Sonnet 16: But Wherefore Do Not You a Mightier Way

|

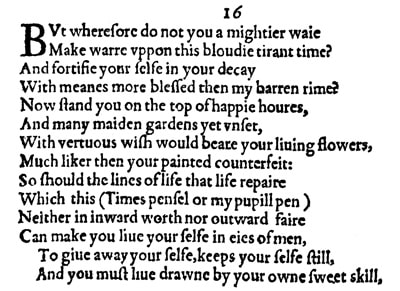

But wherefore do not you a mightier way

Make war upon this bloody tyrant Time, And fortify yourself in your decay With means more blessed than my barren rhyme? Now stand you on the top of happy hours, And many maiden gardens, yet unset, With virtuous wish would bear your living flowers, Much liker than your painted counterfeit; So should the lines of life that life repair Which this, Time's pencil, or my pupil pen, Neither in inward worth nor outward fair Can make you live yourself in eyes of men. To give away yourself keeps yourself still, And you must live, drawn by your own sweet skill. |

|

But wherefore do not you a mightier way

Make war upon this bloody tyrant Time, |

At the end of Sonnet 15, I, William Shakespeare, tell the young man that I am in a war with Time for the love of you, and that I – by implication using my pen as a poet – engraft you new as he, Time, hastens your decay. Here now, I continue:

But why do you not use a more powerful way than the one I have just described in the previous sonnet to fight your war against this bloody tyrant Time... |

|

And fortify yourself in your decay

With means more blessed than my barren rhyme. |

...and fortify yourself against this decay with means that are more likely to succeed than these empty verses that I am writing for you.

The barrenness or emptiness of the verses most likely refers to their potency rather than their intention and very soon we will come upon two instances where Shakespeare considers his rhyme anything but barren. |

|

Now stand you on the top of happy hours,

|

Now you are at the height of your powers, your beauty, your status...

|

|

And many maiden gardens yet unset

With virtuous wish would bear your living flowers |

And many a young woman who is as yet a virgin would virtuously wish to bear your metaphorical flowers, meaning your children.

In Sonnet 3 Shakespeare asked the young man rhetorically: "For where is she, so fair, whose uneared womb disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?" This in tone and imagery is similar. The potential prospective mother is likened to an as yet unseeded garden which is ready for beautiful flowers to be planted there. And here again it is stated as obvious that there are any number of women who would want this to happen, by this particular young man. |

|

Much liker than your painted counterfeit.

|

Your 'living flowers' – your children – would look much more like you than any painting of you.

There may be a double meaning intended that also says: they, the virginal maidens would much prefer to receive a child from you than a painting, they would 'like' this much more. It was not unusual at all at the time for lovers or the betrothed to give, receive and then keep lockets with pictures of each other. 'Counterfeit' here simply means a copy of the original, not necessarily one made to deceive anyone, although a suggestion that any painting of the young man would not be able to do justice to its original is very likely intended. Interestingly, paintings as a means to preserve the young man's beauty have not really entered the discussion before and so we will look into this a bit further shortly. |

|

So should the lines of life that life repair

|

In this manner the continuing line of life, your lineage, will be able to keep up and restore to you to your erstwhile beauty...

We've already had 'repair' to mean 'maintain' and 'keep in good order and shape' before, in Sonnet 10, where Shakespeare tells the young man that "to repair" his "house" should be his "chief desire." |

|

Which this, Time's pencil or my pupil pen,

|

...which this, what I have been talking about, the metaphorical pencil of Time and my unschooled, inadequate writing...

We will come to the surprising appearance of "Time's pencil" in a moment, as it merits a bit of further consideration. |

|

Neither in inward worth nor outward fair

|

...neither in terms of your inner worth or substance nor of your outward beauty...

|

|

Can make you live yourself in eyes of men.

|

...can do you justice and represent you as you really are – live yourself – for everyone to see – in eyes of men.

|

|

To give away yourself keeps yourself still,

|

Giving yourself away, here specifically as in marrying someone with the expected and fully intended giving of yourself in the act of producing a child, maintains you forever or certainly for the foreseeable future...

