Sonnet 26: Lord of My Love, to Whom in Vassalage

|

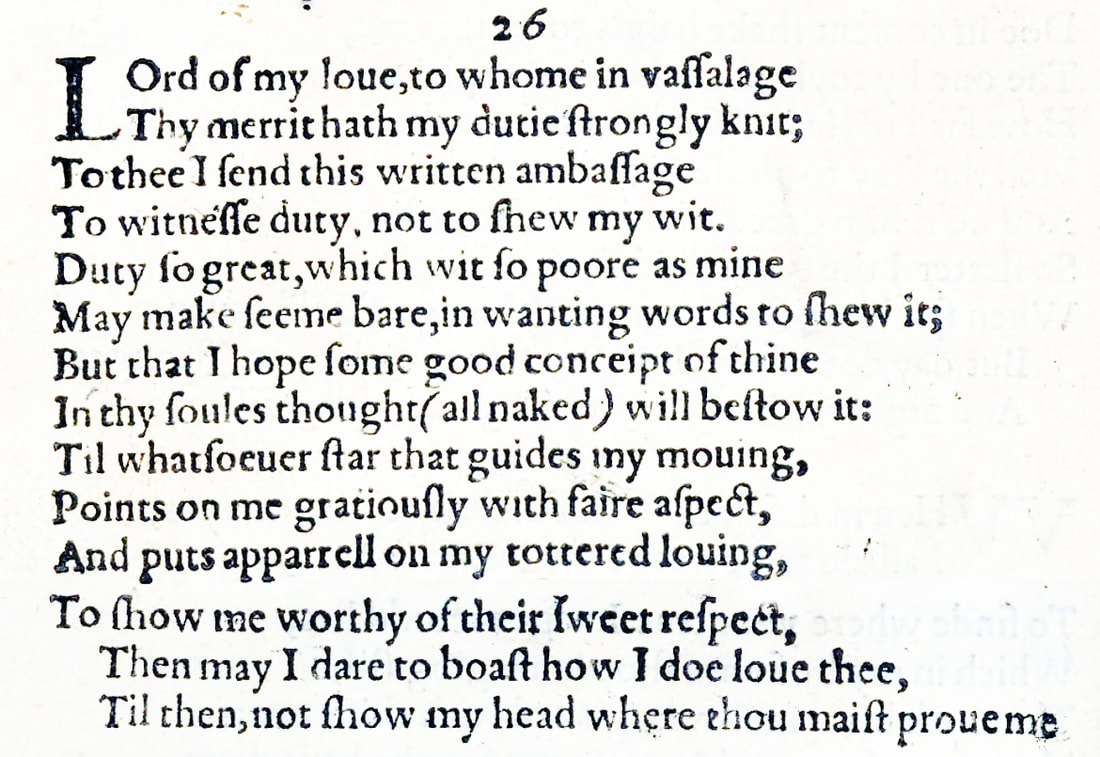

Lord of my love, to whom in vassalage

Thy merit hath my duty strongly knit, To thee I send this written ambassage, To witness duty, not to show my wit. Duty so great, which wit so poor as mine May make seem bare, in wanting words to show it, But that I hope some good conceit of thine, In thy soul's thought, all naked, will bestow it, Till whatsoever star that guides my moving Points on me graciously, with fair aspect, And puts apparel on my tattered loving To show me worthy of thy sweet respect. Then may I dare to boast how I do love thee, Till then not show my head where thou mayst prove me. |

|

Lord of my love, to whom in vassalage

Thy merit hath my duty strongly knit, |

Lord of my love, to whom on account of your status and your great worth as a person – your merit – I am obliged in a bond of loyalty and service...

A vassal in mediaeval Europe was a knight who swore loyalty to a king or a lord, often offering military service and allegiance, in return for protection and special privileges and rewards, for example the possession of land. While it therefore does have a meaning of servitude and subordination, this is not necessarily understood to be a bad thing: the relationship between a vassal and his suzerain – as the other party is then called – was often mutually beneficial, and since the status of a king or a queen was generally accepted as God-given and immutable, being able to enter such an arrangement would absolutely be seen as a privilege quite as much as a duty. |

|

To thee I send this written ambassage,

To witness duty, not to show my wit. |

...to you do I send this written message, the purpose of which is to show and acknowledge my duty, not to show off how brilliant I am, or, more specifically, since I am a poet and this is a poem, how good my writing is.

