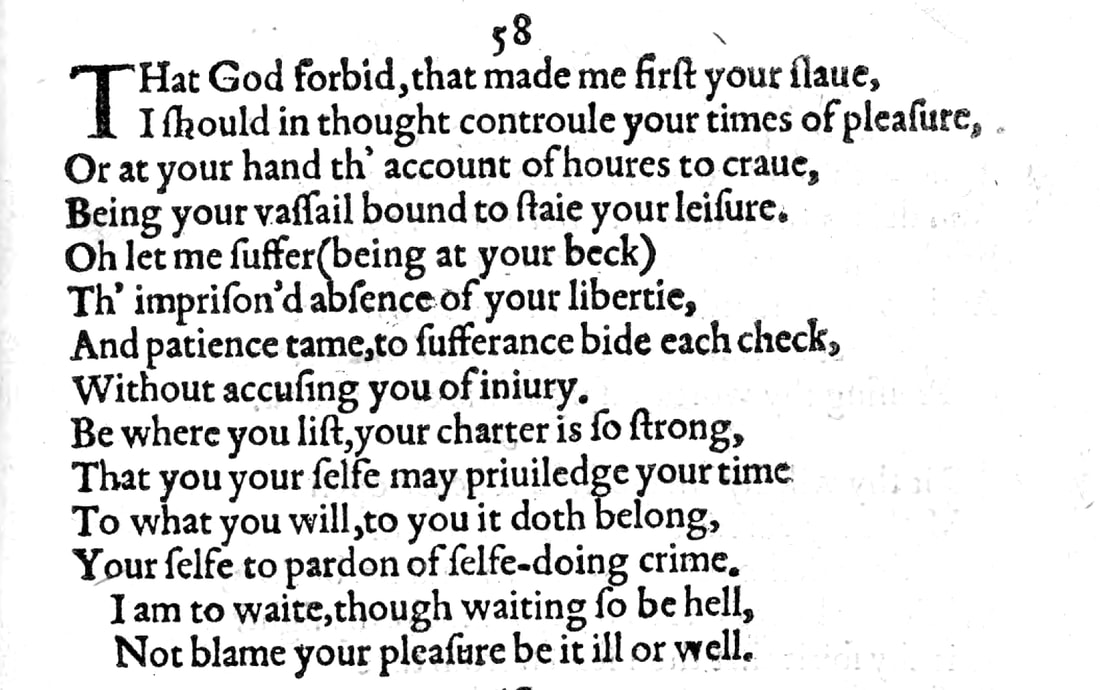

Sonnet 58: That God Forbid That Made Me First Your Slave

|

That God forbid that made me first your slave

I should in thought control your times of pleasure, Or at your hand th'account of hours to crave, Being your vassal, bound to stay your leisure. O let me suffer, being at your beck, Th'imprisoned absence of your liberty, And, patience-tame to sufferance, bide each check Without accusing you of injury. Be where you list, your charter is so strong That you yourself may privilege your time To what you will: to you it doth belong, Yourself to pardon of self-doing crime. I am to wait, though waiting so be hell, Not blame your pleasure, be it ill or well. |

|

That God forbid that made me first your slave

I should in thought control your times of pleasure |

God forbid – and that is the same God who made me your slave in the first place – that I should attempt to control your times of pleasure with or in my thoughts. Or put more simply: God forbid that I should try and work out what you get up to, since it is clearly none of my business...

Several editors suggest a reading of this first line as 'that particular god who first made me your slave', which would then imply Cupid or the god of love. But 'God' in the Quarto Edition is capitalised and the expression 'God forbid' features a further 21 times in Shakespeare's Complete Works, so reading this as an idiomatic expression makes much more sense to me. |

|

Or at your hand th'account of hours to crave,

Being your vassal, bound to stay your leisure. |

...or that I should want an account or breakdown of how you spend your time, being, as I am, your servant and therefore bound to await your orders or to remain quite literally 'in waiting' until you have use of me.

While the entire tone of Sonnets 57 & 58 in their subordination to the young lover is reminiscent of Sonnet 26, which starts with the lines Lord of my love to whom in vassalage Thy merit hath my duty strongly knit, this here is the clearest echo we get from it, with William Shakespeare once again invoking the notion of the feudal vassal, who is bound to a lord or king in allegiance but in return receives certain rights and privileges and also protection. |

|

O let me suffer, being at your beck,

Th'imprisoned absence of your liberty |

Being at your beck and call, let me suffer this feeling of a metaphorical imprisonment that I experience through your absence, which in turn is caused or licenced by your liberty...