Shakespeare uses 'still' to mean 'continuously' every so often. |

|

And you must live, drawn by your own sweet skill.

|

And you must continue to live, drawn not by an artist, or by Time's pencil, which we'll come to, nor by my words, which are all inadequate, but by your own beautiful art.

This "sweet skill" may be read quite abstractly as the young man metaphorically painting an image of himself by fathering a child; knowing Shakespeare though it very likely is also a description of the act of fathering itself: the poet has by now, we are aware, developed a soft spot for the young man, and while there is absolutely no indication as yet that they have become close, let alone intimate, it is far from implausible that Shakespeare is describing the young man's sexual skills as 'sweet' to mean essentially good and roundly enjoyable. |

The riveting and really rather irony-infused Sonnet 16 directly follows on from Sonnet 15 and completes the argument set up and semi-resolved there. And while Sonnet 15 can just about stand on its own – with, as we have seen – quite thrilling significance for how it then can be read, Sonnet 16 absolutely needs to be read with Sonnet 15 for it to make sense:

When I consider every thing that grows,

Holds in perfection but a little moment;

That this huge stage presenteth nought but shows

Whereon the stars in secret influence comment;

When I perceive that men as plants increase,

Cheered and checked, even by the self-same sky,

Vaunt in their youthful sap, at height decrease,

And wear their brave state out of memory;

Then the conceit of this inconstant stay

Sets you most rich in youth before my sight,

Where wasteful Time debateth with decay

To change your day of youth to sullied night,

And all in war with Time for love of you,

As he takes from you, I engraft you new.

But wherefore do not you a mightier way

Make war upon this bloody tyrant Time,

And fortify yourself in your decay

With means more blessed than my barren rhyme?

Now stand you on the top of happy hours,

And many maiden gardens, yet unset,

With virtuous wish would bear your living flowers,

Much liker than your painted counterfeit;

So should the lines of life that life repair

Which this, Time's pencil, or my pupil pen,

Neither in inward worth nor outward fair

Can make you live yourself in eyes of men.

To give away yourself keeps yourself still,

And you must live, drawn by your own sweet skill.

If there was any suggestion in Sonnet 15 that the poet could offer the young man an alternative to sexual propagation, this here now is slammed down rather forcefully. Whence stems the impression that William Shakespeare may be being somewhat ironic.

That he doesn't really think his rhyme is barren is already fairly clear from the way he celebrates, deploys and elevates it, and we are only two sonnets away from the most astonishing assertion of a poet's output's longevity, so we get an early indication in this Sonnet 16 that perhaps the poet isn't being altogether sincere now with this second half of his argument. And then listen to how he continues. "Now stand you on the top of happy hours:" that is certainly the case, as most likely is the assumption that the young man would have his pick of potential brides if he were inclined to choose one. But then, effectively out of nowhere, comes the notion of a painted counterfeit, and the somewhat perplexing idea of Time having or using a pencil to draw the young man.

Why is this perplexing? The lines that Time draws – as Sonnet 2 made abundantly clear and as Sonnet 19 will strongly reinforce – are those of age. They are the traces of Time's own passing. Time's pencil, if we want to think of Time as an artist, is not one that preserves us in our youth, it is one that gradually ages us. This creates a number of complications for our Sonnet 16 here. The fact that Shakespeare introduces the painting as a possible way of preserving someone's good looks is not particularly upsetting: although it has nothing to do with anything that's been said before, we may as well simply accept this at face value and say: true, in an age where people are known to give each other lockets with paintings of themselves it makes sense to say that a young woman would prefer to have a young man's child than just his picture. The child would be more like the young father than any picture could ever be, and the joy all round would be infinitely greater.

