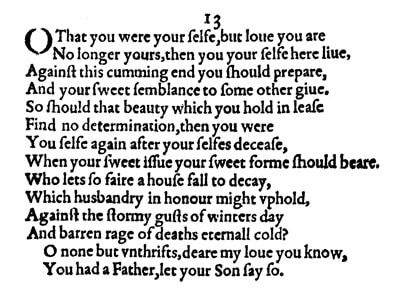

Sonnet 13: O That You Were Yourself, But Love, You Are

|

O that you were yourself, but love, you are

No longer yours than you yourself here live; Against this coming end you should prepare And your sweet semblance to some other give. So should that beauty which you hold in lease Find no determination; then you were Yourself again after your self's decease, When your sweet issue your sweet form should bear. Who lets so fair a house fall to decay, Which husbandry in honour might uphold Against the stormy gusts of winter's day And barren rage of death's eternal cold? O none but unthrifts, dear my love, you know You had a father, let your son say so. |

|

O that you were yourself, but love, you are

No longer yours than you yourself here live; |

O I wish that you could be yourself as you are now forever, but, love, you can no longer be you than you as a person live on this planet.

A dense couple of lines that once again pack a lot into few words. Most taxing for us is the omission of what 'being yourself' here implies, which is being durably in charge of your own destiny. William Shakespeare does not spell this out, but it is nevertheless pretty clear that this is what he means: your existence on earth is delimited to your physical life, and when that comes to an end, you will be gone. |

|

Against this coming end you should prepare

And your sweet semblance to some other give. |

You should prepare yourself for death – "this coming end" – by producing a child.

No surprises here: we are still firmly in the Procreation Sequence, and the way you can give your semblance or likeness to some other person is by making that person, namely a child. Here always, as we have established, a son. |

|

So should that beauty which you hold in lease

|

This way the beauty that you are merely holding onto as a lease or a long-term loan...

This echoes Sonnet 4 where Shakespeare told the young man: "Nature's bequest gives nothing but doth lend." |

|

Find no determination; then you were

Yourself again after your self's decease |

...would be without end: the lease would have no termination date specified, because you would be yourself again even after your own death, in other words, this lease or loan would simply continue...

|

|

When your sweet issue your sweet form should bear.

|

When your lovely child – "your sweet issue" – will have your beautiful looks – "your sweet form should bear."

|

|

Who lets so fair a house fall to decay,

|

Who would let such a beautiful family fall to ruins...

The 'house' here once again, much as the "beauteous roof" of Sonnet 10 stands for a family name, a lineage, and an estate, By not having children, the young man will let this family tree fall to decay, as it will not be renewed but come to an end when he himself dies. |

|

Which husbandry in honour might uphold

|

Which care and attention might honourably maintain and fortify...

The word play on 'husband' is no doubt deliberate. Husbandry is really the care and management of plants and livestock, but also by extension of an estate. We had "the tillage of thy husbandry" in Sonnet 3, where the poet asserted that no woman would be so beautiful as to disdain it from this young man. |

|

Against the stormy gusts of winter's day

And barren rage of death's eternal cold? |

...against the cold winds of winter and the empty rage of death.

One of the most strikingly powerful phrases to appear in these sonnets so far: "the barren rage of death's eternal cold." We are used to think of someone being 'filled with anger' and so the empty, void rage of a cold death is especially evocative. |

|

O none but unthrifts. Dear my love, you know

You had a father. Let your son say so. |

And here comes the answer to that largely rhetorical question: only a wasteful, unthrifty person – "none but unthrifts" – would do so. Again, we have had "unthrifty loveliness" in Sonnet 4 and the charge against the young man of wanton wastefulness is a theme that runs through this early part of the series.

And then the startling personal plea: my dear love, you know you had a father, let your son say so, obviously by producing him in the first place. And we will have a lot more to say about this couple of lines in just a moment... |

The personal, pleading, and particularly revealing Sonnet 13 marks an especially noteworthy change in tone and it provides one specific detail that narrows the field of candidates for the young man dramatically in one fell swoop.

