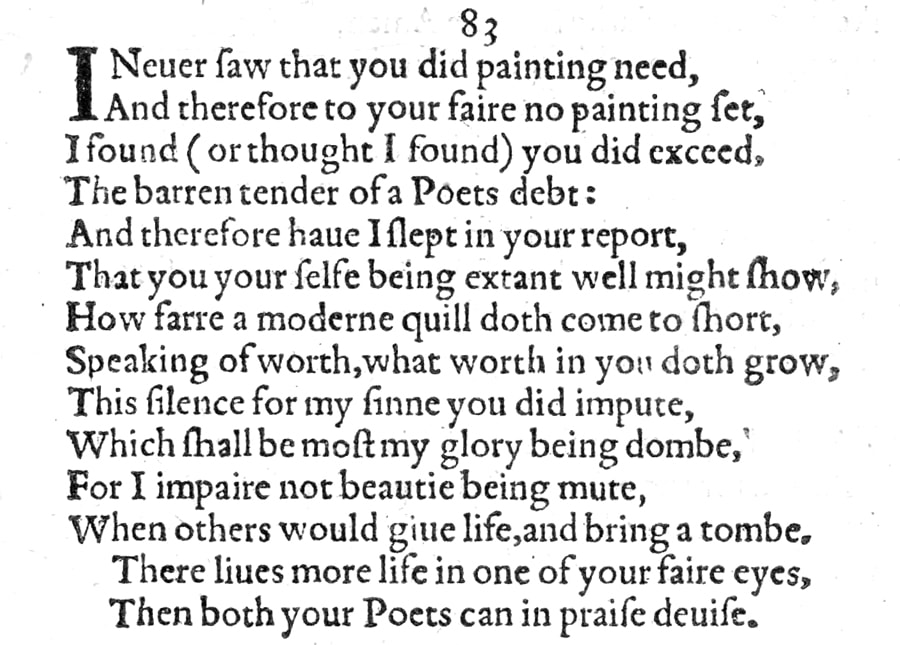

Sonnet 83: I Never Saw That You Did Painting Need

|

I never saw that you did painting need,

And therefore to your fair no painting set. I found, or thought I found, you did exceed The barren tender of a poet's debt. And therefore have I slept in your report, That you yourself, being extant, well might show How far a modern quill doth come too short, Speaking of worth, what worth in you doth grow. This silence for my sin you did impute, Which shall be most my glory, being dumb, For I impair not beauty, being mute, When others would give life and bring a tomb. There lives more life in one of your fair eyes Than both your poets can in praise devise. |

|

I never saw that you did painting need,

|

The sonnet, while it can also stand on its own, picks up on the argument laid out by Sonnet 82 which ended on the idea that the 'gross painting' in words – meaning the exaggerated, even crass representation of the young man in their poetry – by other poets would be better applied to those who need this kind of insincere flattery. "In thee," Shakespeare there told the young man "it is abused." Here, he elaborates and gives his reasons why this is so.

I never saw or, as we might also say, felt that you needed to be thus painted in words. We might think of this as a 'description' of the young man, and indeed, as we noted in our last episode, Shakespeare never once actually properly describes the young man beyond giving us some very basic characteristics and features, such as the immensely telling and frank observations in Sonnet 20: A woman's face, with nature's own hand painted Hast thou, the, master-mistress of my passion. And it is significant that in that instance, the 'painting' referred to is done by nature itself, not by an artist – as in a painted portrait – and not by any artifice, there specifically make-up. Much as the artificial 'painting' of a face with make-up is not something Shakespeare can approve of, he also disdains hyperbolic 'painting' in words, which is why in relation to the young man he eschews it, since the young man clearly doesn't need it, being as naturally beautiful as he is. |

|

And therefore to your fair no painting set.

|

And so because of this I have never made such a 'painting' in words to your beauty in all my poetry, and as I told you and the world just recently, in Sonnet 76, I have written many, many poems by now which always are for, about, and to you. In all of this large body of sonnets, still growing, I have never once described you or tried to make you sound more beautiful than you are, because that in itself would be, as is implied here and as I am about to spell out, in any case impossible.

|

|

I found, or thought I found, you did exceed

The barren tender of a poet's debt. |

I saw and found – as in realised or came to the conclusion – that you, in your beauty and your worth generally, exceeded the poor, inadequate offerings of a poet who is indebted to you.

