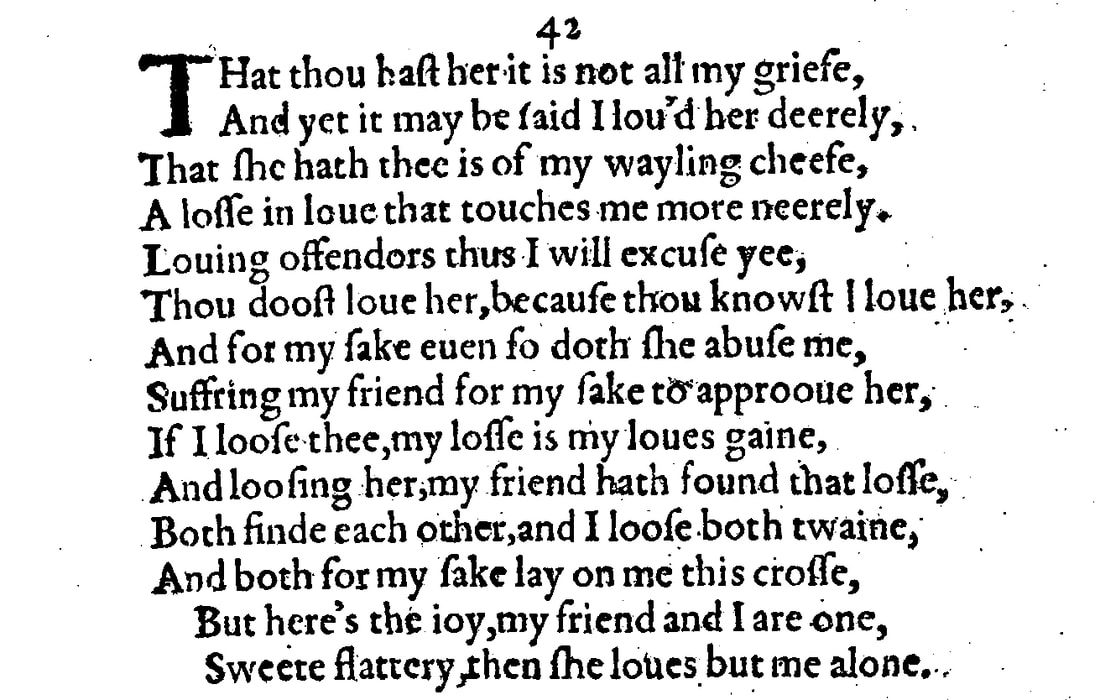

Sonnet 42: That Thou Hast Her, it Is Not All My Grief

|

That thou hast her, it is not all my grief,

And yet, it may be said I loved her dearly; That she hath thee is of my wailing chief: A loss in love that touches me more nearly. Loving offenders, thus I will excuse ye: Thou dost love her, because thou knowst I love her, And for my sake, even so, doth she abuse me, Suffering my friend for my sake to approve her. If I lose thee, my loss is my love's gain, And losing her, my friend hath found that loss; Both find each other, and I lose both twain, And both for my sake lay on me this cross. But here's the joy: my friend and I are one. Sweet flattery, then she loves but me alone. |

|

That thou hast her, it is not all my grief,

And yet it may be said I loved her dearly; |

The fact that you have had her is not all that grieves or saddens me, although it may be said that I loved her dearly...

The meaning of 'that thou hast her' is very obviously sexual, and this is significant not only in relation to this sonnet where it can't be doubted, but therefore also for other sonnets which are yet to come where the same way of expressing a sexual relation is often, and thus unnecessarily, considered to be ambiguous. How much we should read into the past tense in 'I loved her dearly', is, by contrast, not entirely certain. It implies, of course, that the love I bore her is now a thing of the past, but these are volatile emotional times and settings, and so we can't conclude from this that the relationship between Shakespeare and his mistress is therefore now by necessity over. |

|

That she hath thee is of my wailing chief,

A loss in love that touches me more nearly. |

The fact that she had you is what causes me most sorrow, because it is a loss in love that touches and therefore hurts me more directly.

