breast, Who plead for love and look for recompense More than that tongue that more hath more expressed. O learn to read what silent love hath writ: To hear with eyes belongs to love's fine wit. |

|

As an unperfect actor on the stage,

Who with his fear is put beside his part, |

Like an actor onstage who doesn't know his lines properly – who is not word perfect, and therefore un-perfect – and who is beside himself with his stage fright and thus also put "beside his part," meaning unable to act it well...

|

|

Or some fierce thing replete with too much rage

Whose strength's abundance weakens his own heart, |

...or some fierce creature that is full of rage – "thing" here most likely refers to an unspecified animal, though it could also of course be a person who is overcome with anger – the strength of which – the anger's or the rage's abundance – paralyses him...

|

|

So I, for fear of trust, forget to say

The perfect ceremony of love's rite, |

...so I, unable to trust myself because I lack confidence, forget to say the perfect words that are expected of me as part of the normal rituals of love...

There is debate among some editors as to how to interpret "for fear of trust," and some argue it should be read as meaning: 'out of fear of the trust that you have put in me', but this sounds like a far less common and therefore less likely occurrence than someone simply lacking confidence in themselves and so not finding the right words to say. |

|

And in mine own love's strength seem to decay

Orecharged with burden of mine love's might. |

...and so the strength of my love seems to be waning or declining, when in fact I am just overcharged or overawed with the burden of the strength of my love for you.

Most editors render the Quarto Edition's ore-charg'd' as o'ercharged. |

|

O let my books be then the eloquence

|

Because of this, let my writings – 'books' here can be understood quite generally as the pieces I have written, most specifically by implication of course this poetry – be 'eloquent'...

|

|

And dumb presagers of my speaking breast,

|

...and thus the silent or mute messengers who speak on behalf of my heart which, though it may be 'speaking', cannot actually express how I feel and is therefore really more mute than these silent messengers.

'Presage' is an unusual word here to be employed in this context, because it really means 'predict' in Shakespeare's day, or, as today 'portend', but much as a 'herald' can be someone who announces something in advance, but can also be understood as the person or entity who relates some news, here Shakespeare may well be using 'presage' – which would normally suggest a foretelling – when what he really means is mostly 'communicate'. |

|

Who plead for love and look for recompense

|

They, my books – the presagers or messengers of my heart – plead for your love and look for a recompense, most likely to be understood in kind: they seek to be answered or returned with similar expressions of love...

A 'recompense' is of course also a payment or reward, and an allusion to the dynamic that exists between a poet and his patron may also be intended. The use of 'who', meanwhile, where we would say 'which' is very common in Shakespeare. |

|

More than that tongue that more hath more expressed.

|

...and they do so better and more sincerely than the tongue of that person who has seemingly expressed more by saying a lot more of apparently perfect words more often.

The repetition of 'more' is obviously there for rhythmic reasons, and it also most likely is intended to give us the idea that that kind of person here thought of – whether this is an actual individual or more generally a type – is effectively being tediously and unreliably verbose rather than eloquent with their words. |

|

O learn to read what silent love hath writ:

|

Learn to read what has been written by someone who loves you silently...

Silence is proverbially golden and although the phrase is not recorded in English until much later – it is attributed to Thomas Carlyle in the early 1830s as an import from the German 'reden ist Silber, schweigen ist Gold', the 'silent love' here is sure to be meant as of a higher quality than any loud love, inferred just above. |

|

To hear with eyes belongs to love's fine wit.

|

...being able to 'hear with eyes', in other words to read and, most importantly, to understand what has been written, is part of a refined, more sophisticated, knowledge and skill in love.

'Wit' here has this wider meaning, rather than our more specific application to a sharp, possibly humorous, mental capacity. |

The simultaneously self-conscious and also cautiously confident Sonnet 23 counsels the young man in the art of love, and in doing so it becomes the first one in the series to signal an uncertainty on William Shakespeare's part about the level to which the young man's love for him matches his own love for the young man, in both degree and sophistication. And it is also the first sonnet to tell us that while Shakespeare still fully believes in the power of his written words, he has a tendency to become tongue-tied when in the presence of his young lover.