Most immediately noticeable from the outset is the personal pronoun. This is the first sonnet in the series that addresses the young man as 'you'. Up until now, the poet has been addressing the young recipient of these poems as 'thou', which actually is the more familiar form of address that either an older person would use towards a younger one, or someone of higher social status to someone of lower social status, or two friends in a more casual setting to each other, roughly equivalent to the German 'du' or the French 'tu' or the Italian or Spanish 'tu'.

What exactly the significance of this is we do not know, as it is not explained, either in the sonnet itself or elsewhere, and any conclusion we might draw would be pure speculation, but that it is in one way or another of significance offers itself as highly likely, and in the absence of certainty, as we know, likelihood is our friend: I, the poet, William Shakespeare, am surely making a choice here and I am combining this choice with the second most striking feature of this sonnet: the relationship in which I position myself to the young man. Having unequivocally put myself into these sonnets for the first time only very recently with Sonnet 10, where I asked the young man to "make thee another self for love of me," I now go several steps further and call him "love" first, and then, just in case that wasn't quite clear enough, "my love."

There is here, as there was before, a possibility that I am speaking on somebody else's behalf. That I place myself into the shoes of someone who is close enough to the young man to call him "my love," but we have no evidence of this being the case. And in the sequence as it has unfolded so far it does absolutely make sense for me to become yet bolder, more personal, more openly intimate. We have been on a trajectory, not entirely linear, but traceable, from a fairly uninvolved formality to a dismantling of these boundaries, and here now I speak with the voice of someone who knows this young man and cares for him and considers him to be "my love." And that can hardly be meaningless.

It may also quite conceivably be a pointer towards an answer to the question: why use the formal 'you' here? This is somewhat more tentative, but if I am writing to someone whom I am getting to know better and whom I am beginning to have more than just writerly feelings for, and this person is someone of eminently and obviously high social status, which does not, however, keep me from expressing the fact that I am beginning to feel actual personal care and love for this person, then now would not be a bad time to err on the slightly safe side and counterpoint the intimacy of the words with a greater level of formality and respect in the framing of these words. In fact, it would be quite an ingenious way of fending off any potential accusation of overstepping the mark or being way too presumptuous. It would signal: I know my place, but this is how I am starting to feel about you. It would be what a brilliant and daring poet just might do. Again, and to be clear: we don't know if this is what's happening here, whether this is the intention of William Shakespeare at this point. It is merely a possibility that in the context of what we have been seeing so far would make a degree of sense and be therefore quite attractive, and it is something that the words themselves do to a degree suggest. No more, but also no less.

Between the second and the twelfth line of this perfectly well constructed poem nothing occurs that we wouldn't expect or have not seen in one form or another expressed before: you should prepare yourself against your own demise by having a child so you can live on in your child when you die. A slightly new and certainly poetic tone is found with the third quatrain, as we saw in the 'translation' earlier. Shakespeare speaks of the 'barren rage of death's eternal cold'. It's the strongest we've heard him on death, and this will be a recurring theme. We do get a sense, certainly, that the poet knows about death and has experienced the harsh reality of untimely bereavement. And this is not in itself of course unusual: we have noted before how short life and how violent death could be in Elizabethan England. And how little sense a death might make in such a world.

Then, in the thirteenth line of the thirteenth Sonnet: "Dear my love, you know" – the strongest expression of affection yet from me, the poet, to you, the young man, and then a line that like a focus on a photographic lens narrows things down suddenly and substantially: "You know you had a father, let your son say so."

Had. You had a father. Now, people have come up with all kinds of explanations why I, the poet, might here say to you, the young man that you had a father and not that you have a father, but none is as plausible and as obviously fitting as the one that obviously fits: you had a father. He is no more: once he was alive and you quite possibly remember him from your childhood, but now you are fatherless.