It also then makes sense to say that compared to the lines drawn by an artist the lines of life are bound to be more successful at keeping the young man 'alive' and his life in 'good repair'. So far, still, so good. What though of Time's pencil? Are we to read this as simply a mistake on the part of the poet? Or are we misunderstanding him, and is he talking about the enduring pencil of a timeless artist in some way? Or is he, as some editors suggest, talking about today's pencil – the way an artist depicts you today when you are young – that is capable of maintaining your youth? This would make it necessary to completely ignore the brackets that the typesetter of the Quarto Edition has put around "Time's pencil and my pupil pen." And it is, as we know, entirely possible that they were put there in error and that Shakespeare never had them on his manuscript page, but even though brackets appear every now and then in the sonnets' original publication, they are still comparatively rare and quite specific. They are far less likely to be used mistakenly than a comma, for example.

What is going on here? We simply don't know. What we do know is that halfway through Sonnet 16, Shakespeare does not strictly, certainly not obviously, make sense. And that is quite rare for a wordsmith as capable and as inventive as Shakespeare. It could well be that he has fallen to victim to somebody else's mishap along the way, such as a typesetter's, and that these lines once made perfect sense; it is also possible that we are missing a contemporary reference that would have made it crystal clear to the young man when to us it is murky. Or it could be the case that Shakespeare is giving up on his task. He just doesn't particularly care about the maiden gardens and the ensuing offspring anymore because he has cottoned on to a completely different and for him much more exciting idea: that he can give the young man eternal youth and life beyond death.

And so, similarly, this "pupil pen" so referred here, is surely not sincere. Surely what Shakespeare is saying here is simply: you know and I know that we're done with pretending that I want you to marry right now. Because what I am about to write are going to be sonnets like you've never heard or read before, and there will be dozens upon dozens of them.

That said, he does bring the sonnet to a meaningful conclusion. And herein too may lie a 'message' to the young man. This final couplet can so easily, so readily be read on two levels at least. Either in the context of the procreation line of argument: giving yourself to someone else in matrimonial union and making a child continues your lineage, and you must do this yourself, using your own "sweet skill." Or at a higher, for want of a better word Platonic level: giving yourself away in love and friendship to another person – such as me – will keep you alive and young, and you have to use your own judgement, your own understanding, your own 'life skill' to do this and to lead your life.

One thing is for certain: the poet, William Shakespeare, and the young man are now, if not in a relationship then in a constellation that is directly and unambiguously involved: I, the poet, "engraft" you new, I the poet, have ways to keep you alive. Whatever you choose to do, there is an alternative to the way I have been imploring you to adopt all the way through until now.

And this alternative is just about to explode into exquisite, glorious life...

When I consider every thing that grows,

Holds in perfection but a little moment;

That this huge stage presenteth nought but shows

Whereon the stars in secret influence comment;

When I perceive that men as plants increase,

Cheered and checked, even by the self-same sky,

Vaunt in their youthful sap, at height decrease,

And wear their brave state out of memory;

Then the conceit of this inconstant stay

Sets you most rich in youth before my sight,

Where wasteful Time debateth with decay

To change your day of youth to sullied night,

And all in war with Time for love of you,

As he takes from you, I engraft you new.

But wherefore do not you a mightier way

Make war upon this bloody tyrant Time,

And fortify yourself in your decay

With means more blessed than my barren rhyme?

Now stand you on the top of happy hours,

And many maiden gardens, yet unset,

With virtuous wish would bear your living flowers,

Much liker than your painted counterfeit;

So should the lines of life that life repair

Which this, Time's pencil, or my pupil pen,

Neither in inward worth nor outward fair

Can make you live yourself in eyes of men.

To give away yourself keeps yourself still,

And you must live, drawn by your own sweet skill.

If there was any suggestion in Sonnet 15 that the poet could offer the young man an alternative to sexual propagation, this here now is slammed down rather forcefully. Whence stems the impression that William Shakespeare may be being somewhat ironic.