Striking is the qualification with "or thought I found," which, in an unusually self-conscious twist, relativises Shakespeare's own assessment of the situation. Shakespeare seems to be saying to his young lover: you don't need me to paint you in flowery poetry, or so I thought... – leaving us to wonder what exactly the desired effect is of this, or why he says it. An answer to this will come a little later in the poem, where Shakespeare infuses a note of disapproval, maybe even disappointment with the young man for even expecting to be 'painted', something that will find an even stronger expression in the closing couplet of Sonnet 85. And by suggesting that such 'painting in words' as a poet might have to offer comes as a tender of his debt, Shakespeare again – as he has done several times now in this group of sonnets – alludes to such a poet, possibly just like himself, being in the young man's debt; that he therefore owes him poetry, either in return for actual moneyed patronage, or in return for his endorsement, his support, his friendship, his association with him. It is this one of many, many indications throughout the canon of these sonnets that the young man is a person of high social standing. |

|

And therefore have I slept in your report

|

And because of this I have remained quiet about your beauty...

Much here is implied: "have I slept" suggests a subtle level of admission of guilt and self-admonishment, as in 'I have slept through this', or 'I have been asleep'. It evokes a more passive kind of omission that comes with a lack of awareness: 'I have not been fully awake and alert to your needs'. And "in your report" is a very condensed and also layered way of saying 'in my writing about you', because it contains on the one hand the element of my reporting on you, meaning announcing, or as we might say today broadcasting, to the world how entirely wonderful and gorgeous you are, but it also, on the other hand, references a reputation, which then takes into consideration again what other people are doing and saying: I have been asleep to this chorus of approval that you are getting from others and not even tried to keep up with it. And with this, the passive note of failure on the part of the poet is now turned on its head with an active intention: |

|

That you yourself being extant well might show

How far a modern quill doth come too short, Speaking of worth, what worth in you doth grow. |

And I did this, I remained quiet about your beauty, so that you yourself, who you are alive and therefore exist as a real person in this world, might show to the world just how far the writing of a modern poet comes short when it speaks of worth generally, and very specifically of your worth. 'Worth' always meaning your overall marvellousness.

The quill is simply the pen and here stands for both the person using it, the poet, and their output, the poetry: writers in Elizabethan England used bird feathers to write – a technique that has long since vanished from common practice but that I in fact still learnt at school, not because we needed it but because our curriculum wanted us to experience what writing with quill and ink feels like. And I can tell you it works, but it makes for a scratchy script, that is prone to blots and strokes of irregular thickness, and takes some time to acquire as a readable skill. And so it is little wonder really that – as has been pointed out by some people, especially those who adhere to some of the various conspiracy theories doubting Shakespeare's authorship of his works – William Shakespeare's handwriting, going by the very few samples of it we have, to us today looks really quite spidery, unruly, and messy, even though he is of course an extremely experienced writer by hand in ink with a quill. But he is also extremely prolific and therefore writes – as we have also noted – very fast. The fact that Shakespeare characterises the poet and their poetry as 'modern' is also telling: Shakespeare uses the adjective much as we do today, to mean 'contemporary', 'up-to-date', 'of our time'. But as with some users of the word today, to him it mostly brings a dismissive note, as in 'new-fangled', 'fashionable but not properly established'. And it ties in here with Shakespeare's general wariness, expressed on several occasions, not least again recently in Sonnet 76, of "new-found methods" and "compounds strange." But of course, Shakespeare here includes himself in the entity 'modern quill', as his writing too would come short speaking of the worth that 'grows' in the young man, and this presents another fascinating oddity about this line: Speaking of worth, what worth in you doth grow. It echoes the construction earlier on of "I found, or thought I found," and in doing so very subtly suggests a shade of doubt, a moment of hesitation that then requires new emphasis. Whether Shakespeare does this deliberately or whether he does it instinctively and subconsciously, we can't even be certain, but it is this one of these instances where the writing draws attention to itself, and this, as we have noted before, with any writer of prolific mastery, tends to happen for a reason. |

|

This silence for my sin you did impute

|

You interpret this silence of mine as a sin and therefore attach a guilt or a blame to it.

