Sonnet 4: Unthrifty Loveliness, Why Dost Thou Spend

|

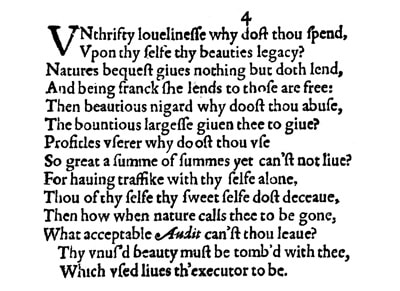

Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spend

Upon thyself thy beauty's legacy? Nature's bequest gives nothing, but doth lend, And being frank she lends to those are free. Then, beauteous niggard, why dost thou abuse The bounteous largesse given thee to give? Profitless usurer, why dost thou use So great a sum of sums, yet canst not live? For, having traffic with thyself alone, Thou of thyself thy sweet self dost deceive; Then how, when nature calls thee to be gone, What acceptable audit canst thou leave? Thy unused beauty must be tombed with thee, Which used lives, th'executor to be. |

|

Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spend

Upon thyself thy beauty's legacy? |

Picking up on the expression 'thriftless praise' in Sonnet 2, Shakespeare calls the young man an 'unthrifty loveliness' – a lovely but wasteful person – and asks him why he spends the legacy of his beauty on himself.

This once again may be quite suggestive. The legacy of the young man's beauty is his children, and so spending this on himself would imply that the young man wastes his potential for producing children – at its most basic his sperm – on himself. |

|

Nature's bequest gives nothing but doth lend

|

The bequest of nature here is beauty: nature has bequeathed on the young man his good looks, but these are not given to him to keep – "gives nothing" – but lent to him, to have for a while and then pass on – "but doth lend."

|

|

And being frank she lends to those are free.

|

And Nature – here, incidentally, we once again have a personification, this time of nature – being 'frank', which here means generous, herself, lends to people who are 'free', which here also means generous. In other words, Nature has an abundance of beauty to lend, and generous as she is, she lends this abundant beauty to those who are, like her, generous.

|

|

Then, beauteous niggard, why dost thou abuse

The bounteous largesse given thee to give? |

Shakespeare picks up on something he has said in Sonnet 1, where he told the young man "thou ... makest waste in niggarding" – you are being wasteful with your procreating potential by being miserly. Remember that a 'niggard', with a D at the end, is a miser. This is not a racial slur, it's an old English word for a person who is ungenerous.

And so here now Shakespeare calls the young man a "beauteous niggard" – a beautiful miser – and asks him why he abuses the plentiful generousness that has been given to him to give away again: "The bounteous largesse given thee to give." Most editors spell out the word 'given' as it is in the Quarto Edition, but for the line to scan we really need to pronounce the word with one syllable. Shakespeare does this very often: 'even', 'heaven', and 'given' are sometimes placed such that they are pronounced as spelt, with two syllables, and quite frequently also such that they are pronounced with one syllable: e'en, hea'en, gi'en. Therefore: PRONUNCIATION: Note that given here is pronounced as one syllable: gi'en. |

|

Profitless usurer, why dost thou use

So great a sum of sums, yet canst not live? |

Usury – the lending of money against interest – in Shakespeare's day is still widely considered a sin although it just around then has recently ceased to be illegal.

Here he calls the young man a 'profitless usurer', meaning somebody who, although he 'lends' something, cannot make a profit from it, and asks him why he uses 'so great a sum of sums' – so much of what he has, which is his beauty and again of course by implication his potential to perpetuate this beauty – and yet cannot live, meaning cannot live on, forever. |

|

For, having traffic with thyself alone,

Thou of thyself thy sweet self dost deceive; |

And here comes the reason why the young man cannot live on forever: because "having traffic with thyself alone" – not entering an exchange with anybody else, here by implication a woman who through this exchange could give him a child – he 'deceives', meaning deprives, himself of himself. In other words, by keeping himself to himself and not sharing himself with somebody else - specifically a potential mother of his child – he is in fact depriving himself of himself...

|

|

Then how, when Nature calls thee to be gone,

What acceptable audit canst thou leave? |

...because he has nothing to leave behind when Nature calls him away, when his death comes.

This is the principal argument that runs through all these first seventeen sonnets: that by not having children the young man, when he dies, will not leave a legacy. His beauty, his name, his line will cease to exist. Small detail here: the 'how' in "Then how, when Nature calls thee to be gone" isn't strictly necessary semantically; the sentence would make sense if it simply read: 'then, when Nature calls thee to be gone," but Shakespeare puts it here for the line to scan as an iambic pentameter. Almost – though not quite – all of these sonnets are written in the iambic pentameter which is absolutely Shakespeare's preferred meter: five pairs of syllables that create a rhythm that goes tadam, tadam, tadam, tadam, tadam, occasionally with an eleventh syllable, though not in this particular sonnet. For the same reason 'acceptable' needs to be stressed on the first syllable, not as we would do in contemporary English, on the second. And an 'acceptable audit' simply means an account – therefore by implication also legacy – of your life that is sufficient and therefore acceptable. |

|

Thy unused beauty must be tombed with thee,

Which used lives th'executor to be. |

Your beauty, if you don't use it to produce a child, will have to be buried – 'tombed' – with you when you die, whereas if you do use it – 'which used' – to produce a child, it then lives on in your child and thus becomes the executor of your legacy: any son of yours would continue your line, your name and your beauty and in doing so metaphorically speaking execute your will.