In Sonnet 40 we noted an apparent equivalence between this other love and the young man, and we also flagged up there that this would soon be relativised. Here, indeed, Shakespeare draws a first clear distinction between these two loves of his, and quite a bit later in the series he will do so again, in even more unequivocal terms. |

|

Loving offenders, thus I will excuse ye:

|

You two, who you are both lovers and also both offenders and, clearly, offenders in matters of love, this is how I will excuse your wrongdoing:

|

|

Thou dost love her because thou knowst I love her

|

You love her, because you know that I love her...

|

|

And for my sake, even so, doth she abuse me,

Suffering my friend for my sake to approve her. |

...and in just the same way it is for my sake that she abuses me by allowing my friend – you, the young man – to give her a try.

'Approve' of course means to agree that something or someone is 'good' or 'good enough' or 'acceptable', but in Elizabethan English it also means 'to prove' or 'to show', and this sense of 'proving' – as in testing, or 'proofing' – is here clearly intended and partly serves to reinforce the notion put forward in Sonnet 40 that the young man with this woman has had a "wilful taste" of what he normally refuses, and that this 'love' that he has thus received is not a true love, but at best a wanton, even experimental one. The very transactional, even somewhat crude, note, then, is clearly deliberate. |

|

If I lose thee, my loss is my love's gain,

And losing her, my friend hath found that loss: |

If I lose you – to her, as we know – then the loss that I suffer through this, namely you, is her, my other love's gain. And in losing her, you, my 'friend', have then found that loss, because I lose her to you.

Unsurprisingly in a constellation that has become as complex as this, the language to describe it is multi-layered and entwined, so as not to say convoluted, and once again we may assume that Shakespeare is fully aware of this and means this to be the case. Because these two lines can be further interpreted as: When I lose you, whom in this poem I interchangeably address in the second person and refer to in the third person, then this loss that I have is also your gain, who you are also my love, because through losing you to her you gain her, and she then by you having her becomes my loss which you, my friend, have found. |

|

Both find each other, and I lose both twain,

|

You both find each other and I, in the process, lose the two of you...

'Twain', which we have encountered before in Sonnet 36 and also recently in Sonnet 39, simply means 'two'. |

|

And both for my sake lay on me this cross.

|

...and both of you put this burden and pain on me for my own sake, because you both do this only because you both love me.

|

|

But here's the joy: my friend and I are one.

|

But here is the joy that lies in all this and that stands in complete contrast to the grief and the wailing caused by this cross that you put on me: my friend – you, the young man – and I are one.

This has been variously established before: my heart lives in yours, yours in mine, we two are one; and it was the absence in Sonnet 39 – which, ironically, appears to have precipitated this crisis – that taught me how to make this one that we are be two, by praising you who are not here with me now. |

|

Sweet flattery, then she loves but me alone.

|

What a lovely delusion: that means she loves just me alone.

The whole contorted argument that tries to absolve the young man, and the woman for that matter, from any wrongdoing because they only do it for my sake is of course – as I, the poet, full well know – a grand delusion with which I flatter myself. But it is my way of dealing with it. So there... |

In the second of two sonnets that try to deal with the fallout from the young man's infidelity, William Shakespeare contorts himself into an argument that, really, both his young lover and his mistress did what they did only for the love they both bear him. That this is something of a delusion is a conclusion he himself comes to as easily as we do. Sonnet 42 nevertheless yields a valuable new insight into the suddenly so complex situation by drawing a clear distinction between the levels of priority and the types of connection William Shakespeare feels he has with the other two protagonists of what, without his own intention let alone approval, has turned into a remarkably post-modern love triangle.