An 'ambassage', which today we would call an embassage, is a message that would ordinarily be relayed by an envoy or indeed an ambassador, and usually suggests a verbal communication that is conveyed by the person carrying it, rather than a letter that is simply sent. The fact that the embassage here is a written one is therefore of pointed significance: the sender and the recipient are apart and the intermediary – the emissary, so to speak – is this poem itself, which therefore metaphorically then 'stands' before the recipient. |

|

Duty so great, which wit so poor as mine

May make seem bare, in wanting words to show it, |

A duty that is so great that a writing skill as poor as mine may appear bare or naked, and thus wholly inadequate, incapable of expressing how important I consider my duty to be and how highly I therefore esteem you.

'Wit' here as elsewhere – and as we saw very recently in Sonnet 23 – is a knowledge or skill or ability quite generally, but by implication in this context a skill related to the poetry itself. It does not necessarily imply what we today would refer to as 'wittiness'. |

|

But that I hope some good conceit of thine,

In thy soul's thought, all naked, will bestow it |

But I hope that you will find it in your heart – your soul's thought – to give it the benefit of our generous consideration and, although this poor skill of mine stands before you naked and inadequate, that you may 'bestow' it with the imaginary clothing of your kindness, treating it as if it were better than it is...

|

|

Till whatsoever star that guides my moving

Points on me graciously, with fair aspect |

Until whatever star that may influence my actions and determine my life looks on me favourably and creates auspicious circumstances...

This of course references straight back to Sonnet 25, where William Shakespeare talked of "those who are in favour with their stars," referring to people who were luckier than he. The idea that the stars have a direct impact on our lives was then as now not only held by many people to be literally true, but also of proverbial use to express the notion of luck or fortune generally, much as we today speak of thanking our 'lucky stars', whether or not we actually believe in horoscopes. |

|

And puts apparel on my tattered loving

To show me worthy of thy sweet respect. |

...and clothes my bare and therefore poor and unworthy expressions of love with a greater skill and better words, so that I can appear before you in a state that is worthy of your respect.

In Sonnet 2 we had the 'tattered weed' to describe the once 'proud livery' of the young nobleman's youth when he is forty. In a society where status was of greatest importance and where this status was by necessity expressed through clothing, having your appearance in tatters very much suggested that your life was equally ruined. The idea, therefore, that in order to gain the respect of other people you need to present yourself respectably was infinitely stronger then than it is now: you would not dare to appear before a king or a queen or a lord or a lady in 'causal wear', not least because the concept did not even exist at the time. |

|

Then may I dare to boast how I do love thee,

Till then not show my head where thou mayst prove me. |

Then, when that is the case, when fortune has given me the wherewithal to express myself with words that dress my love in a way that makes me appear deserving, only then shall I be allowed to boast of my love for you. Until then, I may not show my face in any place where you are and would therefore be able to put me to the test.

'Boast' also references the previous Sonnet 25 directly: there it was the people who are "in favour with their stars" who boast of their "public honour and proud titles." The fact that Shakespeare uses the word here when talking of how he loves the young man strongly suggests that, much as in that other context, the word implies a palpable lack of modesty on behalf of the speaker, here Shakespeare himself. |

The obsequious, so as not to say startlingly submissive, Sonnet 26 radically changes the tone and therefore our perception of the constellation between William Shakespeare and the young man: gone is the confidence of Sonnet 25, gone, even, is the complexity of Sonnet 24 and the uncertainty of Sonnet 23, long gone seems the joy and exuberance of Sonnet 18. With Sonnet 26, William Shakespeare effectively withdraws, resets, and almost apologises for having been presumptuous in his declarations of love.

