Sonnet 84: Who Is it That Says Most, Which Can Say More

|

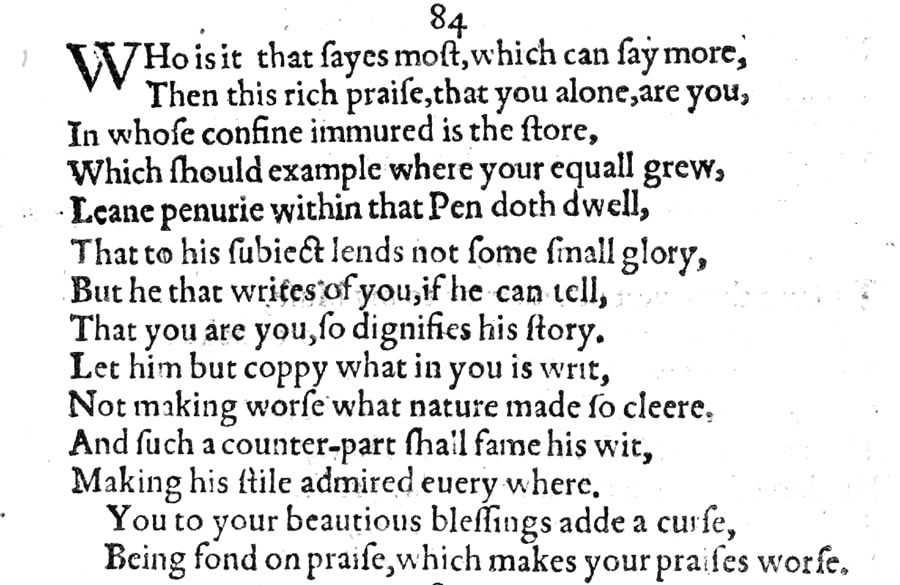

Who is it that says most, which can say more

Than this rich praise: that you alone are you, In whose confine immured is the store Which should example where your equal grew. Lean penury within that pen doth dwell That to his subject lends not some small glory, But he that writes of you, if he can tell That you are you, so dignifies his story. Let him but copy what in you is writ, Not making worse what nature made so clear, And such a counterpart shall fame his wit, Making his style admired everywhere. You to your beauteous blessings add a curse, Being fond on praise, which makes your praises worse. |

|

Who is it that says most, which can say more

Than this rich praise: that you alone are you, |

The poem further develops the argument from the two previous Sonnets, 82 and 83, and now, those having established that the young man does not need 'painting in words', meaning elaborate, flattering praise, drills down to the question of what constitutes 'good' or genuine praise:

Who – as in which poet, or even what kind of poet – is it that says most – as in most truthfully talks about you – and which poet or also which poetry can say more about you and can therefore present you better than a poet or poetry that offers you this rich – and also, as it happens, straightforward – praise: that you alone are you: you are unique and unequalled. As I am about to explain. |

|

In whose confine immured is the store

Which should example where your equal grew. |

You are uniquely you and within the boundary of your being is enclosed everything – all the qualities, all the characteristics, in a physical sense what we today would call the DNA – which should and therefore would serve as an example or as the prototype to the world for anyone who could conceivably be your equal. Or put differently: only someone who is entirely modelled on you could possibly come close to being as perfect as you are.

'Immured', here pronounced as three syllables, immured, on its own would – as several editors note – suggest a form of imprisonment, but with the verb 'grew' at the end of the quatrain, it more helpfully alludes to a walled garden, where this 'store' of qualities can be nurtured and cultivated. An interesting reference – possibly intended, possibly accidental – lies in the word 'store'. We have come across it several times before, first in the Procreation Sequence, where Shakespeare tells the young man in Sonnet 11: Let those whom nature hath not made for store, Harsh, featureless, and rude, barrenly perish, And then in Sonnet 14: But from thine eyes my knowledge I derive, And, constant stars, in them I read such art As truth and beauty shall together thrive If from thyself to store thou wouldst convert; In each of these cases, 'store' carries a meaning of the young man's qualities being deposited in, and thus passed on, in his offspring, almost literally as his DNA. In Sonnet 37, Shakespeare sees the young man's "beauty, birth, or wealth, or wit" as the 'store' to which he will make his love 'engrafted', and Sonnets 67 & 68 have nature itself treat the young man's beauty and qualities as the store for generations to come. It's a through line that further points towards a continuity in these poems and that seems to support our thesis that they are, indeed, all addressed to or about the same young man. |