Both 'sin' and 'impute' have strongly religious connotations, whereby 'impute' means "to lay the responsibility or blame for (something) often falsely or unjustly," (Merriam-Webster) and with this sense of an unfair or unjust attribution of blame or guillt, Shakespeare sets up his now ensuing claim: |

|

Which shall be most my glory, being dumb,

|

This 'sin', as you see it, this being dumb, shall be most my glory, meaning it shall be most in my favour, my greatest achievement, so to speak.

And this is closer to the truth than even Shakespeare may at the time have been aware: never describing the young man and thus allowing him to almost entirely live in our imagination turns out to have been, indeed, a stroke of genius. Because our imagination can paint a perfect picture of him, whereas even Shakespeare's words wouldn't be able to do so, not least because of course beauty lives in the eye of the beholder, and each of us beholds beauty differently. And by not giving us his impression of what beauty is, he allows us to experience his perception of the young man. It is the only way this can be achieved. 'Dumb' here, as generally at the time and as the next line makes clear, means 'mute', not, as American slang has it today, 'stupid'. |

|

For I impair not beauty, being mute,

When others would give life and bring a tomb. |

Because I, being thus mute, do not damage or weaken beauty – here of course specifically your beauty – when other poets set out to bring this beauty to life in their poetry, but actually end up killing it.

In other words, by remaining silent about your beauty, I do not represent it in an inadequate way and thus I cannot do it injustice or even damage it. Other poets, writing about it in their by necessity inadequate terms – because all language is inadequate when talking about your qualities – may have the best of intentions and seek to bring your beauty to life in our minds by describing it, but in doing so they actually just kill it off. |

|

There lives more life in one of your fair eyes

Than both your poets can in praise devise. |

Because, and this sums it all up: there lives more life in just one of your beautiful eyes than both of your poets can ever come up with in their attempts at praising you with their poetry.

And while theoretically "both your poets" could mean both your other poets, editors are pretty much in agreement, as am I, that this is Shakespeare still including himself in the equation and that therefore these two poets here referred to are he himself and one other, rival, poet. The fact that he talks about 'others' just above does not detract from this, since the plural here, much as we discussed with Sonnet 78, is more than likely used generically and somewhat dismissively of the presence of any other poet in the young man's orbit. |

Sonnet 83 picks up on the notion, introduced in Sonnet 82, of a 'gross painting' in words that other poets make of the young man with the 'strained touches' that rhetoric can lend them, in stark contrast to Shakespeare's own 'plain true words'. But rather than forming a contained pair with Sonnet 82, it spins the argument further, now giving his reasons for not doing what other poets pursue, namely the fanciful portrayal of the young man in the most elaborate and fashionable language available at the time. Shakespeare then continues to build on this for another two sonnets, to effectively create a group within a group that follows one continuous thread right through to and including Sonnet 85, before he then ends the Rival Poet sequence on an astonishing flourish with Sonnet 86.

When with Sonnet 82 we observed how Shakespeare's tone had changed from frivolity and wit to what I tentatively described as a 'resigned sulk', then perhaps the most notable thing about Sonnet 83 is that with this poem, he is starting to fight back. Or rather, he is setting out the argument in his defence, begun most obviously with the closing couplet of Sonnet 82, but really with the sestet of that sonnet. The sestet, you may know, or remember if you were with me when I welcomed my first special guest, Professor Stephen Regan to discuss the sonnet in principle, consists of the last six lines, and forms the second part of a sonnet, following the first part, which is formed by the octave, consisting of the first eight lines.

Here is a reminder of what happened: the octave of Sonnet 82 tells the young man that because of his exalted status, and having never made a formal commitment to Shakespeare, he is not only allowed, but effectively forced to look around for new, fresh poets to praise his great worth. With the sestet, Shakespeare starts setting out his own stall once more:

And do so love, yet when they have devised

What strained touches rhetoric can lend,

Thou, truly fair, wert truly sympathised

In true, plain words by thy true-telling friend,

And their gross painting might be better used

Where cheeks need blood, in thee it is abused.