We continue to only be able to speculate about what exactly happens between our poet and his young lover in-between sonnets, but if ever we needed an indication that maybe things are moving way too fast for the young man, that he is really on quite a different plane than his admirer – who is, after all, at least ten years his senior at a time when ten years make a big difference in a young man's life – then it is this sonnet.

Whatever the young man has said or done, whichever way he responded to what has gone before, William Shakespeare with this sonnet concedes that he may have spoken – as in written – out of turn. Of course, with this sonnet as with many others before, there is always the possibility that absolutely nothing happened, that Shakespeare is just going through the motions of what-ifs and how-abouts and other hypothetical scenarios. But we have no good reason to believe that this is so. Just look at the sequence of what these sonnets in essence are saying:

22: My heart lives in your breast as yours in mine: we are as one. Do not expect your heart back, because you gave it to me for it not to be given back again: you have effectively committed yourself to me.

23: I don't always know the right things to say when we see each other, but read my poetry to understand how much you mean to me. Please don't expect me to shower you with compliments when we're together, I can express myself much better in my poems.

24: I have taken you into my heart and I adore you; but the truth is, I cannot be sure that you feel the same about me.

25: Yeay! You feel the same about me. We are together after all. And that must never change: I cannot leave you and I cannot now be sent away from you, which means you cannot and you will not leave me.

26: Oh dear. I'm sorry if that sounded like I am making assumptions about our relationship and our future. I realise you have said no such thing and obviously I can't tell you what you may or may not do: that would be ridiculous. All you have said is that you love me too, but yes, you may be in a completely different place in your life, and in any case your life belongs to you.

If William Shakespeare and this young man had had Facebook at the time, Will's relationship status would just have had to be set to: "it's complicated." And it is going to get a whole lot more complicated fairly soon...

How, though, do we know that Sonnet 26 really follows Sonnet 25, and 25 the ones that went before? We don't. But here too, we have no good reason to believe that they don't follow each other in more or less exactly this order. Certainly, Sonnet 26 makes a point of saying:

Then may I dare to boast how I do love thee

Till then not show my head where thou mayst prove me.

When in Sonnet 25 I, the poet, William Shakespeare, had started by declaring:

Let those who are in favour with their stars

Of public honour and proud titles boast

There rather implying that boasting is an uncouth, inappropriate thing to do and contrasting such boastfulness with my own humble devotion to you:

Whilst I, whom fortune of such triumph bars

Unlooked for joy in that I honour most.

Is the fact that I use the word 'boast' now in Sonnet 26 to describe what I may only do once I have been given better, less 'tattered' words to talk about my love for you a coincidence? Hardly. Yes, it could be, but it is much more likely that William Shakespeare here actively and consciously backtracks, holds his hands up and says: sorry. I went too far too fast.

What we also learn from Sonnet 26 are two more things. Firstly, we have so far largely been inferring from the previous sonnets and the words they contain that the young man in question is an English nobleman of high social status. There is – within those words –plenty of evidence that points towards this and in many instances we have found that the words that Shakespeare chooses could only realistically be addressed to someone of that ilk. Sonnet 26 – probably without specifically meaning to do so for our benefit, but largely to appease its apparently disaffected recipient – spells out this dynamic of power in much more explicit terms. Yes, these too could – in theory – be just be here being used for poetic effect, but why should we assume such a thing when the other possibility, that they describe an actual real-life constellation offers itself so readily, and so obviously? Does it bear saying once again so soon already: in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. And this here seems a great deal more likely:

Lord of my love, to whom in vassalage

Thy merit hath my duty strongly knit

Of course you can call your stableboy lover 'lord of my love' in a poem. But we know for certain that at least one of the principal candidates for the young man – Henry Wriothesley, the third Earl of Southampton – had two long narrative poems dedicated to him by Shakespeare, and one posthumous source claims that Southampton on one occasion gave Shakespeare £1,000, which would have been roughly £120,000 or about €135,000 or $143,000 in today's money. It is disputed whether or not this is true, and we will dedicate an entire episode to the young man and who the most likely candidates are for him, but what we can certainly entertain is the possibility that the relationship between William Shakespeare and his young lover goes beyond that of a romantic association and the perfectly obvious infatuation. That quite conceivably William Shakespeare is either already receiving, or is seeking, the patronage of his young lover. And that would be far from unusual: poets at the time needed patrons. And these patrons were often excessively rich. All of which, I have to say, is at this point pure speculation. What the words themselves tell us here is simply this: as far as I, William Shakespeare, am concerned, your merit – be this one in my imagination or one underpinned by your status in society – ties my duty to you in 'vassalage': a bond of loyalty.

