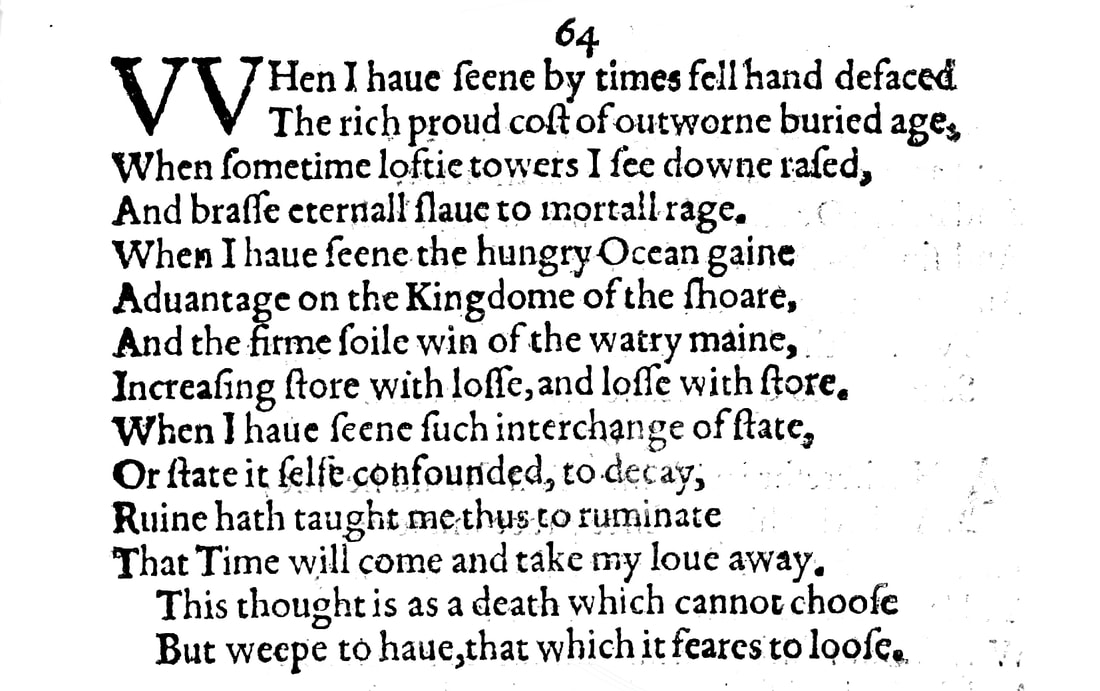

Sonnet 64: When I Have Seen by Time's Fell Hand Defaced

|

When I have seen by time's fell hand defaced

The rich proud cost of outworn buried age; When sometime lofty towers I see downrazed And brass eternal slave to mortal rage; When I have seen the hungry ocean gain Advantage on the kingdom of the shore, And the firm soil win of the watery main, Increasing store with loss and loss with store; When I have seen such interchange of state, Or state itself confounded to decay, Ruin hath taught me thus to ruminate: That time will come and take my love away. This thought is as a death which cannot choose But weep to have that which it fears to lose. |

|

When I have seen by time's fell hand defaced

The rich proud cost of outworn buried age, |

When I have seen how cruel or ruthless time defaces or damages the lavish, extravagantly splendid and also flashy, showy, perhaps ostentatious objects that were once expensive and are now worn out with their age and buried in forgotten and disused oblivion...

In other words: when I see how time by and by lets everything disintegrate and ultimately decay, even things we once valued greatly and paid a high price for. The applicable dictionary definition of 'fell' is: "of terrible evil or ferocity; deadly." (Oxford Languages) We don't really see it used as an adjective in that sense any more today, but a remnant of it resides in the phrase 'in one fell swoop', although for us it no longer has necessarily bad or evil connotations. |

|

When sometime lofty towers I see downrazed

|

When I see lofty – for which read tall, but also 'proud' and again ostentatious, showy – towers razed to the ground. Implied is that they are razed to the ground also by the ravages of time itself or indeed by the adversities that come over time, such as falling into disuse, or prey to the consuming force of fire, or to a hostile power laying siege to a town and damaging tall structures to the point where they collapse.