|

Lean penury within that pen doth dwell

That to his subject lends not some small glory, |

It is a poor poet who does not lend his subject at least some sort of glory.

The 'lean penury' purposely contrasts the great abundance conjured by the 'store' above, and 'pen' here as elsewhere simply stands for the poet using that pen. In other words: if you are a poet writing about someone, then the very least that is expected of you is that you make this person sound and look moderately good. |

|

But he that writes of you, if he can tell

That you are you, so dignifies his story. |

But the poet who writes of you, if he can express you in his poetry as you are, if he can bring out your essence, your uniqueness that I mentioned earlier, then in doing so he adds dignity and credibility and substance to his writing.

'Story' here refers to the poet's output generally, it does not necessarily require a structured narrative, and as we noted on previous occasions, the fact that Shakespeare here is talking about a male poet is largely congruent with the culture of the day when the vast majority of published poets are men, and also of course he has one particular poet in mind: his rival, who is clearly a man. |

|

Let him but copy what in you is writ,

Not making worse what nature made so clear, |

Let this poet – any poet – who writes of you simply present you as you are: copy you word for word, so to speak, simply and plainly note what nature has bestowed on you and write this down as truthfully and faithfully as he can, and let him not through his inadequate writing make worse something that nature itself has set out and formulated so clearly in you.

This strongly echoes and enforces the claim of Sonnet 83: For I impair not beauty, being mute, When others would give life and bring a tomb. I do not make worse what nature herself made so clear in you, because I do not attempt to improve on this perfection of yours by splurging excessive verbiage on you. |

|

And such a counterpart shall fame his wit,

Making his style admired everywhere. |

And such a representation of you, a piece of writing that portrays you in this way as you are, no more and no less, will make this poet's wit, here meaning his skill, his adeptness in his art, famous and his writing style admired everywhere.

This turns out to be the case: while we don't know who this other poet is, we can say with absolute certainty that he is nowhere near as celebrated, as famous, as admired everywhere as Shakespeare who, by saying almost nothing descriptive about the young man, still manages to paint a fairly clear picture of him in our minds with these sonnets. |

|

You to your beauteous blessings add a curse,

Being fond on praise, which makes your praises worse. |

You add a curse to your beautiful blessings by being fond of praise which actually diminishes it.

The 'beauteous blessings' are of course the young man's beauty, but as we have seen on numerous occasions, these are meant to be accompanied by an internal beauty, and they are roundly augmented by the young man's birth, meaning his status in society, his wealth, and his wit, meaning his intelligence and education: the young man – of this we need have little doubt – pretty much has it all, but to these many and fulsome blessings of his he adds a curse by being so needy, so keen on and fond of praise. In other words, his vanity wrecks his character. The relative clause "which makes your praises worse" works on several levels and that – again as so very often – is surely entirely intentional. It can mean, most obviously: a) The fact in itself that you are so fond of praise makes any praise of you worse because it diminishes the sincerity and validity of any praise offered, since you so indiscriminately seek and accept it. b) You are fond of the kind of praise which diminishes itself in value because it is hyperbolic and insincere. But also, less immediately obvious: c) This fondness you have of praise makes any praise that you give – such as to your poet for their writing – worse, because you hand it out indiscriminately. Whereby it is worth noting that this latter meaning, which positions the young man as the giver of praise, may or may not be fully intended, since Sonnet 85 continues to use 'your praise' to mean strictly the praise others give to you, not the praise you offer in return. In fact, not since Sonnet 79 has Shakespeare concerned himself with what thanks or praise the young man may have for his poet, and there he discouraged him from even handing it out: Then thank him not for that which he doth say, Since what he owes thee, thou thyself dost pay. |