The from our perspective perhaps most interesting facet of Sonnet 42 is possibly twofold: first its continued unabashed frankness about the nature of the relationships involved: you, my friend and lover, have had it off with her, my mistress, and I somehow have to reconcile this with my feelings for you both. Like Sonnet 41, Sonnet 42 leaves no doubt in our minds that the relationship between the young man and the woman involved is a sexual one, and while it gives us no further direct indication as to whether or not the relationship between William Shakespeare and the young man is at this point also a sexual one, it certainly treats the respective offences these two have committed against Shakespeare as essentially on a par.

Not though the relationships themselves. This is the other, and in many respects also even more compelling insight that Sonnet 42 makes manifest: my loss of you to her is the one that touches me more nearly than my loss of her to you, even though I loved her dearly, and who knows may even be able to do so again. But you clearly and obviously matter more.

This, while it provides abundant clarity about how William Shakespeare positions himself in relation to these two, is not in itself altogether surprising. Even allowing for the possibility that not all these sonnets are in the right order and that some that may have been written may also have been lost, others may – as we have already seen – have slipped into the wrong place, and in fact a whole section referring to an unknown woman and also to 'two loves' later in the collection may in fact sequentially belong here, it is evident that I, the poet, William Shakespeare, have by this stage written dozens of sonnets to, for, and about you, the young man, and either none yet, or, if we were to assume that the Dark Lady of the later sonnets is in fact this mistress and that they actually slot in here in terms of the timeline, very few to, for, or about her.

If the mistress is somebody else entirely, then there are no known sonnets to, for, or about her.

If we further assume, as quite reasonably we have done throughout, that the writing of these sonnets is at least to some extent – quite likely to a very large extent – prompted by actual real life events and constellations in Shakespeare's existence, then we may also and as reasonably assume that the person who matters most and who agitates the poet most will be the subject, addressee, or motive for most of these sonnets. And so it is in fact hardly surprising to learn, as we do here, that the young man matters a great deal more to Shakespeare than his mistress.

I don't want to anticipate the Dark Lady Sonnets here, because they in themselves provide a whole new level of depth to probe, but to foreshadow just a bit: the tone of these sonnets will be a different one entirely to the way in which Shakespeare talks about his young man.

Also important is that Sonnet 42 appears to support a notion we received from Sonnet 40, and briefly highlighted above in the 'translation', that it may well be the case that the young man has, with his encounter with Shakespeare's mistress, 'tasted', 'tried', or 'tested' something he normally or hitherto has been known to eschew. Namely, a woman. This may or may not really be the case, but both these sonnets drop hints to that effect. And in a way it too would actually make sense. If the young man, of whom we know that he, as I have frequently now put it, is obstinate in his refusal to marry, is simply not that interested in women and actually has no real sexual experience with any of them, then his choice of Shakespeare's mistress to give it a try is suddenly no longer so outlandish.

Imagine you are a young man of some considerable social status, of whom the world, including everybody around you, right up to the Queen of the country who has near absolute power and to whom you, like every other subject, are beholden, expects to get married and produce an heir, because that is what you have to do and there is no alternative lifestyle path open to you, then there comes the point at which you have to face the music and find out what it's actually like to be with a woman. So rather than go to a sex worker, which carries its own manifold risks and potential awkwardnesses, or bed a prospective bride, which would immediately negate her as a potential bride because she would then no longer be a virgin, or she would have to become your wife straight away, which you really are not keen on, why not be friendly with the woman whom your friend and lover is friendly with and whom he trusts and who may have heard a lot about you and who is evidently free with her sexuality without that being a great big issue for her or for anyone else that we know of. Why not – in our language today, which is of course inadequate for the time – pop your cherry with someone who is already familiar and who may treat you more like a good friend than like a conquest.

In this light, what otherwise and at first glance may look like a callous act of wanton appropriation, of peeved jealousy, or of selfish, almost childish, I-want-what-you-have-ness, suddenly seems possibly quite sensible, even almost endearingly coy behaviour. This young man is, after all, very young. He would be just about twenty now, and if it is who we have been given more and more compelling reason to believe it might be, Henry Wriothesley, the Third Earl of Southampton, he has also had a quite precocious upbringing as a lone child in the household of a very powerful man who is not his father but who is the chief advisor to the Queen herself.