PRONUNCIATION: Note that used here has two syllables: u-sèd. |

The argument of Sonnet 4 is much the same as that of the first three sonnets: the poet, William Shakespeare, tells the young man – about whom we still don't know very much – that he needs to produce an heir. The analogy the poet uses is perhaps not the most poetic one, and compared to the "forty winters" that "besiege thy brow" and the "deep trenches in thy beauty's field" of Sonnet 2, the legalese of Sonnet 4 may strike us almost a tad pedestrian.

The sonnet's principal tenet is that your beauty is not so much a gift of nature, as it is a loan. And being 'given' — as in 'lent' — so generously by nature, you, the young man, should share this beauty with commensurate generosity with the world by passing it on to future generations. Being mean and selfish with your beauty puts you on a hiding to nothing, because this way, when your day of reckoning comes as you die, you will leave nothing behind that amounts to anything, whereas if you use your beauty to the end of passing it on, you will leave behind a proper legacy.

The sonnet then does not really tell us anything new, nor does it tell the young man whom it is addressed to anything he doesn't already know. And while poetry may be a matter of taste, few people would argue that this is an especially evocative, lyrical or, for want of a better word, 'beautiful' poem.

Which automatically begs the question: if that's the case, why write it? Why is Shakespeare writing a slightly convoluted and certainly fairly dry argument to make a point he has already made three times in more imaginative language and that is really easy to get? And while we don't know the answer to this question, the fact alone that the question seems to be justified opens up a view on an as yet unsubstantiated but plausible possibility: it is far too early to make a call on this, but in the context of the previous three sonnets it does rather seem like Shakespeare simply had to write this poem because somebody asked him to. We don't know if this is the case and we certainly don't know who, if anybody, asked Shakespeare to write this and the other poems in this part of the collection, and what put them into a position to do so. All we do know is that the poet – far from deploying writerly fireworks – is here carefully constructing a fairly abstract and yet still not entirely convincing case in the language of financial and legal affairs to support an argument he has already won with much simpler and more compelling imagery.

This though in itself does not need to entirely surprise us: marriage was very much a legal and financial affair; the vast majority of marriages in Shakespeare's day were entered into not for love or as romantic adventures, but for the sake of an arrangement that benefited both parties, with the parties being the families and estates on either side of the deal, much more than the individuals principally involved in the marriage themselves.

And here perhaps lies the real interest of this Sonnet No 4: not so much in its linguistic dexterity or in the imagery it conjures up – other sonnets in the collection are much more powerful in that regard – but in the atmosphere it conveys of what all this is really about: a transaction. And in this it may well also echo the cause for its own existence: a transaction. It is entirely possible, though entirely unproven, that this sonnet, along with some, all, or most of the first seventeen that make up the Procreation Sequence, was commissioned from the poet purely for the purpose that is so obvious: a young man needs to get on with it and produce an heir.

And when we speak of transactions here, we may include in these those that are of a sexual nature too. Shakespeare comes extremely close to telling the young man in these first few sonnets that he should stop abusing himself and impregnate a woman instead. It sounds crude to put it in these terms, but that is effectively what he does, and Shakespeare elsewhere in his works does not shy away from being bawdy. This, too, need not surprise us: the world William Shakespeare and the young man live in is a visceral, fast-living, immediate one. People live in close connection to the cycles of life; having children is part of a survival strategy for most, and making them is part of nature. There is very little privacy. If you are poor you live in crowded shared accommodation, if you are rich you are almost by definition a public figure.

We have had an inkling, in Sonnet 2, that the young man is well to do, that he is a man of importance and thus "gazed on." We learnt from Sonnet 3 that he bears a striking resemblance to his mother, striking enough at any rate for the poet to point it out in preference to painting a picture of a young man who takes after his father; and we can accept it as an established given that in order for the young man's procreation to be of such great significance as is suggested in these poems, he not only has to be a person of some status and therefore significance himself, but also that the continuation of his line and therefore name really depends largely, so as not to say entirely – although very likely that too – on him, which would make him a firstborn or only son.

And while we don't know very much at all about the relationship, such as it is, between the young man and the poet yet, we get a sense from the tone of Sonnet 4 that we are in something of a transactional setting; an impression that is somewhat supported by the absence of any real emotion or personal investment in these first few poems: I the poet, William Shakespeare, do call the young man a number of paradoxical things, such as a "beauteous niggard," or an "unthrifty loveliness," but these are fairly generic terms that any poet could write about any person of whom one or two basic things are known, in this instance namely that they are beautiful and that they are not purposeful enough in the pursuit of the perpetuation of their lineage.