With Sonnet 84, William Shakespeare continues and underpins his defence of himself against the charge, referenced explicitly in Sonnet 83, that he has failed to present his young lover with sufficiently effusive praise and instead remained silent about his unparalleled qualities: not only is it the case – as he told the young man there – that you do not need 'painting' in elaborate words since these words, no matter how they try, can never actually do you justice, but in fact the greatest compliment anyone can pay you, this sonnet now postulates, is that you are exactly as you are: what a poet really needs to do is bring out the essence of you, and if he succeeds in this, then and only then can he truly lay a claim to fame as a writer, at any rate in relation to you.

And more true to his word than perhaps his argument sets out to be, Shakespeare closes this sonnet with his strongest rebuke of the young man since Sonnet 69, but unlike there, he doesn't follow this with a hasty absolution, but with one more poem to drive home his point.

As a writer, I have on occasion got into trouble over my use of punctation, or lack thereof. In my plays I have taken this to its most radical level by doing away with punctuation altogether and structuring the language instead in lines that allow the actor and reader make sense of what is being said. It works extremely well and most actors take to it, even perhaps after a while being to love that way of laying out a page, but takes a bit of getting used to. Even in prose though I would often use punctuation idiosyncratically, and I tend to very much agree with Gertrude Stein who holds that "the question mark is really part of the statement, not part of the question," (Lectures in America) and therefore dispenses it sparingly, if at all.

In this instance, Shakespeare, though he predates Stein by a good 300 years, also would appear to agree with her, as he doesn't put a question mark anywhere in the opening two lines of his sonnet. And while it is worth reemphasising that punctuation in Shakespeare's day generally and in this collection of sonnets specifically is haphazard to say the least and more often than not down to the typesetter's habits more than the author's in-depth consideration – the liberal dotting of this poem with commas being a case in point – it is obvious that our Will here is not asking a question. He is introducing a second rhetorical phase to an argument which doesn't have time or need for an upward inflexion and answers itself in the same breath. This in itself is a fascinating point of note, because editors with this sonnet agonise over where to place their question mark here, when it is clearly entirely unnecessary and not therefore present in the original.

If we have been observing that from the sestet of Sonnet 82 onwards and then throughout Sonnet 83, Shakespeare gains in confidence and momentum, then this here continues, culminating in a statement that is no less true than it is strong. From halfway through the second quatrain with "But he that writes of you" Shakespeare really talks about himself, because he certainly does feel that he can write of the young man as he truly is, he told him as much in Sonnet 82:

Thou, truly fair, wert truly sympathised

In true, plain words by thy true-telling friend

Me. We reminded ourselves of this also when discussing Sonnet 83. And so while it may sound like Shakespeare is talking about a hypothetical other poet, advising him to "copy what in you is writ" and not make "worse what nature made so clear" he is effectively explaining to the young man just what he himself has been doing and importantly means to continue to do.

And in this lies an amazing insight into our poet's heart and mind, and one I can oh so relate to: the William Shakespeare of Sonnet 84 will not compromise. He will not give in. He understands perfectly what the young man and the current vogue for words wants of him but he's saying: nope. I'm not going to do it. If you want me to write for you in the currently fashionable formula – in this case the rhapsodic idealisation of you – then that won't be forthcoming. Certainly not in my writing. I can write a gushing dedication to a patron, as I have done or am about to do in my long narrative poem The Rape of Lucrece – and we will look at this in context and detail when we discuss potential candidates for this young man, who may or may not be the dedicatee of that piece – but what I will not do is be told by you or anyone how to write my poetry.