A 'beck' is a nod or a wave that requests or demands someone's attention, as would be common of a lord or a lady, a king or a queen, to get their servant to do something. It stems from 'to beckon', which is to gesture or wave hither. A further dictionary definition (Oxford Dictionaries) renders it as "the slightest indication of will or command," which is of course exactly what such a gesture would suggest. While the 'absence' of the young man cannot, of course, itself be imprisoned, Shakespeare seems to be using the word here to mean 'imposed' or to cause a feeling of imprisonment, which stands in such stark contrast to the young man's freedom to do as he pleases at any given time. There is also an elegant double meaning in 'absence of your liberty': it on the one hand suggests your absence away from me, which, as just noted, is a consequence of your liberty or freedom; but on the other hand it also can be read as the absence in my life of your levels of liberty or freedom, in other words, the freedom that I lack. And 'liberty', beyond freedom, also references a libertine conduct, which once again would appear to suggest sexual wantonness. |

|

And, patience-tame to sufferance, bide each check

Without accusing you of injury. |

...and endure each restraint on my liberty, rebuff, or even rebuke patiently and without accusing you of doing anything wrong.

The string 'patience tame to sufferance', although it seems fairly clear what is meant by it, cannot be easily translated into contemporary prose, and the Quarto Edition's punctuation doesn't help. It goes: And patience tame, to sufferance bide each check, This yields several possible readings, none of which require a comma where it is, but all of which result in more or less the same effect. Several editors assume that the subject is still the poet who bides each check, which would make 'patience tame to sufferance' a descriptive clause, which is why you will often see it – as here – bracketed by commas and the expression 'patience-tame' hyphenated as an adjective. An equally valid reading comes about if we assume instead that the subject switches to patience, which would result in: And patience, tame to sufferance, bide each check whereby it is patience now that 'tame to sufferance' bides each check. Which still leaves the minor conundrum of what either 'patience-tame to sufferance' or 'tame to sufferance' exactly means: the implication is that either I, the poet, have been tamed to patiently endure the suffering that is imposed on me through your absence and your philandering, or that patience, which is in itself a virtue, is by nature tame and therefore able to endure suffering. But 'sufferance' also in itself means 'patient endurance' or 'long term suffering', so a strong sense is conveyed that William Shakespeare is used to the young man's whims and neglect. 'Bide' here simply means endure; and 'check', apart from the definitions already given, also invites a reading of 'stroke' or even setback: in Sonnet 15 we had When I perceive that men as plants increase, Cheered and checked even by the self-same sky where 'checked' meant 'to hinder, to obstruct, to hold back' or 'to reduce', possibly even, in our understanding today, 'to put in place'. |

|

Be where you list, your charter is so strong

That you yourself may privilege your time To what you will, to you it doth belong, |

Be wherever you want to be, your position in terms of your rights and entitlement is so strong that you yourself may decide how you use your time and may allocate it to whatever you choose, after all it belongs to you.

The verb 'to list' as well as the noun 'list' are archaic terms sadly no longer in use, to mean 'want' or 'like' for the verb and 'desire' or 'inclination' for the noun. |

|

Yourself to pardon of self-doing crime.

|

...and because it belongs to you, and your 'charter of rights or titles' is as strong as it is, you may pardon yourself of any crime that you yourself happen to commit.

In other words: your freedom and indeed privilege in the world is such that you may go whithersoever you wish and spend time in whatever manner with whomsoever you choose, and if from this any 'crime' or offence or transgression results, then you yourself are entirely within your rights to pardon yourself for them. The fact that 'crime' – which would suggest a rather strong offence or transgression – is even mentioned though suggests that Shakespeare clearly feels unease about the young man's conduct at his 'times of pleasure'... |

|

I am to wait, though waiting so be hell,

Not blame your pleasure, be it ill or well. |

I have to wait, although waiting in this way is hell for me, and I have no right to blame you for the pleasures you seek or pursue, be they now ill or well, meaning whether they are morally sound and permissible and in relation to me acceptable, or not.

|

Sonnet 58 continues from Sonnet 57 and elaborates on Shakespeare's startling sense of subservience to the young man. It simply picks up from the sentiment that "being your slave" I have to wait on and for you and affirms that in this lowly position I cannot presume to have any powers over your conduct or your whereabouts, and in fact I must not even attempt to gain any kind of control over this situation by thinking about what you are up to when you are away from me.

