Sonnet 30: When to the Sessions of Sweet Silent Thought

|

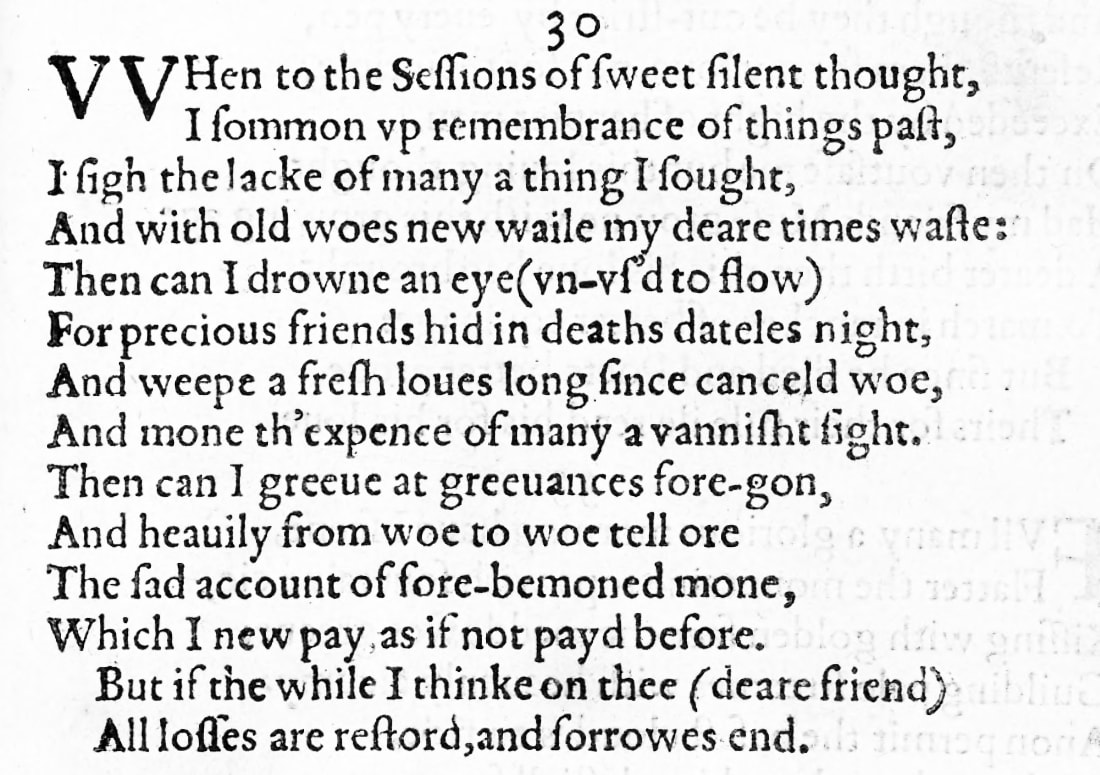

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past, I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought, And with old woes new wail my dear time's waste. Then can I drown an eye, unused to flow, For precious friends hid in death's dateless night, And weep afresh love's long since cancelled woe, And moan th'expense of many a vanished sight. Then can I grieve at grievances foregone And heavily from woe to woe tell ore The sad account of fore-bemoaned moan, Which I new pay, as if not paid before. But if the while I think on thee, dear friend, All losses are restored, and sorrows end. |

|

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past |

When I ponder my life and remember things that have happened in the past...

Most editors point out that 'sessions' and 'summon' are legal terms, whereby 'sessions' refers to court sessions, and 'summon' to the calling of witnesses. Shakespeare often uses references from the worlds of law and finance in his poems and this here is no doubt the case and deliberate. Perhaps noteworthy too though is that William Shakespeare speaks of theses as sessions 'of sweet silent thought' which really rather characterises them in quite a particular, and not entirely negative, nor overly formal, way and thus from the outset distinguishes this poem from the previous one which at first glance appears very similar in its content and which it is – also without doubt – connected to. By calling them 'the sessions', he implies that they are a regular feature, if not of life generally, then certainly of his life, which is unsurprising, considering Shakespeare's particular lifestyle, which in turn is characterised by long extended absence from his family at home in Stratford and by sporadic but painful separations from his young lover in London. And by describing them as sessions of 'sweet silent thought', he also implies that there is something lovely, pleasurable, perhaps even indulgent about these moments of solitude and reflection: maybe a melancholy nostalgia that is not entirely unpleasant. Absent here, certainly, seems the despair and dejection of the previous sonnets, signalling a much more purely reflective mode. |

|

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought

|

...I regret or feel sorry about the fact that many things I sought or wished to achieve have not materialised...