That is a bold move. And to then tell the young man – who may or may not be his actual patron and to whom he may or may not be actually financially indebted, but who is more than likely to hold a powerful position in London society and therefore may make Shakespeare's life a whole lot easier or more difficult at a whim – to tell him that he is being vain, that he is being beyond his elevated status supercilious, is taking a big risk.

And it shows care. If Shakespeare didn't care about this young man other than what he can get out of him, he could easily say to himself, and to the young man: fine. I'll scribble some eulogies in the style you expect me to. Anything to keep you happy and content and onside. But that's not what you do with someone you care, even worry, about, someone you want to be the best version of themselves they can be. With the person you love, be they your partner or your good friend, or your child, or your parent, if they behave in a way that you know diminishes them, you tell them so. Even if it means that in that moment they hate you. Despise you. Disagree with you.

The young man of these sonnets – whoever he is, and we will come to this question, trust me – at times behaves like a petulant child. At times like a spoilt brat. At times like an arrogant prick. Then like the gorgeous, gentle, glorious treasure he is. And he is without a shadow of a doubt young not only in years but also at heart. You sometimes hear people say of someone that they are an old soul and if that is true of anyone it is true of Shakespeare who in his writing displays an encompassing wisdom and understanding of human nature that is difficult to reconcile with the notion of a singular lifetime. Of the young man, the exact opposite would appear to be true. The young man is the Bosie to Will's Oscar Wilde. He is the privileged, lovely, but in actual fact unworldly because inexperienced and therefore obsessively self-centred ego that yet wants to be formed. And most tellingly, Shakespeare cares enough about him to want to help him form himself:

You to your beauteous blessings add a curse,

Being fond on praise, which makes your praises worse.

That's sound advice from a good friend, a good parent, or a good person who loves you. And it's a firm stance and clear boundary of someone who will not lower himself to just fawn on you. Others can do so, not I.

And if you think that's all reading a bit much into a not especially spectacular poem, then stay with me, because – as I mentioned in the last episode on Sonnet 83 – Shakespeare has more yet to say on this: he continues this argumentation, this defence of his approach for one more poem, Sonnet 85. where he then concludes by saying to the young man what he told us about him in Sonnet 21, what he told him directly in Sonnet 32, and what has been clear throughout this collection: other poets may compare you to the sun and the moon and the stars in the sky, other poets may come and go with their exceedingly good fakes, but I am constant and I am true and I may not say much, but I hold you in my thoughts and in my heart, and that must surely count for more than all the words in the world.

And more true to his word than perhaps his argument sets out to be, Shakespeare closes this sonnet with his strongest rebuke of the young man since Sonnet 69, but unlike there, he doesn't follow this with a hasty absolution, but with one more poem to drive home his point.

As a writer, I have on occasion got into trouble over my use of punctation, or lack thereof. In my plays I have taken this to its most radical level by doing away with punctuation altogether and structuring the language instead in lines that allow the actor and reader make sense of what is being said. It works extremely well and most actors take to it, even perhaps after a while being to love that way of laying out a page, but takes a bit of getting used to. Even in prose though I would often use punctuation idiosyncratically, and I tend to very much agree with Gertrude Stein who holds that "the question mark is really part of the statement, not part of the question," (Lectures in America) and therefore dispenses it sparingly, if at all.

In this instance, Shakespeare, though he predates Stein by a good 300 years, also would appear to agree with her, as he doesn't put a question mark anywhere in the opening two lines of his sonnet. And while it is worth reemphasising that punctuation in Shakespeare's day generally and in this collection of sonnets specifically is haphazard to say the least and more often than not down to the typesetter's habits more than the author's in-depth consideration – the liberal dotting of this poem with commas being a case in point – it is obvious that our Will here is not asking a question. He is introducing a second rhetorical phase to an argument which doesn't have time or need for an upward inflexion and answers itself in the same breath. This in itself is a fascinating point of note, because editors with this sonnet agonise over where to place their question mark here, when it is clearly entirely unnecessary and not therefore present in the original.