With its mixture of doubt and certainty, plea and gentle admonishment, Sonnet 23 marks a noteworthy departure in tone from everything that has gone before, and it gives us a first hint of a glance at the young man's attitude or personality in relation to the poet. Because if I, William Shakespeare, find myself moved to tell the young man that I, "for fear of trust forget to say" the things that are apparently expected of me, then this yields up two insights straight away:

Firstly, there clearly are or have been occasions when I am in the presence of my young lover, which means we do have the kind of relationship that brings us face to face.

This has so far been assumed, of course, but only in fact sporadically expressed: in Sonnet 10 we hear Shakespeare say to the young man "be as thy presence is, gracious and kind," which is the first time we get a reasonably clear indication that Shakespeare actually has experienced the presence of the young man. In Sonnet 14, Shakespeare says that "from thine eyes my knowledge I derive," which – always assuming, for want of any good reason not to, that we can read these specific lines fairly literally – suggests that I, the poet, have actually looked into your, the young man's, eyes. Sonnet 15 with "sets you most rich in youth before my sight" may or may not reference an actual encounter, and from then on, right through to Sonnet 22, these poems, for all their awe and wonder, their cheekiness and innuendo, actually do not give any further indication as to whether we find ourselves mostly in Shakespeare's imagination or equally in the physical world.

Here now, though, we are left in little doubt, because in an age before telephony or radio communication, let alone the internet or mobiles, the only way anyone could be expected to hear anything of what anyone else was saying to or about them would be in their actual presence. We can reasonably infer from the existence of this sonnet then that William Shakespeare and the young man are 'seeing each other', at least in as much as there has been at the very least one further occasion on which they have met in person. In the broader context of these sonnets, we can of course almost as reasonably assume that they are 'seeing each other' by now on an at least plausibly regular basis and that – as we saw with Sonnet 21 – William Shakespeare has received the impression, or at the very least believes to have received the impression, that the young man has given him his heart quite as much as he, Shakespeare, clearly gave his to him.

Secondly, I, the poet, William Shakespeare, get tongue-tied. I, the podcaster, and also writer, Sebastian Michael, can readily relate to this. I cannot think on my feet. I can express myself reasonably well I believe in writing, when I have time to collect my thoughts and go over them and adjust them and phrase them and arrange them and edit them and revise them. Put on the spot, I effectively go blank. I forget best friends' names and what I had for lunch the same day when I'm under pressure. I am useless at networking and I absolutely go speechless when confronted with somebody I am in awe of, be this reasonably so or no. So hearing that William Shakespeare is unable to keep up with some of the witty, charming, maybe flirtatious conversation a young nobleman might expect of him comes as zero surprise to me. Nor that he should refer the man he is in love with to his writings. I have communicated some of the most important things I've had to say to people closest to me, not in person, not on the phone, not on Zoom – which didn't exist then, even though we're talking about thirty years ago, rather than four hundred – but in writing. Because that's how I knew how to say them.

The advice then, that the young man receives from his somewhat older lover is, as far as I can tell, entirely sound:

O learn to read what silent love hath writ

To hear with eyes belongs to love's fine wit.

And there is a third, maybe more indirect, insight that Sonnet 23 opens up for us: a disturbance has made itself felt. We still don't know, of course, anything about how the young man responds to these sonnets, if at all, or even whether he gets to read them, though the assumption certainly has been, and quite reasonably, that he does. But in order for William Shakespeare to explain his inability to say the right thing when required to do so and to then subtly but very clearly advise his young lover to acquire the skill of reading and appreciating the poetry that is being composed for him, he, the young man must have done or said something that prompts this response: it does not make sense for a sonneteer in the flush of fresh love to go on the defensive in this way for no reason.

Whether the young man has actually said something directly, or whether he has let some displeasure be known or shown through the absence of a reaction, or whatever else exactly may have happened we do not know and may never know. But this fact alone, that everything is not perfect in the dynamic between Shakespeare and the young man is supremely interesting. Because this is the first glimpse we get of this kind at the inner workings of that dynamic. All we had received so far was the increasingly abundant adoration on Shakespeare's part of the young man and a gradual evolution of the relationship from fairly generic and distanced to quite intimate, albeit thus far – as we saw in Sonnet 20 – explicitly non-sexual.