And here the choice of the word 'vassalage' may well also be significant: a vassalage is a sworn allegiance to a person of superior status, such as a lord, a king, or a queen, but it comes in return for certain specified privileges or benefits. 'Fealty', by contrast, is an unconditional oath of loyalty. Shakespeare would have had the wherewithal to compose a poem that rhymes and scans around 'fealty' or indeed any other word of his choice. The fact that he uses 'vassalage' may well have its reasons. And seeing how the rest of the poem concerns itself not, in actual fact, with emotions so much as with the expressions of love, meaning words, meaning writing, it is entirely possible, though no more than that, and certainly not certain, that Shakespeare here has this additional layer of their already current or as far as he himself is concerned intended relationship in mind.

Secondly, and this may almost sound mundane in its simplicity by comparison, Shakespeare is away from the young man. Or nearly. What we actually know and what the words themselves clearly und indisputably tell us is that this sonnet is being sent to the young man as a written message: "To thee I send this written ambassage." There is – in theory again – a possibility that Shakespeare writes this written embassage and then takes it to the young man himself and reads it to him, but that is plainly absurd. Much more likely is either that Shakespeare, while still in London, sends the message because he doesn't want to show his face to the young man – and he has after all already explained that he is better at writing than at speaking, so it is entirely plausible that Shakespeare could go and see the young man, but chooses not to – or either he or the young man, is out of town.

And the sonnet that will give us a great deal of clarity indeed about this particular question is the one that follows next: Sonnet 27...

We continue to only be able to speculate about what exactly happens between our poet and his young lover in-between sonnets, but if ever we needed an indication that maybe things are moving way too fast for the young man, that he is really on quite a different plane than his admirer – who is, after all, at least ten years his senior at a time when ten years make a big difference in a young man's life – then it is this sonnet.

Whatever the young man has said or done, whichever way he responded to what has gone before, William Shakespeare with this sonnet concedes that he may have spoken – as in written – out of turn. Of course, with this sonnet as with many others before, there is always the possibility that absolutely nothing happened, that Shakespeare is just going through the motions of what-ifs and how-abouts and other hypothetical scenarios. But we have no good reason to believe that this is so. Just look at the sequence of what these sonnets in essence are saying:

22: My heart lives in your breast as yours in mine: we are as one. Do not expect your heart back, because you gave it to me for it not to be given back again: you have effectively committed yourself to me.

23: I don't always know the right things to say when we see each other, but read my poetry to understand how much you mean to me. Please don't expect me to shower you with compliments when we're together, I can express myself much better in my poems.

24: I have taken you into my heart and I adore you; but the truth is, I cannot be sure that you feel the same about me.

25: Yeay! You feel the same about me. We are together after all. And that must never change: I cannot leave you and I cannot now be sent away from you, which means you cannot and you will not leave me.

26: Oh dear. I'm sorry if that sounded like I am making assumptions about our relationship and our future. I realise you have said no such thing and obviously I can't tell you what you may or may not do: that would be ridiculous. All you have said is that you love me too, but yes, you may be in a completely different place in your life, and in any case your life belongs to you.

If William Shakespeare and this young man had had Facebook at the time, Will's relationship status would just have had to be set to: "it's complicated." And it is going to get a whole lot more complicated fairly soon...

How, though, do we know that Sonnet 26 really follows Sonnet 25, and 25 the ones that went before? We don't. But here too, we have no good reason to believe that they don't follow each other in more or less exactly this order. Certainly, Sonnet 26 makes a point of saying:

Then may I dare to boast how I do love thee

Till then not show my head where thou mayst prove me.