If we have been observing that from the sestet of Sonnet 82 onwards and then throughout Sonnet 83, Shakespeare gains in confidence and momentum, then this here continues, culminating in a statement that is no less true than it is strong. From halfway through the second quatrain with "But he that writes of you" Shakespeare really talks about himself, because he certainly does feel that he can write of the young man as he truly is, he told him as much in Sonnet 82:

Thou, truly fair, wert truly sympathised

In true, plain words by thy true-telling friend

Me. We reminded ourselves of this also when discussing Sonnet 83. And so while it may sound like Shakespeare is talking about a hypothetical other poet, advising him to "copy what in you is writ" and not make "worse what nature made so clear" he is effectively explaining to the young man just what he himself has been doing and importantly means to continue to do.

And in this lies an amazing insight into our poet's heart and mind, and one I can oh so relate to: the William Shakespeare of Sonnet 84 will not compromise. He will not give in. He understands perfectly what the young man and the current vogue for words wants of him but he's saying: nope. I'm not going to do it. If you want me to write for you in the currently fashionable formula – in this case the rhapsodic idealisation of you – then that won't be forthcoming. Certainly not in my writing. I can write a gushing dedication to a patron, as I have done or am about to do in my long narrative poem The Rape of Lucrece – and we will look at this in context and detail when we discuss potential candidates for this young man, who may or may not be the dedicatee of that piece – but what I will not do is be told by you or anyone how to write my poetry.

That is a bold move. And to then tell the young man – who may or may not be his actual patron and to whom he may or may not be actually financially indebted, but who is more than likely to hold a powerful position in London society and therefore may make Shakespeare's life a whole lot easier or more difficult at a whim – to tell him that he is being vain, that he is being beyond his elevated status supercilious, is taking a big risk.

And it shows care. If Shakespeare didn't care about this young man other than what he can get out of him, he could easily say to himself, and to the young man: fine. I'll scribble some eulogies in the style you expect me to. Anything to keep you happy and content and onside. But that's not what you do with someone you care, even worry, about, someone you want to be the best version of themselves they can be. With the person you love, be they your partner or your good friend, or your child, or your parent, if they behave in a way that you know diminishes them, you tell them so. Even if it means that in that moment they hate you. Despise you. Disagree with you.

The young man of these sonnets – whoever he is, and we will come to this question, trust me – at times behaves like a petulant child. At times like a spoilt brat. At times like an arrogant prick. Then like the gorgeous, gentle, glorious treasure he is. And he is without a shadow of a doubt young not only in years but also at heart. You sometimes hear people say of someone that they are an old soul and if that is true of anyone it is true of Shakespeare who in his writing displays an encompassing wisdom and understanding of human nature that is difficult to reconcile with the notion of a singular lifetime. Of the young man, the exact opposite would appear to be true. The young man is the Bosie to Will's Oscar Wilde. He is the privileged, lovely, but in actual fact unworldly because inexperienced and therefore obsessively self-centred ego that yet wants to be formed. And most tellingly, Shakespeare cares enough about him to want to help him form himself:

You to your beauteous blessings add a curse,

Being fond on praise, which makes your praises worse.

That's sound advice from a good friend, a good parent, or a good person who loves you. And it's a firm stance and clear boundary of someone who will not lower himself to just fawn on you. Others can do so, not I.

And if you think that's all reading a bit much into a not especially spectacular poem, then stay with me, because – as I mentioned in the last episode on Sonnet 83 – Shakespeare has more yet to say on this: he continues this argumentation, this defence of his approach for one more poem, Sonnet 85. where he then concludes by saying to the young man what he told us about him in Sonnet 21, what he told him directly in Sonnet 32, and what has been clear throughout this collection: other poets may compare you to the sun and the moon and the stars in the sky, other poets may come and go with their exceedingly good fakes, but I am constant and I am true and I may not say much, but I hold you in my thoughts and in my heart, and that must surely count for more than all the words in the world.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!