Already the sulk is starting to make way for a new-found confidence, which now grows, and it grows in a curiously rhythmic spiral, in which Shakespeare uses several patterns of repetition.

In classical rhetoric – and this entire argument, stretching from Sonnet 82 through Sonnet 85 is entirely steeped in the ancient art of rhetoric – repetition for rhythmic effect and semantic purpose and emphasis is called anaphora, and Shakespeare uses it throughout his works, as most poets do.

But here he does something special with it: he sets it up in the opening two lines of the poem, with 'painting', which also provides the direct link to Sonnet 82. He then immediately consolidates and also subverts it in the third line with his highly unusual mental double take of "I found, or thought I found..." — The repetition here does the opposite of what one might naturally expect. Rather than emphasise and drive home further the point being made, it lowers the level of certainty. Instead of saying, 'I found this to be so and finding it to be so I was certain', it suggests: 'I found this to be so, or rather I was under the impression of finding it so, but I might be wrong about this'.

Then we have four lines with nothing happening rhetorically that could be alleged to be particularly noteworthy, until line eight when the anaphora now again is deployed ostensibly to strengthen the argument, but actually weakens it in a quite a startlingly subversive way: "Speaking of worth, what worth in you doth grow."

On the surface, this sounds like Shakespeare is simply specifying, clarifying the 'worth' he is talking about, but the effect it has – and we must always be open to the possibility of course that our sensitivities to the language and our way of hearing things may to some extent differ from how William Shakespeare and his contemporaries heard it – the effect it has is to sow a reasonable doubt about the integrity of this worth, because the line can be read in two decidedly distinct ways:

a) 'Speaking of worth and I mean of course the excellent worth that grows in and with you as you yourself grow older and ever wiser and more worthy, and your external beauty is gradually absorbed into the beautiful character of your being', or

b) 'Speaking of worth, insofar as, or to the extent to which, it grows in you. At all, as one might feel tempted to add...'

The two readings are almost diametrically opposed in terms of their attitude to the recipient, and of course this is not the first time we have witnessed Shakespeare thus being torn. When his young lover had his fling with Shakespeare's mistress, Shakespeare told him, in Sonnet 35:

Such civil war is in my love and hate

That I an accessary needs must be

To that sweet thief which sourly robs from me.

Next in Sonnet 83, Shakespeare does something similarly unusual and therefore eye-catching. Instead of going for a straightforward anaphora, for which he has now established first a precedent, then a subverted reiteration and then a confirmation of the subverted reiteration, he now repeats a construction and a concept, but not the word:

Which shall be most my glory, being dumb,

For I impair not beauty, being mute,

And again we are invited, so as not to say strong-armed, to ask: what, Will, would you with these words? The first of these two lines is not overly puzzling: although Shakespeare has just spelt out that it is his silence which the young man imputes for his sin, clarifying here that it is not being so imputed or the imputation as a sin that I will claim as my glory, but my silence, my being dumb, makes sense: one wants to not give rise to a misunderstanding in such matters and open oneself to any charges of revelling in having one's reputation tarnished.

In the second line, though, "being mute" is really entirely unnecessary, except for the syllable count and the rhyme, but Shakespeare has it in his powers and wit to find syllables and rhymes when he needs them that also carry meaning, often on multiple levels, as often we have seen, and that make for a prosodic music of poetry. Not so much so here. And that means he's either having a bad poetry day or he is drawing our attention to something. And while it is not outwith the bounds of possibility that even our Will may have a bad poetry day now and then, I am inclined to lean towards the latter of these two explanations, even if, as is also entirely possible, he isn't actually doing so consciously.

Because the effect the repetition here has is that it appears to mildly mock the accusation. This is something you find people do in everyday life and language. If you say to somebody: 'You don't talk much, do you? Perhaps it would be good if you could occasionally contribute to a conversation when we're having Janice and Ted round for dinner', they could of course simply shrug their shoulders and say: 'kay'. Or they could do what Shakespeare does: 'Oh I'm the quiet one, am I? Well, you know, maybe being quiet isn't such a bad thing. At least, being silent I don't spout such ardent nonsense as these supposed friends of ours who haven't the faintest idea what they're talking about'...