We would expect an 'about' here after 'sigh' to make the line clear: 'I sigh about the lack...' This would appear to support the impression we received in Sonnet 29 that Shakespeare is unhappy with his career trajectory to date. |

|

And with old woes new wail my dear time's waste.

|

And with these old woes – things I have dreamt of achieving that I haven't achieved, things I have always wanted and didn't get – I yet again newly complain or even cry about how I have wasted my precious time.

Time, we have noted before, is of immense importance to Shakespeare and this is only one of many indications we receive throughout these sonnets that he feels his time is running out, even though he can't be anywhere near as old by this time as we might be led to believe. |

|

Then can I drown an eye, unused to flow,

|

Then, when I am thinking about these things, can it happen that I well up with tears even though I am not used to crying...

The fact that William Shakespeare describes his eye as 'unused to flow', meaning that it is not in the habit of producing tears, suggests that he usually takes quite a stoic, so as not to say hardened or world-weary view of things and is not that easily moved to tears. |

|

For precious friends hid in death's dateless night,

|

...for precious friends of mine who have since passed away and are therefore now hidden in the endless night of death.

'Friends' here as elsewhere is possibly ambiguous. Shakespeare later on in this particular sonnet and on many other occasions refers to the young man who is clearly a lover, as his 'friend' and so whether he here at this point means 'just' good friends or former lovers is not clear. Certainly, mortality in London in Shakespeare's day is such that even among his own and the young man's generation there may easily have been several friends of any description who have since died. In Sonnet 14 Shakespeare said to the young man that unless he was to produce a son, his end would be both truth's and beauty's "doom and date." Here, similarly, 'date' is used to mean 'final date' and therefore 'termination' or 'end', except of course that death and with it the night of death has no final date, it lasts forever and is therefore 'dateless'. As a marginal perhaps: Shakespeare does not always and everywhere think of death as 'dateless'. The Christian tradition, in which he grew up, envisages a Judgment Day when the dead arise and in Sonnet 58, for example, he will refer to this directly, saying to the young man: So, till the judgment that yourself arise, You live in this and dwell in lovers' eyes. But this clearly has no bearing on the meaning and sentiment of this sonnet here. |

|

And weep afresh love's long since cancelled woe,

|

Then, when I am thinking of the past, I can weep again with fresh tears about a love that has long since ended and whose sorrows are therefore long since cancelled and expired; in other words, I can bring up all those feelings of loss and sorrow all over again, even though I have long since convinced myself that I have moved on...

|

|

And moan th'expense of many a vanished sight.

|

...and at the same time and in the same way I can bemoan the metaphorical expense – meaning mostly the emotional effort that has gone into – many a 'sight' that has since disappeared.

What exactly is meant here by 'sight' is not clear or specified, but in the context of 'love's long since cancelled woe' above, what springs to mind is certainly the sight of a beautiful person whom I may have fancied or pursued. This is the first but not the only time that Shakespeare suggests he has had lovers before and other than the young man. The clearest and most explicit reference to them is yet to come in Sonnet 31. |

|

Then can I grieve at grievances foregone

|

Then – always and still at that time of reflection, of course – can I newly grieve at the grievances which are foregone because they lie in the past, in other words I can again wallow to some extent in the pain of being an injured party, be that now in love or in any other matter...

|

|

And heavily from woe to woe tell ore

The sad account of fore-bemoaned moan |

...and once again with a heavy heart give myself – or anybody who might be nearby to hear it – a blow by blow account of the things I have moaned about possibly many times before...

And while 'woe to woe' does have the meaning here, more or less, of a 'blow by blow' account, it is almost endearing how Shakespeare here seems to almost mock himself by the repetition of the gravely laden word woe. |

|

Which I new pay, as if not paid before.

|

And this account that I give, of the sad wrongs I have suffered, I pay it off all over again, as if I had not done so before.

This is a particularly clever word play: an account is obviously a telling or here quite specifically a retelling of a story, but it is also a reckoning or a bill. Shakespeare here first treats it as the former, and then switches the meaning to the latter, by suggesting he newly pays this bill, as if he hadn't done so before. The 'payment' of course is a metaphorical one, again in emotion, in pain, in regret, in loss, rather than a financial one executed in money. By once again going through these emotions, he is once again 'paying' this 'account', as if he hadn't done so many times before. |

|

But if the while I think on thee, dear friend,

All losses are restored, and sorrows end. |

But – and in a direct echo of Sonnet 29 – here too it is true: if while I am so engaged in my self-pitying reminiscences, I think of you, my dear friend, then in an instant all these losses that I have suffered are as good as restored and all my sorrows cease immediately, because – by implication and as we already know from the previous sonnet – you make me so rich and so happy that nothing else matters any more.