The two sonnets forming a pair with one coherent argument, here they are back to back, as they belong:

Being your slave, what should I do but tend

Upon the hours and times of your desire?

I have no precious time at all to spend,

Nor services to do, till you require.

Nor dare I chide the world-without-end hour

Whilst I, my sovereign, watch the clock for you,

Nor think the bitterness of absence sour

When you have bid your servant once adieu.

Nor dare I question with my jealous thought

Where you may be, or your affairs suppose,

But like a sad slave stay and think of nought,

Save where you are, how happy you make those.

So true a fool is love that in your will,

Though you do anything, he thinks no ill.

That God forbid that made me first your slave

I should in thought control your times of pleasure,

Or at your hand th'account of hours to crave,

Being your vassal, bound to stay your leisure.

O let me suffer, being at your beck,

Th'imprisoned absence of your liberty,

And, patience-tame to sufferance, bide each check

Without accusing you of injury.

Be where you list, your charter is so strong

That you yourself may privilege your time

To what you will: to you it doth belong,

Yourself to pardon of self-doing crime.

I am to wait, though waiting so be hell,

Not blame your pleasure, be it ill or well.

If Sonnet 57 managed to end on a perhaps resigned but still conciliatory note that acknowledged how great a fool a love such as the one experienced by our poet can make of us, Sonnet 58 deepens the sense of servitude conveyed by Sonnet 57 and at the same time heightens the level of sarcasm we can hear.

As in Sonnet 57, we may need to be somewhat careful in just how much of such self-conscious self-awareness we read into these two sonnets, but while in Sonnet 57 we still felt we had at least a good enough reason to accept the distinct possibility that Shakespeare is in fact being entirely sincere, with Sonnet 58 this becomes increasingly difficult.

The opening salvo itself to us sounds somewhat over the top: “That God forbid!” We still use the expression, but rarely nowadays with innocent sincerity. This is not strictly the case in Shakespeare: as previously observed, he uses the phrase often in his plays and certainly not always – in fact not even predominantly – with irony or let alone sarcasm.

And so it is possible that the first quatrain of Sonnet 58 may well be taken at face value. We have speculated quite extensively by now about the type of person – and sporadically early on also about the identity of the person – these sonnets are addressed to or about and although to us today the notion – outside perhaps some fetish context – that someone would describe themselves as someone else’s ‘vassal’ is somewhat strange at best and absurd at worst, it is entirely possible that Shakespeare genuinely sees himself in relation to the young man as economically dependent, socially inferior, and therefore morally obliged to him.

During the second quatrain, our whispering doubts gain in volume. There is a difference between being someone’s liegeman or vassal who, after all, possesses a certain level of agency and autonomy, and being at someone’s beck, which implies much more the status of a servant or a footman. And then positioning this in so stark a contrast to the young man’s liberty, invoking a term quite so strong as ‘imprisoned’ allows at the very least a disquiet about this state of affairs to shine through. Still, it is really no more than a sense we are getting, and we keep having to remind ourselves that our sensitivities may have evolved some distance from where they would have been four hundred years ago in a society that was run as a near absolute monarchy with an almost entirely rigid class system.

The third quatrain though does away with anything resembling subtlety:

Be where you list, your charter is so strong

That you yourself may privilege your time

To what you will: to you it doth belong,

Superficially, there is not much to be argued with that: if the lover is a young nobleman and whether or not he should also happen to be a patron or a potential patron of Shakespeare’s, his charter – as in his right or entitlement – is indeed strong enough that he himself may privilege his own time to what he wants, because to him it does certainly mostly belong. But this is not just a poet speaking to an actual or potential patron, nor just a writer and actor speaking to, in all likelihood, a member of the aristocracy, this is a lover speaking to a lover. And in this constellation the sheer imbalance of power and, more to the point, voluntary commitment and offered care, doesn’t just irk, but it aches.

That said, it is the fourth and last line of the third quatrain and then the closing couplet that blow the lid off this barely contained casket of cavil:

Yourself to pardon of self-doing crime.

I am to wait, though waiting so be hell

Not blame your pleasure, be it ill or well.

‘Crime’ is a strong word, now as it was then. If someone needs to ‘pardon' themselves of ‘self-doing crime’ then that means they are either committing that sort of crime right now, or they are prone or likely to do so in the foreseeable future, or have done so in the more recent past, or quite likely both.