When in Sonnet 25 I, the poet, William Shakespeare, had started by declaring:

Let those who are in favour with their stars

Of public honour and proud titles boast

There rather implying that boasting is an uncouth, inappropriate thing to do and contrasting such boastfulness with my own humble devotion to you:

Whilst I, whom fortune of such triumph bars

Unlooked for joy in that I honour most.

Is the fact that I use the word 'boast' now in Sonnet 26 to describe what I may only do once I have been given better, less 'tattered' words to talk about my love for you a coincidence? Hardly. Yes, it could be, but it is much more likely that William Shakespeare here actively and consciously backtracks, holds his hands up and says: sorry. I went too far too fast.

What we also learn from Sonnet 26 are two more things. Firstly, we have so far largely been inferring from the previous sonnets and the words they contain that the young man in question is an English nobleman of high social status. There is – within those words –plenty of evidence that points towards this and in many instances we have found that the words that Shakespeare chooses could only realistically be addressed to someone of that ilk. Sonnet 26 – probably without specifically meaning to do so for our benefit, but largely to appease its apparently disaffected recipient – spells out this dynamic of power in much more explicit terms. Yes, these too could – in theory – be just be here being used for poetic effect, but why should we assume such a thing when the other possibility, that they describe an actual real-life constellation offers itself so readily, and so obviously? Does it bear saying once again so soon already: in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. And this here seems a great deal more likely:

Lord of my love, to whom in vassalage

Thy merit hath my duty strongly knit

Of course you can call your stableboy lover 'lord of my love' in a poem. But we know for certain that at least one of the principal candidates for the young man – Henry Wriothesley, the third Earl of Southampton – had two long narrative poems dedicated to him by Shakespeare, and one posthumous source claims that Southampton on one occasion gave Shakespeare £1,000, which would have been roughly £120,000 or about €135,000 or $143,000 in today's money. It is disputed whether or not this is true, and we will dedicate an entire episode to the young man and who the most likely candidates are for him, but what we can certainly entertain is the possibility that the relationship between William Shakespeare and his young lover goes beyond that of a romantic association and the perfectly obvious infatuation. That quite conceivably William Shakespeare is either already receiving, or is seeking, the patronage of his young lover. And that would be far from unusual: poets at the time needed patrons. And these patrons were often excessively rich. All of which, I have to say, is at this point pure speculation. What the words themselves tell us here is simply this: as far as I, William Shakespeare, am concerned, your merit – be this one in my imagination or one underpinned by your status in society – ties my duty to you in 'vassalage': a bond of loyalty.

And here the choice of the word 'vassalage' may well also be significant: a vassalage is a sworn allegiance to a person of superior status, such as a lord, a king, or a queen, but it comes in return for certain specified privileges or benefits. 'Fealty', by contrast, is an unconditional oath of loyalty. Shakespeare would have had the wherewithal to compose a poem that rhymes and scans around 'fealty' or indeed any other word of his choice. The fact that he uses 'vassalage' may well have its reasons. And seeing how the rest of the poem concerns itself not, in actual fact, with emotions so much as with the expressions of love, meaning words, meaning writing, it is entirely possible, though no more than that, and certainly not certain, that Shakespeare here has this additional layer of their already current or as far as he himself is concerned intended relationship in mind.

Secondly, and this may almost sound mundane in its simplicity by comparison, Shakespeare is away from the young man. Or nearly. What we actually know and what the words themselves clearly und indisputably tell us is that this sonnet is being sent to the young man as a written message: "To thee I send this written ambassage." There is – in theory again – a possibility that Shakespeare writes this written embassage and then takes it to the young man himself and reads it to him, but that is plainly absurd. Much more likely is either that Shakespeare, while still in London, sends the message because he doesn't want to show his face to the young man – and he has after all already explained that he is better at writing than at speaking, so it is entirely plausible that Shakespeare could go and see the young man, but chooses not to – or either he or the young man, is out of town.

And the sonnet that will give us a great deal of clarity indeed about this particular question is the one that follows next: Sonnet 27...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!