The 'sometime' here can be read as either belonging to the lofty towers, so they are towers that were at one time lofty but are now razed to the ground, or as belonging to the instance of seeing, as in: when from time to time I come across a once lofty tower that has been razed to the ground. The fact alone though that the tower so imagined is now no longer standing suggests that – while a secondary meaning may be entirely intended – the primary meaning really has to be the former: when I see towers that were at some time in the past lofty now razed to the ground. |

|

And brass eternal slave to mortal rage;

|

And when I see brass – which is meant to be a durable material – be slave to the forces of deadly destruction, which, as always is brought about by time itself.

'Eternal' also offers two possible readings, both of which may be intentional: either as an adjective belonging to brass, in the sense of brass eternal, placed after the noun it describes, the way we would use 'arrogance supreme', for example, or as an adjective to describe the kind of slave it becomes, as in an eternal slave. Editors in fact also refer to it in this latter context as an adverb, in the sense of brass being 'eternally' slave to mortal rage. |

|

When I have seen the hungry ocean gain

Advantage on the kingdom of the shore, |

When I have seen how the ocean, hungry as it is because it is forever lapping on the land, gain advantage, meaning win over the kingdom of the shore by swallowing up land and turning previously firm soil into sea...

|

|

And the firm soil win of the watery main,

|

...and when I have seen the firm soil in turn at other times and in other places encroach on the sea, for example when a volcano erupts and suddenly creates an island, or over time by depositing silt and 'taking back' land, as it were.

|

|

Increasing store with loss and loss with store;

|

And in this everlasting battle one loses and the other gains and then the losses and gains are reversed.

Shakespeare underlines the grand futility of this continuous exchange by allowing the 'store' or gain to be 'increased' with loss and the loss to be increased with gain, so there is no real gain and no real loss because both increase each other in an eternal cycle that is forever undone. |

|

When I have seen such interchange of state,

Or state itself confounded to decay, |

When I have observed such a continuous exchange of states, meaning conditions or states of being – land turning into sea, sea turning into land – or indeed state itself, for which here read the institutions of the state, kingdoms, courts, entire political constructs, the great empires themselves, ruined to utter decay and thus nonexistence.

We noted very recently, in the last episode on Sonnet 63, the numerous uses of 'confound' to mean variants of 'destroy'. 'State' in the second line here can also, additionally, of course be read as simply the condition of being, whereby the line then turns into a summary of how everything that is in a state of being ultimately surrenders to decay. Nothing speaks against Shakespeare aiming for this double meaning, but here we have another close reference to Arthur Golding's translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses that would appear to have strongly influenced Will in composing his own verse: Even so have places oftentimes exchanged their state, For I have seen it sea which was substantial ground alate, Again where sea was, I have seen the same become dry land, And shells and scales of seafish far have lain from any strand, And in the tops of mountains high old anchors have been found. (XV.287-9 in Golding) 'Alate' means 'before', as in 'which was substantial ground before'. |

|

Ruin hath taught me thus to ruminate:

That time will come and take my love away. |

Having seen, watched, and observed all this, its common feature, ruin, has taught me to ponder the following thought: time will come and take my love away, whereby 'love' here stands for the lover, although if the lover is gone then so, of course, is love.

|

|

This thought is as a death which cannot choose

But weep to have that which it fears to lose. |

This thought – that time will come and take my love away – is like a death to me, and this thought – the which in the first line – cannot help but weep at having something that it fears to lose. The thought here becomes synonymous with the writer, because it is I, the poet, of course, who weeps at the thought of losing my love.

|

With his moving, melancholy Sonnet 64, William Shakespeare continues an ongoing meditation on time, but unlike other sonnets that have gone before or that are soon to come, he here finds no redemption in his own writing or hope in the prospect of being able to lend his lover longevity beyond his presence on the planet through poetry. The sonnet thus offers the perhaps most profoundly troubled perspective yet on the passing of time and with its sincerity paves the way for further heartfelt articulations of what it is to be William Shakespeare in a world where things go awry.