That he doesn't really think his rhyme is barren is already fairly clear from the way he celebrates, deploys and elevates it, and we are only two sonnets away from the most astonishing assertion of a poet's output's longevity, so we get an early indication in this Sonnet 16 that perhaps the poet isn't being altogether sincere now with this second half of his argument. And then listen to how he continues. "Now stand you on the top of happy hours:" that is certainly the case, as most likely is the assumption that the young man would have his pick of potential brides if he were inclined to choose one. But then, effectively out of nowhere, comes the notion of a painted counterfeit, and the somewhat perplexing idea of Time having or using a pencil to draw the young man.

Why is this perplexing? The lines that Time draws – as Sonnet 2 made abundantly clear and as Sonnet 19 will strongly reinforce – are those of age. They are the traces of Time's own passing. Time's pencil, if we want to think of Time as an artist, is not one that preserves us in our youth, it is one that gradually ages us. This creates a number of complications for our Sonnet 16 here. The fact that Shakespeare introduces the painting as a possible way of preserving someone's good looks is not particularly upsetting: although it has nothing to do with anything that's been said before, we may as well simply accept this at face value and say: true, in an age where people are known to give each other lockets with paintings of themselves it makes sense to say that a young woman would prefer to have a young man's child than just his picture. The child would be more like the young father than any picture could ever be, and the joy all round would be infinitely greater.

It also then makes sense to say that compared to the lines drawn by an artist the lines of life are bound to be more successful at keeping the young man 'alive' and his life in 'good repair'. So far, still, so good. What though of Time's pencil? Are we to read this as simply a mistake on the part of the poet? Or are we misunderstanding him, and is he talking about the enduring pencil of a timeless artist in some way? Or is he, as some editors suggest, talking about today's pencil – the way an artist depicts you today when you are young – that is capable of maintaining your youth? This would make it necessary to completely ignore the brackets that the typesetter of the Quarto Edition has put around "Time's pencil and my pupil pen." And it is, as we know, entirely possible that they were put there in error and that Shakespeare never had them on his manuscript page, but even though brackets appear every now and then in the sonnets' original publication, they are still comparatively rare and quite specific. They are far less likely to be used mistakenly than a comma, for example.

What is going on here? We simply don't know. What we do know is that halfway through Sonnet 16, Shakespeare does not strictly, certainly not obviously, make sense. And that is quite rare for a wordsmith as capable and as inventive as Shakespeare. It could well be that he has fallen to victim to somebody else's mishap along the way, such as a typesetter's, and that these lines once made perfect sense; it is also possible that we are missing a contemporary reference that would have made it crystal clear to the young man when to us it is murky. Or it could be the case that Shakespeare is giving up on his task. He just doesn't particularly care about the maiden gardens and the ensuing offspring anymore because he has cottoned on to a completely different and for him much more exciting idea: that he can give the young man eternal youth and life beyond death.

And so, similarly, this "pupil pen" so referred here, is surely not sincere. Surely what Shakespeare is saying here is simply: you know and I know that we're done with pretending that I want you to marry right now. Because what I am about to write are going to be sonnets like you've never heard or read before, and there will be dozens upon dozens of them.

That said, he does bring the sonnet to a meaningful conclusion. And herein too may lie a 'message' to the young man. This final couplet can so easily, so readily be read on two levels at least. Either in the context of the procreation line of argument: giving yourself to someone else in matrimonial union and making a child continues your lineage, and you must do this yourself, using your own "sweet skill." Or at a higher, for want of a better word Platonic level: giving yourself away in love and friendship to another person – such as me – will keep you alive and young, and you have to use your own judgement, your own understanding, your own 'life skill' to do this and to lead your life.

One thing is for certain: the poet, William Shakespeare, and the young man are now, if not in a relationship then in a constellation that is directly and unambiguously involved: I, the poet, "engraft" you new, I the poet, have ways to keep you alive. Whatever you choose to do, there is an alternative to the way I have been imploring you to adopt all the way through until now.

And this alternative is just about to explode into exquisite, glorious life...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!