Colin Burrows in the Oxford Shakespeare edition highlights the fact that this is the first sonnet in which William Shakespeare addresses his young lover as 'dear friend', and the use of 'friend' to mean a person whom the writer is engaged in a romantic relationship with is certainly well established in poetry at the time. |

Sonnet 30 picks up on the theme of Sonnet 29 and develops the 'sweet love' remembered there into a reminiscence about lost love, missed opportunity and failed aspirations, among which again it is the thought of the young man that has the power, here not so much to simply lift the spirit and therefore the state of mind and heart, but to restore the losses suffered and to end the sorrows they have brought – to, in essence, heal.

It is this a calmer, more pensive sonnet than the one it so follows, and it feels almost as if I, the poet, William Shakespeare, am here taking a step back to listen to myself and ponder the things I've just said, sensing a wry smile tease my lips as I recount now how I, in these moments of thoughtfulness and wistful remembrance recount my woes. There is an understated playfulness at work, with my word play on legalese that is only just introduced and then not further pursued, with the sensory pleasure I take in several resonant alliterations, with the repetitions and rueful enumerations.

I, your podcaster, Sebastian Michael, not all that long ago wrote William Shakespeare as a character into a playlet that features as part of a short novel called Orlando in the Cities, where in conversation with Ben Jonson, I made him say about London: "It is a place for irony. Which I am useless at. A constant knowing contradiction within everything." But here we get the impression that Shakespeare is perhaps being a little ironic, that he is looking at himself through the prism of a more objective bystander and poking gentle fun at himself. Either that, or he is being disarmingly honest in his assessment of his own tendency to self-indulge when left to his own devices.

Sonnet 30 is one of my favourite sonnets because it is both multi-layered and simple, artfully crafted and wonderfully direct, and like so many others, only perhaps even more so, it is utterly relatable. You do not have to be an under-appreciated poet of the 16th century to know exactly what Will is talking about: he here comes across very much as the friend who is just like us, or, if I continue to speak for myself, just like me: looking back, in a moment of 'sweet silent thought', do I breathe a deep sigh over things I wish I had achieved or done by now and simply didn't or couldn't or failed at? Absolutely. Do I look at how fast time has passed and how much of it seems to have been wasted, by none other than me? Indeed I do. Can I, who hardly ever cry for or about anything, dissolve in a heap of tears about precious friends who are no longer with us and whose passing I still can never properly comprehend? My eyes well up as I ask the question. Do I need to go through the entire sonnet and confirm each parallel to my own frame of experience? Probably not: you get the gist.

Sonnet 30 does not ask many questions, nor does it really answer any. And that may be exactly what makes it so precious as a piece of poetry. It clearly and obviously appears as part of the sequence, it stands on its own, though it relates obviously to the one before and also the one that comes after and – intelligent and craftily composed as it is – it seems to come straight from the heart. It is a wonder of poetic writing, because it is so profoundly personal and yet so universal that a man born four hundred years later like myself could still put my signature to it and say: that's exactly how I feel on occasion.

The single textual detail that may yield up something close to a new or potentially significant insight comes with the closing couplet, and it is possibly telling – possibly just a coincidence – that in the Quarto Edition it is set in brackets: "dear friend". It is, as we noted above, the first time in the series that I, William Shakespeare, address the young man as 'dear friend', and it lends the sonnet a particularly authentic and intimate quality. There is no doubt that by now I nurture a great love for this young man and genuinely hold him dear, and it is also clear that no matter how much I love him, he will always 'only' be my friend: there is no other, higher, level of affection or deeper sense of connection that is available in the culture of the day, and so whether or not our relationship is already now, or is yet to become, or may never be physically intimate, the absolutely best I can have is you as my dear friend. It is more and better than any 'lover' or 'love' or affair or mistress or probably, in the sense of this immense sense of adoration, even 'wife'.

No, this poem does not make any pronouncements about any of these, and they all exist, it does not qualify my love for my lovers and loves, my lust for my mistress or anyone else, or my commitment to my wife, but it does mark the young recipient of these fourteen lines out as my 'dear friend', and very soon I will have reason and need to get incredibly angry with him, to forgive him, and to tell the world that 'my friend and I are one', and so: in brackets it may originally have been set, a throwaway form of address to us it may seem, but meaningless it is certainly not.