In other words, apart from the few things we now know about Shakespeare and the young man from just these sonnets, we also know that there are quite a few things we actually genuinely don't know. And this, though it may not at first glance seem so, is itself tremendously exciting and very useful indeed, because once you know what you don't know, you may know what to look for in the things you do know...

The sonnet's principal tenet is that your beauty is not so much a gift of nature, as it is a loan. And being 'given' — as in 'lent' — so generously by nature, you, the young man, should share this beauty with commensurate generosity with the world by passing it on to future generations. Being mean and selfish with your beauty puts you on a hiding to nothing, because this way, when your day of reckoning comes as you die, you will leave nothing behind that amounts to anything, whereas if you use your beauty to the end of passing it on, you will leave behind a proper legacy.

The sonnet then does not really tell us anything new, nor does it tell the young man whom it is addressed to anything he doesn't already know. And while poetry may be a matter of taste, few people would argue that this is an especially evocative, lyrical or, for want of a better word, 'beautiful' poem.

Which automatically begs the question: if that's the case, why write it? Why is Shakespeare writing a slightly convoluted and certainly fairly dry argument to make a point he has already made three times in more imaginative language and that is really easy to get? And while we don't know the answer to this question, the fact alone that the question seems to be justified opens up a view on an as yet unsubstantiated but plausible possibility: it is far too early to make a call on this, but in the context of the previous three sonnets it does rather seem like Shakespeare simply had to write this poem because somebody asked him to. We don't know if this is the case and we certainly don't know who, if anybody, asked Shakespeare to write this and the other poems in this part of the collection, and what put them into a position to do so. All we do know is that the poet – far from deploying writerly fireworks – is here carefully constructing a fairly abstract and yet still not entirely convincing case in the language of financial and legal affairs to support an argument he has already won with much simpler and more compelling imagery.

This though in itself does not need to entirely surprise us: marriage was very much a legal and financial affair; the vast majority of marriages in Shakespeare's day were entered into not for love or as romantic adventures, but for the sake of an arrangement that benefited both parties, with the parties being the families and estates on either side of the deal, much more than the individuals principally involved in the marriage themselves.

And here perhaps lies the real interest of this Sonnet No 4: not so much in its linguistic dexterity or in the imagery it conjures up – other sonnets in the collection are much more powerful in that regard – but in the atmosphere it conveys of what all this is really about: a transaction. And in this it may well also echo the cause for its own existence: a transaction. It is entirely possible, though entirely unproven, that this sonnet, along with some, all, or most of the first seventeen that make up the Procreation Sequence, was commissioned from the poet purely for the purpose that is so obvious: a young man needs to get on with it and produce an heir.

And when we speak of transactions here, we may include in these those that are of a sexual nature too. Shakespeare comes extremely close to telling the young man in these first few sonnets that he should stop abusing himself and impregnate a woman instead. It sounds crude to put it in these terms, but that is effectively what he does, and Shakespeare elsewhere in his works does not shy away from being bawdy. This, too, need not surprise us: the world William Shakespeare and the young man live in is a visceral, fast-living, immediate one. People live in close connection to the cycles of life; having children is part of a survival strategy for most, and making them is part of nature. There is very little privacy. If you are poor you live in crowded shared accommodation, if you are rich you are almost by definition a public figure.

We have had an inkling, in Sonnet 2, that the young man is well to do, that he is a man of importance and thus "gazed on." We learnt from Sonnet 3 that he bears a striking resemblance to his mother, striking enough at any rate for the poet to point it out in preference to painting a picture of a young man who takes after his father; and we can accept it as an established given that in order for the young man's procreation to be of such great significance as is suggested in these poems, he not only has to be a person of some status and therefore significance himself, but also that the continuation of his line and therefore name really depends largely, so as not to say entirely – although very likely that too – on him, which would make him a firstborn or only son.

And while we don't know very much at all about the relationship, such as it is, between the young man and the poet yet, we get a sense from the tone of Sonnet 4 that we are in something of a transactional setting; an impression that is somewhat supported by the absence of any real emotion or personal investment in these first few poems: I the poet, William Shakespeare, do call the young man a number of paradoxical things, such as a "beauteous niggard," or an "unthrifty loveliness," but these are fairly generic terms that any poet could write about any person of whom one or two basic things are known, in this instance namely that they are beautiful and that they are not purposeful enough in the pursuit of the perpetuation of their lineage.

In other words, apart from the few things we now know about Shakespeare and the young man from just these sonnets, we also know that there are quite a few things we actually genuinely don't know. And this, though it may not at first glance seem so, is itself tremendously exciting and very useful indeed, because once you know what you don't know, you may know what to look for in the things you do know...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!