Here now, this changes. Not dramatically, in fact quite subtly, but perceptibly and significantly. With Sonnet 23, the relationship – or, to be more precise, our understanding of the relationship – becomes more nuanced, more complex, more human: this is the first sonnet to reflect just a hint of the actual interplay between Shakespeare and the young man, and we must assume from the words in this sonnet that the young man has not been all sweetness and wonder and exclusively complimentary to our poet. What the words of this sonnet strongly suggest, even if they don't spell this out, is that the young man either told Shakespeare directly that he, Shakespeare, doesn't seem to love him all that much if he can't even say so, or has let him know indirectly that he expects more, either by comparing what Shakespeare has said to him to what somebody else has said to him, or by referring possibly to what other poets and/or lovers generally are known or believed to say to the people they purport to love.

What this gives us then, and also for the first time, is a more multi-dimensional characterisation of the young man. For Shakespeare to conclude his sonnet with the advice that it contains and to refer to "love's fine wit" suggests that the young man needs this advice, that his love, such as it is, does not demonstrate much finesse or cultivation. And indeed, the tonality of the sonnet here does not lead us to believe that these words are addressed to a young man who is merely naive and innocent. The way they are formulated and structured much more suggests someone who is what today we might call rather entitled: someone who makes certain demands and fully expects those to be met in a fairly blunt, so as not to say blatant, way.

Sonnet 23 thus moves us onto a new plateau again. One on which the relationship between William Shakespeare and his young lover becomes more plastic – in a sculptural sense, not in a cheapened sense – more intricate, more layered. As ever, we want to be careful about any pronouncements we make and about how much we 'interpret', but this is the impression we are certainly getting and it is one that is just about to be corroborated with the marvellously complex Sonnet 24, before, with the oft rendered Sonnet 25 and the much less famous but no less impactful Sonnet 26, things take a couple of whole new turns again.

There were no roller coasters in Shakespeare's day, but had there been, he would soon find himself reminded of one just from what he's about to go through with his love for this young man...

With its mixture of doubt and certainty, plea and gentle admonishment, Sonnet 23 marks a noteworthy departure in tone from everything that has gone before, and it gives us a first hint of a glance at the young man's attitude or personality in relation to the poet. Because if I, William Shakespeare, find myself moved to tell the young man that I, "for fear of trust forget to say" the things that are apparently expected of me, then this yields up two insights straight away:

Firstly, there clearly are or have been occasions when I am in the presence of my young lover, which means we do have the kind of relationship that brings us face to face.

This has so far been assumed, of course, but only in fact sporadically expressed: in Sonnet 10 we hear Shakespeare say to the young man "be as thy presence is, gracious and kind," which is the first time we get a reasonably clear indication that Shakespeare actually has experienced the presence of the young man. In Sonnet 14, Shakespeare says that "from thine eyes my knowledge I derive," which – always assuming, for want of any good reason not to, that we can read these specific lines fairly literally – suggests that I, the poet, have actually looked into your, the young man's, eyes. Sonnet 15 with "sets you most rich in youth before my sight" may or may not reference an actual encounter, and from then on, right through to Sonnet 22, these poems, for all their awe and wonder, their cheekiness and innuendo, actually do not give any further indication as to whether we find ourselves mostly in Shakespeare's imagination or equally in the physical world.

Here now, though, we are left in little doubt, because in an age before telephony or radio communication, let alone the internet or mobiles, the only way anyone could be expected to hear anything of what anyone else was saying to or about them would be in their actual presence. We can reasonably infer from the existence of this sonnet then that William Shakespeare and the young man are 'seeing each other', at least in as much as there has been at the very least one further occasion on which they have met in person. In the broader context of these sonnets, we can of course almost as reasonably assume that they are 'seeing each other' by now on an at least plausibly regular basis and that – as we saw with Sonnet 21 – William Shakespeare has received the impression, or at the very least believes to have received the impression, that the young man has given him his heart quite as much as he, Shakespeare, clearly gave his to him.