But I, the poet, have just been telling you, my lover, and myself, that it is not for me to even think about what you are up to, let alone criticise you for it. Now throwing into the equation the concept of crime rather undermines this self-sufficient, self-effacing stance and says, you may call it what you want, I still consider it an offence. And all I can do in response is wait, “though waiting so be hell” and not “blame your pleasure, be it” significantly, “ill or well.” This wording too therefore raises not just a remote possibility that something untoward may be going on while you are away from me, but that there is – if this sentence alone is anything to go by – a pretty much equal balance of probabilities of the pleasures you indulge in being ‘ill’ or ‘well’.

That then perhaps still poses the question: what are these ill pleasures? The mind does not need to boggle at this. We know from Sonnets 33 to 42 that this young man – always and still reasonably assuming it is the same young man – has been getting off not with just anybody, but with Shakespeare’s own mistress and there is virtually no strong contender for an ill pleasure other than further sexual encounters, with – as these two poems make clear – whomsoever the young man chooses. Nothing in this couple of poems suggests that this is the same woman as on said previous occasion, and no indication is given as to whether we are even to imagine this person or indeed these people to be male or female or quite possibly of an ambiguous gender.

Nor do we need to wonder and speculate a great deal how William Shakespeare feels about this. He is in hell. He says so. True, he also says that he is not to blame – for which read accuse or even suspect – his lover, but the uncertainty is obviously troubling him a great deal. It may not be killing him: he is alive, but he is barely kicking right now.

And there is an interesting gradient nuance built into the three quatrains of this poem. The first one ends on the word ‘leisure’ to rhyme with ‘pleasure’: nothing particularly noteworthy there and nothing that in and of itself needs to set alarm bells ringing: both the ‘pleasure’ and the ‘leisure’ could still be entirely innocent and quotidian.

The second quatrain ends on the word ‘injury’ to rhyme – not entirely smoothy or purely, it has to be said – with ‘liberty’. And although Shakespeare makes a point of saying that he is not to accuse the young man of ‘injury’, he still pairs the young man’s ‘liberty’ directly with just that: an injury to him, William Shakespeare. That, in and of itself, is telling: were the young man’s ‘liberty’ but the natural sense of freedom that, as Sonnet 41 even then somewhat disingenuously put it, “thy beauty and thy years full well befits,” quite apart from also matching the young man’s evident status, then injury would not come into consideration. There, in Sonnet 41, Shakespeare was quite understandably not happy that the young man’s ‘liberty’ had committed “those pretty wrongs” which were beyond doubt at the time, because they had involved a woman Shakespeare claimed as his.

Here, though, these ‘wrongs’ are no longer ‘pretty’. They are, and this is the extraordinary arc this sonnet spans, ‘self-doing crime’, now in a perfect rhyme with time. To what extent, if any, incidentally, the rhyme alignment is consciously significant we really can’t tell, and so it may be well to exercise a degree of caution here too and not read all too much into this. But the escalation from ‘leisure’ to ‘injury’ to ‘crime’ can hardly be ignored or dismissed: our Will is adding layer onto layer of discomfiture and virtually the only reasonable explanation I can think of for this is that he viscerally feels the pain.

How long this pain lasts and how it will be eased remains to be seen and is not something we can answer in one sentence, or even one paragraph, because what comes next are two reflections on time, both placed in relation to the young man, the first explicitly referring to his beauty, the second more generically to his worth, and then we need to take a step back and look at where we are, because while the series of sonnets continues and does so in a tone and manner that is entirely congruent with what has gone before so far, we need to acknowledge that there is then, after Sonnet 60, a first question mark over the sequence as we know it.

There is a theory that then disrupts the flow of the sonnets and posits a time of composition for the next batch that would place them before the ones we have encountered so far, and it this is a view that is adopted and respected enough among Shakespeare scholars for us to have to take it seriously and examine its plausibility and what it means for our understanding of the sonnets.

What is certain is that we are about to witness an audible key change and enter a phase of sonneteering that shows us a pensive, reflective, philosophical, but also furious and frustrated mind at work whose rage is not just with his lover’s independence, undependability and infidelity, but also with the world he inhabits as a whole. And so if you found anything about William Shakespeare’s sonnets fascinating so far, you are in for a treat, because a lot of the best – as in: most exciting, most thrilling, most extraordinary sonnet composing the English language has ever been gifted – is yet to come…

The two sonnets forming a pair with one coherent argument, here they are back to back, as they belong:

Being your slave, what should I do but tend

Upon the hours and times of your desire?