William Shakespeare does not give this angle any direct expression, but from this angle, his almost ridiculously self-delusional attempt at letting the young man off the hook also makes a degree of sense. And if Sonnet 34 is to be believed, and indeed Sonnet 35, then the young man has presented a considerable degree of contrition:

Ah, but those tears are pearl that thy love sheds

And they are rich, and ransom all ill deeds.

Followed immediately by:

No more be grieved at that which thou hast done...

You don't say or, for that matter, write this to someone who has not shown any signs of remorse over their wrongdoing.

We have on one or two occasions before observed that Shakespeare and his contemporaries lived fast and intensive lives. Not least because they had to. The dangers of being alive were numerous, and many made it no further than into their early adult years. A third or so of all children never got to see adult years. Shakespeare and his young man simply did not have the luxury of growing into their early to mid thirties before starting to make meaningful decisions about the trajectory of their lives. More often than not, the trajectory of your life was prescribed as a given and you were expected and forced to grow up and get on with living, because you had, if you were lucky, twenty or thirty years to do it in as an adult. And if here, during this phase of his life, the young man is doing some growing up, some intimately acquainting himself with what will at least for a while have to be part of his reality, then none of this is really that weird any more. And that Shakespeare struggles to deal with this in a constructive manner isn't either. He does so with a noteworthy degree of self-knowledge: "Sweet flattery, then she loves but me alone." He doesn't expect us, or the young man, or her, to believe this any more than he does, but it allows him, at least for the time-being, to draw a line under the matter and to move on for now.

What follows next is a new wave form with new ups and downs that happen on a new level, but before then, I am extraordinarily pleased to announce that the next episode will be a special edition with our first guest, Professor Stephen Regan, author of The Sonnet, who will be talking to us about the sonnet as a poetic form.

The from our perspective perhaps most interesting facet of Sonnet 42 is possibly twofold: first its continued unabashed frankness about the nature of the relationships involved: you, my friend and lover, have had it off with her, my mistress, and I somehow have to reconcile this with my feelings for you both. Like Sonnet 41, Sonnet 42 leaves no doubt in our minds that the relationship between the young man and the woman involved is a sexual one, and while it gives us no further direct indication as to whether or not the relationship between William Shakespeare and the young man is at this point also a sexual one, it certainly treats the respective offences these two have committed against Shakespeare as essentially on a par.

Not though the relationships themselves. This is the other, and in many respects also even more compelling insight that Sonnet 42 makes manifest: my loss of you to her is the one that touches me more nearly than my loss of her to you, even though I loved her dearly, and who knows may even be able to do so again. But you clearly and obviously matter more.

This, while it provides abundant clarity about how William Shakespeare positions himself in relation to these two, is not in itself altogether surprising. Even allowing for the possibility that not all these sonnets are in the right order and that some that may have been written may also have been lost, others may – as we have already seen – have slipped into the wrong place, and in fact a whole section referring to an unknown woman and also to 'two loves' later in the collection may in fact sequentially belong here, it is evident that I, the poet, William Shakespeare, have by this stage written dozens of sonnets to, for, and about you, the young man, and either none yet, or, if we were to assume that the Dark Lady of the later sonnets is in fact this mistress and that they actually slot in here in terms of the timeline, very few to, for, or about her.

If the mistress is somebody else entirely, then there are no known sonnets to, for, or about her.

If we further assume, as quite reasonably we have done throughout, that the writing of these sonnets is at least to some extent – quite likely to a very large extent – prompted by actual real life events and constellations in Shakespeare's existence, then we may also and as reasonably assume that the person who matters most and who agitates the poet most will be the subject, addressee, or motive for most of these sonnets. And so it is in fact hardly surprising to learn, as we do here, that the young man matters a great deal more to Shakespeare than his mistress.