And so what it may boil down to, and I personally rather like this idea, is not so much William Shakespeare standing by his desk in his study, looking out of the window upon the alleyway bustling with Londoners going about their business and pondering how best shall I deploy anaphora today, but our Will being essentially human, genuinely peeved, and also not a little annoyed that he keeps having to justify and explain himself, and writing his response to his young love just as one would say it, only better and in the format of an iambic rhyming pentameter over the fourteen structurally sound lines of a sonnet.

And of course there is one more of these repetitions in the closing couplet, though here he once more varies the type, now going for the same concept in an alliterative word pair consisting of verb and corresponding noun:

There lives more life in one of your fair eyes

Than both your poets can in praise devise.

This too works on two levels: it functions both as high praise indeed and also as an effective putdown. Because it once again on the surface level says to the young man: your eyes are the wondrous windows to your soul and so in one of them alone there lives more of you, your spirit, your beauty both external and internal than both of us poets could ever do justice to in our writing, but it also at the very same time says to him: this is just stating the obvious. And you're being vain and unreasonable and conceited to expect me to say more: you should really know better by now.

And this new level of assertiveness that here shines through – more subliminal than explicit – in the next poem, in Sonnet 84, will find direct and unmistakable expression, because William Shakespeare is not done with taking the stand in his own defence: he has only just set forth opening statement..

When with Sonnet 82 we observed how Shakespeare's tone had changed from frivolity and wit to what I tentatively described as a 'resigned sulk', then perhaps the most notable thing about Sonnet 83 is that with this poem, he is starting to fight back. Or rather, he is setting out the argument in his defence, begun most obviously with the closing couplet of Sonnet 82, but really with the sestet of that sonnet. The sestet, you may know, or remember if you were with me when I welcomed my first special guest, Professor Stephen Regan to discuss the sonnet in principle, consists of the last six lines, and forms the second part of a sonnet, following the first part, which is formed by the octave, consisting of the first eight lines.

Here is a reminder of what happened: the octave of Sonnet 82 tells the young man that because of his exalted status, and having never made a formal commitment to Shakespeare, he is not only allowed, but effectively forced to look around for new, fresh poets to praise his great worth. With the sestet, Shakespeare starts setting out his own stall once more:

And do so love, yet when they have devised

What strained touches rhetoric can lend,

Thou, truly fair, wert truly sympathised

In true, plain words by thy true-telling friend,

And their gross painting might be better used

Where cheeks need blood, in thee it is abused.

Already the sulk is starting to make way for a new-found confidence, which now grows, and it grows in a curiously rhythmic spiral, in which Shakespeare uses several patterns of repetition.

In classical rhetoric – and this entire argument, stretching from Sonnet 82 through Sonnet 85 is entirely steeped in the ancient art of rhetoric – repetition for rhythmic effect and semantic purpose and emphasis is called anaphora, and Shakespeare uses it throughout his works, as most poets do.

But here he does something special with it: he sets it up in the opening two lines of the poem, with 'painting', which also provides the direct link to Sonnet 82. He then immediately consolidates and also subverts it in the third line with his highly unusual mental double take of "I found, or thought I found..." — The repetition here does the opposite of what one might naturally expect. Rather than emphasise and drive home further the point being made, it lowers the level of certainty. Instead of saying, 'I found this to be so and finding it to be so I was certain', it suggests: 'I found this to be so, or rather I was under the impression of finding it so, but I might be wrong about this'.

Then we have four lines with nothing happening rhetorically that could be alleged to be particularly noteworthy, until line eight when the anaphora now again is deployed ostensibly to strengthen the argument, but actually weakens it in a quite a startlingly subversive way: "Speaking of worth, what worth in you doth grow."