I have no precious time at all to spend,

Nor services to do, till you require.

Nor dare I chide the world-without-end hour

Whilst I, my sovereign, watch the clock for you,

Nor think the bitterness of absence sour

When you have bid your servant once adieu.

Nor dare I question with my jealous thought

Where you may be, or your affairs suppose,

But like a sad slave stay and think of nought,

Save where you are, how happy you make those.

So true a fool is love that in your will,

Though you do anything, he thinks no ill.

That God forbid that made me first your slave

I should in thought control your times of pleasure,

Or at your hand th'account of hours to crave,

Being your vassal, bound to stay your leisure.

O let me suffer, being at your beck,

Th'imprisoned absence of your liberty,

And, patience-tame to sufferance, bide each check

Without accusing you of injury.

Be where you list, your charter is so strong

That you yourself may privilege your time

To what you will: to you it doth belong,

Yourself to pardon of self-doing crime.

I am to wait, though waiting so be hell,

Not blame your pleasure, be it ill or well.

If Sonnet 57 managed to end on a perhaps resigned but still conciliatory note that acknowledged how great a fool a love such as the one experienced by our poet can make of us, Sonnet 58 deepens the sense of servitude conveyed by Sonnet 57 and at the same time heightens the level of sarcasm we can hear.

As in Sonnet 57, we may need to be somewhat careful in just how much of such self-conscious self-awareness we read into these two sonnets, but while in Sonnet 57 we still felt we had at least a good enough reason to accept the distinct possibility that Shakespeare is in fact being entirely sincere, with Sonnet 58 this becomes increasingly difficult.

The opening salvo itself to us sounds somewhat over the top: “That God forbid!” We still use the expression, but rarely nowadays with innocent sincerity. This is not strictly the case in Shakespeare: as previously observed, he uses the phrase often in his plays and certainly not always – in fact not even predominantly – with irony or let alone sarcasm.

And so it is possible that the first quatrain of Sonnet 58 may well be taken at face value. We have speculated quite extensively by now about the type of person – and sporadically early on also about the identity of the person – these sonnets are addressed to or about and although to us today the notion – outside perhaps some fetish context – that someone would describe themselves as someone else’s ‘vassal’ is somewhat strange at best and absurd at worst, it is entirely possible that Shakespeare genuinely sees himself in relation to the young man as economically dependent, socially inferior, and therefore morally obliged to him.

During the second quatrain, our whispering doubts gain in volume. There is a difference between being someone’s liegeman or vassal who, after all, possesses a certain level of agency and autonomy, and being at someone’s beck, which implies much more the status of a servant or a footman. And then positioning this in so stark a contrast to the young man’s liberty, invoking a term quite so strong as ‘imprisoned’ allows at the very least a disquiet about this state of affairs to shine through. Still, it is really no more than a sense we are getting, and we keep having to remind ourselves that our sensitivities may have evolved some distance from where they would have been four hundred years ago in a society that was run as a near absolute monarchy with an almost entirely rigid class system.

The third quatrain though does away with anything resembling subtlety:

Be where you list, your charter is so strong

That you yourself may privilege your time

To what you will: to you it doth belong,

Superficially, there is not much to be argued with that: if the lover is a young nobleman and whether or not he should also happen to be a patron or a potential patron of Shakespeare’s, his charter – as in his right or entitlement – is indeed strong enough that he himself may privilege his own time to what he wants, because to him it does certainly mostly belong. But this is not just a poet speaking to an actual or potential patron, nor just a writer and actor speaking to, in all likelihood, a member of the aristocracy, this is a lover speaking to a lover. And in this constellation the sheer imbalance of power and, more to the point, voluntary commitment and offered care, doesn’t just irk, but it aches.

That said, it is the fourth and last line of the third quatrain and then the closing couplet that blow the lid off this barely contained casket of cavil:

Yourself to pardon of self-doing crime.

I am to wait, though waiting so be hell

Not blame your pleasure, be it ill or well.

‘Crime’ is a strong word, now as it was then. If someone needs to ‘pardon' themselves of ‘self-doing crime’ then that means they are either committing that sort of crime right now, or they are prone or likely to do so in the foreseeable future, or have done so in the more recent past, or quite likely both.