We find our Will in a frame of mind here that has started to take a dim view of life. Since Sonnet 60, a tone and a mood have begun to take hold which more than hint at William Shakespeare not being in a happy place, and Sonnet 64 makes him sound saddest so far. As with every other sonnet we have looked at, we cannot know what exactly it is that brings on this fatigue; what we can say is that both tone and mood, much as the theme, of Sonnet 64 sit snugly embedded in a group of similarly 'atmosphered' sonnets that support each other and reveal much the same preoccupations.

We have already on several previous occasions tried to formulate a framework, if that's the right word, for the kind of conditions that may lead a poet like Shakespeare to get so agitated about his age, about the evident age difference between him and his young lover, and about a passing of time that he seems to be experiencing more and more urgently as time simply running out. One of the possible reasons we have put forward is his either rapidly advancing on, or having just stepped across, the to many a man meaningful threshold of 30, an age which in terms of life expectancy in the late 16th century would have been the approximate equivalent to someone hitting 50, or even 60, today.

It would be tempting now, with Shakespeare reaching this nadir in his disposition, to delve further into the timing of the sonnets and how they can be brought into a coherent constellation with known events in Shakespeare's life – including him reaching easily established age milestones at a given time – but if we hold on to this thought for a little while longer, we will once more be richly rewarded, because over the next few sonnets we shall see Shakespeare go through a profound crisis in multiple respects, and this will prove to be of great significance for our understanding not only of Shakespeare, the man, and of his relationship with the young lover, but very specifically also of the timeframe we are most likely dealing with. But we will come back to this and we will also at that point be able to draw together a few fascinating external facts which we have not before seen fit to bring into the equation, but which in the context of what is about to unfold will be increasingly relevant and therefore impossible to ignore.

Sonnet 64 is easily one of my favourite sonnets of them all, mostly because it shows us Shakespeare at his most vulnerable and bare. There is no flattering the young man here, there is no elevating his own writing or deprecating it for poetic effect. There is no hyperbole and no demonstrative cleverness. There is, yes, great dexterity, of course, and there are some instances where, as we noted earlier, a line or a word may have more than one meaning, but even where that's the case, there is really nothing performative about it all: Shakespeare with Sonnet 64 does not appear to set out to prove anything or to impress anyone, to win any favour or to "plead," as he called it in Sonnet 23 "for love."

The sonnet doesn't even come across as necessarily meant for anyone other than the poet himself to know of and read. About this, we cannot even speculate: there is virtually nothing that can tell or even suggest to us whether Shakespeare ever showed or read or sent this to anyone, including the young man – or anyone else for that matter – here referred to. On its own – and the poem can absolutely stand on its own and is not paired strongly to either Sonnet 63 or Sonnet 65 – this sonnet doesn't 'go' anywhere, it finds no resolution: its conclusion, such as it is, does not 'solve' anything.

This changes somewhat if we take it in its setting within the collection and view it as, if not paired with, then certainly linked to, both Sonnet 63 and Sonnet 65. Doing so shows us something of a vector that leads us all the way from Sonnet 60, which initiates the theme of time for this group, past Sonnet 61 which really has a different primary concern that is not directly related to this, through the self-knowledge and supposed self-love of Sonnet 62, into Sonnet 63 which contrasts Will's own age and state of being with that of the young man and presents poetry as the means to forestall the young man turning into what would otherwise be his fate: one day being as old and wrinkled as Will, from there into this realisation that, the power of poetry notwithstanding, time will still spell an end at one point to the love that is now alive, and into Sonnet 65 which then no longer asserts that the verse of Shakespeare will keep the young man alive, but invokes this as a 'miracle' that can at best be hoped and wished, perhaps in a way also prayed, for.