Could this be a mistake? An accident? Well, it could. But again: I, William Shakespeare, am the greatest poet ever to have written in the English language: if I felt so inclined I could write a sentence that rhymes and scans and tells the person I am talking to that he has a father. I choose not to do so. In the sonnet where I choose to address the young man with the more formal 'you' while at the same time calling him 'my dear love' I also choose to remind him that he had a father. It would be an insult supreme to use the past tense here if the young man's father were alive and well. And it would not make sense to bury any hidden message in this, not least because it would be so insulting. So there can hardly be any genuinely justified question as to whether this is deliberate and meaningful. Of course it is. I could have written: Dear my love, you know you have a father, let your son say so. The poem would work almost as well. Even for the slight nuance that it doesn't, I could make the line work for me and for the young man if the young man actual still had a father, if I so wished. I did not. And from a fellow writer's perspective, it is preposterous and patronising in the extreme to be told I may just have made a minor mistake here.

And we don't have to leave it there. What makes the argument for this being a direct and significant pointer towards the identity of the young man even more compelling is that it doesn't stand alone. In Sonnet 3 we wondered about the reasons why William Shakespeare is making such a deliberate point about the resemblance the young man bears to his mother. Not his father. And we thought there were three possible reasons: a) he really bears a striking resemblance to his mother, b) his father isn't around to be compared to, or c) possibly both.

Here now we have "you had a father." It tallies up directly. And, granted, it would perhaps still potentially appear a little far-fetched to imagine that there is a young English nobleman in his late teens or early twenties who is obstinate in his refusal to marry, who is either a first born or an only son, who bears a striking resemblance not to his father but to his mother, and whose father in any case is no longer alive, were it not for the fact that there is such a young man to whom absolutely all of the above applies.

We are not going to name him, not yet. Why? Because while it would no longer seem quite so premature now, seeing that the evidence is coming together bit by bit, it would still be a step too far too soon. We will get there, do not worry. We will discuss the potential candidates for the young man and we will be able to make some fairly well-informed choices about whom to allow and whom to dismiss as likely contenders. But doing so is a big deal: scholars have speculated, argued, even fought, over this question for four centuries now and there is no incontrovertible truth. There is no hard evidence that amounts to incontestable proof. And so this question of who the young man who receives these sonnets is merits a great deal of diligence and care when we come to it. And, indeed, its own episode. Before then though – most fortuitously – there will be quite a few more pointers and more evidence to gather...

Most immediately noticeable from the outset is the personal pronoun. This is the first sonnet in the series that addresses the young man as 'you'. Up until now, the poet has been addressing the young recipient of these poems as 'thou', which actually is the more familiar form of address that either an older person would use towards a younger one, or someone of higher social status to someone of lower social status, or two friends in a more casual setting to each other, roughly equivalent to the German 'du' or the French 'tu' or the Italian or Spanish 'tu'.

What exactly the significance of this is we do not know, as it is not explained, either in the sonnet itself or elsewhere, and any conclusion we might draw would be pure speculation, but that it is in one way or another of significance offers itself as highly likely, and in the absence of certainty, as we know, likelihood is our friend: I, the poet, William Shakespeare, am surely making a choice here and I am combining this choice with the second most striking feature of this sonnet: the relationship in which I position myself to the young man. Having unequivocally put myself into these sonnets for the first time only very recently with Sonnet 10, where I asked the young man to "make thee another self for love of me," I now go several steps further and call him "love" first, and then, just in case that wasn't quite clear enough, "my love."

There is here, as there was before, a possibility that I am speaking on somebody else's behalf. That I place myself into the shoes of someone who is close enough to the young man to call him "my love," but we have no evidence of this being the case. And in the sequence as it has unfolded so far it does absolutely make sense for me to become yet bolder, more personal, more openly intimate. We have been on a trajectory, not entirely linear, but traceable, from a fairly uninvolved formality to a dismantling of these boundaries, and here now I speak with the voice of someone who knows this young man and cares for him and considers him to be "my love." And that can hardly be meaningless.

It may also quite conceivably be a pointer towards an answer to the question: why use the formal 'you' here? This is somewhat more tentative, but if I am writing to someone whom I am getting to know better and whom I am beginning to have more than just writerly feelings for, and this person is someone of eminently and obviously high social status, which does not, however, keep me from expressing the fact that I am beginning to feel actual personal care and love for this person, then now would not be a bad time to err on the slightly safe side and counterpoint the intimacy of the words with a greater level of formality and respect in the framing of these words. In fact, it would be quite an ingenious way of fending off any potential accusation of overstepping the mark or being way too presumptuous. It would signal: I know my place, but this is how I am starting to feel about you. It would be what a brilliant and daring poet just might do. Again, and to be clear: we don't know if this is what's happening here, whether this is the intention of William Shakespeare at this point. It is merely a possibility that in the context of what we have been seeing so far would make a degree of sense and be therefore quite attractive, and it is something that the words themselves do to a degree suggest. No more, but also no less.