But I, the poet, have just been telling you, my lover, and myself, that it is not for me to even think about what you are up to, let alone criticise you for it. Now throwing into the equation the concept of crime rather undermines this self-sufficient, self-effacing stance and says, you may call it what you want, I still consider it an offence. And all I can do in response is wait, “though waiting so be hell” and not “blame your pleasure, be it” significantly, “ill or well.” This wording too therefore raises not just a remote possibility that something untoward may be going on while you are away from me, but that there is – if this sentence alone is anything to go by – a pretty much equal balance of probabilities of the pleasures you indulge in being ‘ill’ or ‘well’.

That then perhaps still poses the question: what are these ill pleasures? The mind does not need to boggle at this. We know from Sonnets 33 to 42 that this young man – always and still reasonably assuming it is the same young man – has been getting off not with just anybody, but with Shakespeare’s own mistress and there is virtually no strong contender for an ill pleasure other than further sexual encounters, with – as these two poems make clear – whomsoever the young man chooses. Nothing in this couple of poems suggests that this is the same woman as on said previous occasion, and no indication is given as to whether we are even to imagine this person or indeed these people to be male or female or quite possibly of an ambiguous gender.

Nor do we need to wonder and speculate a great deal how William Shakespeare feels about this. He is in hell. He says so. True, he also says that he is not to blame – for which read accuse or even suspect – his lover, but the uncertainty is obviously troubling him a great deal. It may not be killing him: he is alive, but he is barely kicking right now.

And there is an interesting gradient nuance built into the three quatrains of this poem. The first one ends on the word ‘leisure’ to rhyme with ‘pleasure’: nothing particularly noteworthy there and nothing that in and of itself needs to set alarm bells ringing: both the ‘pleasure’ and the ‘leisure’ could still be entirely innocent and quotidian.

The second quatrain ends on the word ‘injury’ to rhyme – not entirely smoothy or purely, it has to be said – with ‘liberty’. And although Shakespeare makes a point of saying that he is not to accuse the young man of ‘injury’, he still pairs the young man’s ‘liberty’ directly with just that: an injury to him, William Shakespeare. That, in and of itself, is telling: were the young man’s ‘liberty’ but the natural sense of freedom that, as Sonnet 41 even then somewhat disingenuously put it, “thy beauty and thy years full well befits,” quite apart from also matching the young man’s evident status, then injury would not come into consideration. There, in Sonnet 41, Shakespeare was quite understandably not happy that the young man’s ‘liberty’ had committed “those pretty wrongs” which were beyond doubt at the time, because they had involved a woman Shakespeare claimed as his.

Here, though, these ‘wrongs’ are no longer ‘pretty’. They are, and this is the extraordinary arc this sonnet spans, ‘self-doing crime’, now in a perfect rhyme with time. To what extent, if any, incidentally, the rhyme alignment is consciously significant we really can’t tell, and so it may be well to exercise a degree of caution here too and not read all too much into this. But the escalation from ‘leisure’ to ‘injury’ to ‘crime’ can hardly be ignored or dismissed: our Will is adding layer onto layer of discomfiture and virtually the only reasonable explanation I can think of for this is that he viscerally feels the pain.

How long this pain lasts and how it will be eased remains to be seen and is not something we can answer in one sentence, or even one paragraph, because what comes next are two reflections on time, both placed in relation to the young man, the first explicitly referring to his beauty, the second more generically to his worth, and then we need to take a step back and look at where we are, because while the series of sonnets continues and does so in a tone and manner that is entirely congruent with what has gone before so far, we need to acknowledge that there is then, after Sonnet 60, a first question mark over the sequence as we know it.

There is a theory that then disrupts the flow of the sonnets and posits a time of composition for the next batch that would place them before the ones we have encountered so far, and it this is a view that is adopted and respected enough among Shakespeare scholars for us to have to take it seriously and examine its plausibility and what it means for our understanding of the sonnets.

What is certain is that we are about to witness an audible key change and enter a phase of sonneteering that shows us a pensive, reflective, philosophical, but also furious and frustrated mind at work whose rage is not just with his lover’s independence, undependability and infidelity, but also with the world he inhabits as a whole. And so if you found anything about William Shakespeare’s sonnets fascinating so far, you are in for a treat, because a lot of the best – as in: most exciting, most thrilling, most extraordinary sonnet composing the English language has ever been gifted – is yet to come…

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!