On the surface, this sounds like Shakespeare is simply specifying, clarifying the 'worth' he is talking about, but the effect it has – and we must always be open to the possibility of course that our sensitivities to the language and our way of hearing things may to some extent differ from how William Shakespeare and his contemporaries heard it – the effect it has is to sow a reasonable doubt about the integrity of this worth, because the line can be read in two decidedly distinct ways:

a) 'Speaking of worth and I mean of course the excellent worth that grows in and with you as you yourself grow older and ever wiser and more worthy, and your external beauty is gradually absorbed into the beautiful character of your being', or

b) 'Speaking of worth, insofar as, or to the extent to which, it grows in you. At all, as one might feel tempted to add...'

The two readings are almost diametrically opposed in terms of their attitude to the recipient, and of course this is not the first time we have witnessed Shakespeare thus being torn. When his young lover had his fling with Shakespeare's mistress, Shakespeare told him, in Sonnet 35:

Such civil war is in my love and hate

That I an accessary needs must be

To that sweet thief which sourly robs from me.

Next in Sonnet 83, Shakespeare does something similarly unusual and therefore eye-catching. Instead of going for a straightforward anaphora, for which he has now established first a precedent, then a subverted reiteration and then a confirmation of the subverted reiteration, he now repeats a construction and a concept, but not the word:

Which shall be most my glory, being dumb,

For I impair not beauty, being mute,

And again we are invited, so as not to say strong-armed, to ask: what, Will, would you with these words? The first of these two lines is not overly puzzling: although Shakespeare has just spelt out that it is his silence which the young man imputes for his sin, clarifying here that it is not being so imputed or the imputation as a sin that I will claim as my glory, but my silence, my being dumb, makes sense: one wants to not give rise to a misunderstanding in such matters and open oneself to any charges of revelling in having one's reputation tarnished.

In the second line, though, "being mute" is really entirely unnecessary, except for the syllable count and the rhyme, but Shakespeare has it in his powers and wit to find syllables and rhymes when he needs them that also carry meaning, often on multiple levels, as often we have seen, and that make for a prosodic music of poetry. Not so much so here. And that means he's either having a bad poetry day or he is drawing our attention to something. And while it is not outwith the bounds of possibility that even our Will may have a bad poetry day now and then, I am inclined to lean towards the latter of these two explanations, even if, as is also entirely possible, he isn't actually doing so consciously.

Because the effect the repetition here has is that it appears to mildly mock the accusation. This is something you find people do in everyday life and language. If you say to somebody: 'You don't talk much, do you? Perhaps it would be good if you could occasionally contribute to a conversation when we're having Janice and Ted round for dinner', they could of course simply shrug their shoulders and say: 'kay'. Or they could do what Shakespeare does: 'Oh I'm the quiet one, am I? Well, you know, maybe being quiet isn't such a bad thing. At least, being silent I don't spout such ardent nonsense as these supposed friends of ours who haven't the faintest idea what they're talking about'...

And so what it may boil down to, and I personally rather like this idea, is not so much William Shakespeare standing by his desk in his study, looking out of the window upon the alleyway bustling with Londoners going about their business and pondering how best shall I deploy anaphora today, but our Will being essentially human, genuinely peeved, and also not a little annoyed that he keeps having to justify and explain himself, and writing his response to his young love just as one would say it, only better and in the format of an iambic rhyming pentameter over the fourteen structurally sound lines of a sonnet.

And of course there is one more of these repetitions in the closing couplet, though here he once more varies the type, now going for the same concept in an alliterative word pair consisting of verb and corresponding noun:

There lives more life in one of your fair eyes

Than both your poets can in praise devise.

This too works on two levels: it functions both as high praise indeed and also as an effective putdown. Because it once again on the surface level says to the young man: your eyes are the wondrous windows to your soul and so in one of them alone there lives more of you, your spirit, your beauty both external and internal than both of us poets could ever do justice to in our writing, but it also at the very same time says to him: this is just stating the obvious. And you're being vain and unreasonable and conceited to expect me to say more: you should really know better by now.

And this new level of assertiveness that here shines through – more subliminal than explicit – in the next poem, in Sonnet 84, will find direct and unmistakable expression, because William Shakespeare is not done with taking the stand in his own defence: he has only just set forth opening statement..

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!