Between the second and the twelfth line of this perfectly well constructed poem nothing occurs that we wouldn't expect or have not seen in one form or another expressed before: you should prepare yourself against your own demise by having a child so you can live on in your child when you die. A slightly new and certainly poetic tone is found with the third quatrain, as we saw in the 'translation' earlier. Shakespeare speaks of the 'barren rage of death's eternal cold'. It's the strongest we've heard him on death, and this will be a recurring theme. We do get a sense, certainly, that the poet knows about death and has experienced the harsh reality of untimely bereavement. And this is not in itself of course unusual: we have noted before how short life and how violent death could be in Elizabethan England. And how little sense a death might make in such a world.

Then, in the thirteenth line of the thirteenth Sonnet: "Dear my love, you know" – the strongest expression of affection yet from me, the poet, to you, the young man, and then a line that like a focus on a photographic lens narrows things down suddenly and substantially: "You know you had a father, let your son say so."

Had. You had a father. Now, people have come up with all kinds of explanations why I, the poet, might here say to you, the young man that you had a father and not that you have a father, but none is as plausible and as obviously fitting as the one that obviously fits: you had a father. He is no more: once he was alive and you quite possibly remember him from your childhood, but now you are fatherless.

Could this be a mistake? An accident? Well, it could. But again: I, William Shakespeare, am the greatest poet ever to have written in the English language: if I felt so inclined I could write a sentence that rhymes and scans and tells the person I am talking to that he has a father. I choose not to do so. In the sonnet where I choose to address the young man with the more formal 'you' while at the same time calling him 'my dear love' I also choose to remind him that he had a father. It would be an insult supreme to use the past tense here if the young man's father were alive and well. And it would not make sense to bury any hidden message in this, not least because it would be so insulting. So there can hardly be any genuinely justified question as to whether this is deliberate and meaningful. Of course it is. I could have written: Dear my love, you know you have a father, let your son say so. The poem would work almost as well. Even for the slight nuance that it doesn't, I could make the line work for me and for the young man if the young man actual still had a father, if I so wished. I did not. And from a fellow writer's perspective, it is preposterous and patronising in the extreme to be told I may just have made a minor mistake here.

And we don't have to leave it there. What makes the argument for this being a direct and significant pointer towards the identity of the young man even more compelling is that it doesn't stand alone. In Sonnet 3 we wondered about the reasons why William Shakespeare is making such a deliberate point about the resemblance the young man bears to his mother. Not his father. And we thought there were three possible reasons: a) he really bears a striking resemblance to his mother, b) his father isn't around to be compared to, or c) possibly both.

Here now we have "you had a father." It tallies up directly. And, granted, it would perhaps still potentially appear a little far-fetched to imagine that there is a young English nobleman in his late teens or early twenties who is obstinate in his refusal to marry, who is either a first born or an only son, who bears a striking resemblance not to his father but to his mother, and whose father in any case is no longer alive, were it not for the fact that there is such a young man to whom absolutely all of the above applies.

We are not going to name him, not yet. Why? Because while it would no longer seem quite so premature now, seeing that the evidence is coming together bit by bit, it would still be a step too far too soon. We will get there, do not worry. We will discuss the potential candidates for the young man and we will be able to make some fairly well-informed choices about whom to allow and whom to dismiss as likely contenders. But doing so is a big deal: scholars have speculated, argued, even fought, over this question for four centuries now and there is no incontrovertible truth. There is no hard evidence that amounts to incontestable proof. And so this question of who the young man who receives these sonnets is merits a great deal of diligence and care when we come to it. And, indeed, its own episode. Before then though – most fortuitously – there will be quite a few more pointers and more evidence to gather...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!