I don't want to anticipate the Dark Lady Sonnets here, because they in themselves provide a whole new level of depth to probe, but to foreshadow just a bit: the tone of these sonnets will be a different one entirely to the way in which Shakespeare talks about his young man.

Also important is that Sonnet 42 appears to support a notion we received from Sonnet 40, and briefly highlighted above in the 'translation', that it may well be the case that the young man has, with his encounter with Shakespeare's mistress, 'tasted', 'tried', or 'tested' something he normally or hitherto has been known to eschew. Namely, a woman. This may or may not really be the case, but both these sonnets drop hints to that effect. And in a way it too would actually make sense. If the young man, of whom we know that he, as I have frequently now put it, is obstinate in his refusal to marry, is simply not that interested in women and actually has no real sexual experience with any of them, then his choice of Shakespeare's mistress to give it a try is suddenly no longer so outlandish.

Imagine you are a young man of some considerable social status, of whom the world, including everybody around you, right up to the Queen of the country who has near absolute power and to whom you, like every other subject, are beholden, expects to get married and produce an heir, because that is what you have to do and there is no alternative lifestyle path open to you, then there comes the point at which you have to face the music and find out what it's actually like to be with a woman. So rather than go to a sex worker, which carries its own manifold risks and potential awkwardnesses, or bed a prospective bride, which would immediately negate her as a potential bride because she would then no longer be a virgin, or she would have to become your wife straight away, which you really are not keen on, why not be friendly with the woman whom your friend and lover is friendly with and whom he trusts and who may have heard a lot about you and who is evidently free with her sexuality without that being a great big issue for her or for anyone else that we know of. Why not – in our language today, which is of course inadequate for the time – pop your cherry with someone who is already familiar and who may treat you more like a good friend than like a conquest.

In this light, what otherwise and at first glance may look like a callous act of wanton appropriation, of peeved jealousy, or of selfish, almost childish, I-want-what-you-have-ness, suddenly seems possibly quite sensible, even almost endearingly coy behaviour. This young man is, after all, very young. He would be just about twenty now, and if it is who we have been given more and more compelling reason to believe it might be, Henry Wriothesley, the Third Earl of Southampton, he has also had a quite precocious upbringing as a lone child in the household of a very powerful man who is not his father but who is the chief advisor to the Queen herself.

William Shakespeare does not give this angle any direct expression, but from this angle, his almost ridiculously self-delusional attempt at letting the young man off the hook also makes a degree of sense. And if Sonnet 34 is to be believed, and indeed Sonnet 35, then the young man has presented a considerable degree of contrition:

Ah, but those tears are pearl that thy love sheds

And they are rich, and ransom all ill deeds.

Followed immediately by:

No more be grieved at that which thou hast done...

You don't say or, for that matter, write this to someone who has not shown any signs of remorse over their wrongdoing.

We have on one or two occasions before observed that Shakespeare and his contemporaries lived fast and intensive lives. Not least because they had to. The dangers of being alive were numerous, and many made it no further than into their early adult years. A third or so of all children never got to see adult years. Shakespeare and his young man simply did not have the luxury of growing into their early to mid thirties before starting to make meaningful decisions about the trajectory of their lives. More often than not, the trajectory of your life was prescribed as a given and you were expected and forced to grow up and get on with living, because you had, if you were lucky, twenty or thirty years to do it in as an adult. And if here, during this phase of his life, the young man is doing some growing up, some intimately acquainting himself with what will at least for a while have to be part of his reality, then none of this is really that weird any more. And that Shakespeare struggles to deal with this in a constructive manner isn't either. He does so with a noteworthy degree of self-knowledge: "Sweet flattery, then she loves but me alone." He doesn't expect us, or the young man, or her, to believe this any more than he does, but it allows him, at least for the time-being, to draw a line under the matter and to move on for now.

What follows next is a new wave form with new ups and downs that happen on a new level, but before then, I am extraordinarily pleased to announce that the next episode will be a special edition with our first guest, Professor Stephen Regan, author of The Sonnet, who will be talking to us about the sonnet as a poetic form.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!