The fact that the young man is here now at this point directly called William Shakespeare's dear friend establishes the bond between them as affirmed, as declared and as real. And it is only really because the relationship has evolved to this stage that it can withstand what is very soon to test it almost – but fortunately for us, and for Will, and for the young man, not quite – to breaking point and beyond...

It is this a calmer, more pensive sonnet than the one it so follows, and it feels almost as if I, the poet, William Shakespeare, am here taking a step back to listen to myself and ponder the things I've just said, sensing a wry smile tease my lips as I recount now how I, in these moments of thoughtfulness and wistful remembrance recount my woes. There is an understated playfulness at work, with my word play on legalese that is only just introduced and then not further pursued, with the sensory pleasure I take in several resonant alliterations, with the repetitions and rueful enumerations.

I, your podcaster, Sebastian Michael, not all that long ago wrote William Shakespeare as a character into a playlet that features as part of a short novel called Orlando in the Cities, where in conversation with Ben Jonson, I made him say about London: "It is a place for irony. Which I am useless at. A constant knowing contradiction within everything." But here we get the impression that Shakespeare is perhaps being a little ironic, that he is looking at himself through the prism of a more objective bystander and poking gentle fun at himself. Either that, or he is being disarmingly honest in his assessment of his own tendency to self-indulge when left to his own devices.

Sonnet 30 is one of my favourite sonnets because it is both multi-layered and simple, artfully crafted and wonderfully direct, and like so many others, only perhaps even more so, it is utterly relatable. You do not have to be an under-appreciated poet of the 16th century to know exactly what Will is talking about: he here comes across very much as the friend who is just like us, or, if I continue to speak for myself, just like me: looking back, in a moment of 'sweet silent thought', do I breathe a deep sigh over things I wish I had achieved or done by now and simply didn't or couldn't or failed at? Absolutely. Do I look at how fast time has passed and how much of it seems to have been wasted, by none other than me? Indeed I do. Can I, who hardly ever cry for or about anything, dissolve in a heap of tears about precious friends who are no longer with us and whose passing I still can never properly comprehend? My eyes well up as I ask the question. Do I need to go through the entire sonnet and confirm each parallel to my own frame of experience? Probably not: you get the gist.

Sonnet 30 does not ask many questions, nor does it really answer any. And that may be exactly what makes it so precious as a piece of poetry. It clearly and obviously appears as part of the sequence, it stands on its own, though it relates obviously to the one before and also the one that comes after and – intelligent and craftily composed as it is – it seems to come straight from the heart. It is a wonder of poetic writing, because it is so profoundly personal and yet so universal that a man born four hundred years later like myself could still put my signature to it and say: that's exactly how I feel on occasion.

The single textual detail that may yield up something close to a new or potentially significant insight comes with the closing couplet, and it is possibly telling – possibly just a coincidence – that in the Quarto Edition it is set in brackets: "dear friend". It is, as we noted above, the first time in the series that I, William Shakespeare, address the young man as 'dear friend', and it lends the sonnet a particularly authentic and intimate quality. There is no doubt that by now I nurture a great love for this young man and genuinely hold him dear, and it is also clear that no matter how much I love him, he will always 'only' be my friend: there is no other, higher, level of affection or deeper sense of connection that is available in the culture of the day, and so whether or not our relationship is already now, or is yet to become, or may never be physically intimate, the absolutely best I can have is you as my dear friend. It is more and better than any 'lover' or 'love' or affair or mistress or probably, in the sense of this immense sense of adoration, even 'wife'.

No, this poem does not make any pronouncements about any of these, and they all exist, it does not qualify my love for my lovers and loves, my lust for my mistress or anyone else, or my commitment to my wife, but it does mark the young recipient of these fourteen lines out as my 'dear friend', and very soon I will have reason and need to get incredibly angry with him, to forgive him, and to tell the world that 'my friend and I are one', and so: in brackets it may originally have been set, a throwaway form of address to us it may seem, but meaningless it is certainly not.

The fact that the young man is here now at this point directly called William Shakespeare's dear friend establishes the bond between them as affirmed, as declared and as real. And it is only really because the relationship has evolved to this stage that it can withstand what is very soon to test it almost – but fortunately for us, and for Will, and for the young man, not quite – to breaking point and beyond...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!