Secondly, I, the poet, William Shakespeare, get tongue-tied. I, the podcaster, and also writer, Sebastian Michael, can readily relate to this. I cannot think on my feet. I can express myself reasonably well I believe in writing, when I have time to collect my thoughts and go over them and adjust them and phrase them and arrange them and edit them and revise them. Put on the spot, I effectively go blank. I forget best friends' names and what I had for lunch the same day when I'm under pressure. I am useless at networking and I absolutely go speechless when confronted with somebody I am in awe of, be this reasonably so or no. So hearing that William Shakespeare is unable to keep up with some of the witty, charming, maybe flirtatious conversation a young nobleman might expect of him comes as zero surprise to me. Nor that he should refer the man he is in love with to his writings. I have communicated some of the most important things I've had to say to people closest to me, not in person, not on the phone, not on Zoom – which didn't exist then, even though we're talking about thirty years ago, rather than four hundred – but in writing. Because that's how I knew how to say them.

The advice then, that the young man receives from his somewhat older lover is, as far as I can tell, entirely sound:

O learn to read what silent love hath writ

To hear with eyes belongs to love's fine wit.

And there is a third, maybe more indirect, insight that Sonnet 23 opens up for us: a disturbance has made itself felt. We still don't know, of course, anything about how the young man responds to these sonnets, if at all, or even whether he gets to read them, though the assumption certainly has been, and quite reasonably, that he does. But in order for William Shakespeare to explain his inability to say the right thing when required to do so and to then subtly but very clearly advise his young lover to acquire the skill of reading and appreciating the poetry that is being composed for him, he, the young man must have done or said something that prompts this response: it does not make sense for a sonneteer in the flush of fresh love to go on the defensive in this way for no reason.

Whether the young man has actually said something directly, or whether he has let some displeasure be known or shown through the absence of a reaction, or whatever else exactly may have happened we do not know and may never know. But this fact alone, that everything is not perfect in the dynamic between Shakespeare and the young man is supremely interesting. Because this is the first glimpse we get of this kind at the inner workings of that dynamic. All we had received so far was the increasingly abundant adoration on Shakespeare's part of the young man and a gradual evolution of the relationship from fairly generic and distanced to quite intimate, albeit thus far – as we saw in Sonnet 20 – explicitly non-sexual.

Here now, this changes. Not dramatically, in fact quite subtly, but perceptibly and significantly. With Sonnet 23, the relationship – or, to be more precise, our understanding of the relationship – becomes more nuanced, more complex, more human: this is the first sonnet to reflect just a hint of the actual interplay between Shakespeare and the young man, and we must assume from the words in this sonnet that the young man has not been all sweetness and wonder and exclusively complimentary to our poet. What the words of this sonnet strongly suggest, even if they don't spell this out, is that the young man either told Shakespeare directly that he, Shakespeare, doesn't seem to love him all that much if he can't even say so, or has let him know indirectly that he expects more, either by comparing what Shakespeare has said to him to what somebody else has said to him, or by referring possibly to what other poets and/or lovers generally are known or believed to say to the people they purport to love.

What this gives us then, and also for the first time, is a more multi-dimensional characterisation of the young man. For Shakespeare to conclude his sonnet with the advice that it contains and to refer to "love's fine wit" suggests that the young man needs this advice, that his love, such as it is, does not demonstrate much finesse or cultivation. And indeed, the tonality of the sonnet here does not lead us to believe that these words are addressed to a young man who is merely naive and innocent. The way they are formulated and structured much more suggests someone who is what today we might call rather entitled: someone who makes certain demands and fully expects those to be met in a fairly blunt, so as not to say blatant, way.

Sonnet 23 thus moves us onto a new plateau again. One on which the relationship between William Shakespeare and his young lover becomes more plastic – in a sculptural sense, not in a cheapened sense – more intricate, more layered. As ever, we want to be careful about any pronouncements we make and about how much we 'interpret', but this is the impression we are certainly getting and it is one that is just about to be corroborated with the marvellously complex Sonnet 24, before, with the oft rendered Sonnet 25 and the much less famous but no less impactful Sonnet 26, things take a couple of whole new turns again.

There were no roller coasters in Shakespeare's day, but had there been, he would soon find himself reminded of one just from what he's about to go through with his love for this young man...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!