For this reason alone, and, beyond that because there is no good reason to do otherwise, it makes sense to read Sonnet 64 as part of this group that has its own internal, if subtle, trajectory. This also, and quite incidentally, 'solves' the 'issue', if one were to consider it such, that Sonnet 64 is another one of those sonnets which could in theory be about anyone. On the surface and in isolation, this is of course true: nowhere in the sonnet do we learn who this 'love' is that time will take away from our Will. But in its natural, logical, and therefore entirely plausible context, the question answers itself: it is in all reasonable likelihood about the same love as Sonnet 63, which we know for certain is a young man.

If Sonnet 64 suggests that things are not so good right now, they are about to get a whole lot worse, but not immediately: Sonnet 65, as just outlined, can be thought of as essentially a continuation of this consideration on time, but with Sonnet 66 William Shakespeare blasts open a door into a region of his mind that we have not yet visited, and there – in the spatial and temporal aftermath, so to metaphorically speak – introduces us to a whole new league of lament and foreboding...

We find our Will in a frame of mind here that has started to take a dim view of life. Since Sonnet 60, a tone and a mood have begun to take hold which more than hint at William Shakespeare not being in a happy place, and Sonnet 64 makes him sound saddest so far. As with every other sonnet we have looked at, we cannot know what exactly it is that brings on this fatigue; what we can say is that both tone and mood, much as the theme, of Sonnet 64 sit snugly embedded in a group of similarly 'atmosphered' sonnets that support each other and reveal much the same preoccupations.

We have already on several previous occasions tried to formulate a framework, if that's the right word, for the kind of conditions that may lead a poet like Shakespeare to get so agitated about his age, about the evident age difference between him and his young lover, and about a passing of time that he seems to be experiencing more and more urgently as time simply running out. One of the possible reasons we have put forward is his either rapidly advancing on, or having just stepped across, the to many a man meaningful threshold of 30, an age which in terms of life expectancy in the late 16th century would have been the approximate equivalent to someone hitting 50, or even 60, today.

It would be tempting now, with Shakespeare reaching this nadir in his disposition, to delve further into the timing of the sonnets and how they can be brought into a coherent constellation with known events in Shakespeare's life – including him reaching easily established age milestones at a given time – but if we hold on to this thought for a little while longer, we will once more be richly rewarded, because over the next few sonnets we shall see Shakespeare go through a profound crisis in multiple respects, and this will prove to be of great significance for our understanding not only of Shakespeare, the man, and of his relationship with the young lover, but very specifically also of the timeframe we are most likely dealing with. But we will come back to this and we will also at that point be able to draw together a few fascinating external facts which we have not before seen fit to bring into the equation, but which in the context of what is about to unfold will be increasingly relevant and therefore impossible to ignore.

Sonnet 64 is easily one of my favourite sonnets of them all, mostly because it shows us Shakespeare at his most vulnerable and bare. There is no flattering the young man here, there is no elevating his own writing or deprecating it for poetic effect. There is no hyperbole and no demonstrative cleverness. There is, yes, great dexterity, of course, and there are some instances where, as we noted earlier, a line or a word may have more than one meaning, but even where that's the case, there is really nothing performative about it all: Shakespeare with Sonnet 64 does not appear to set out to prove anything or to impress anyone, to win any favour or to "plead," as he called it in Sonnet 23 "for love."

The sonnet doesn't even come across as necessarily meant for anyone other than the poet himself to know of and read. About this, we cannot even speculate: there is virtually nothing that can tell or even suggest to us whether Shakespeare ever showed or read or sent this to anyone, including the young man – or anyone else for that matter – here referred to. On its own – and the poem can absolutely stand on its own and is not paired strongly to either Sonnet 63 or Sonnet 65 – this sonnet doesn't 'go' anywhere, it finds no resolution: its conclusion, such as it is, does not 'solve' anything.

This changes somewhat if we take it in its setting within the collection and view it as, if not paired with, then certainly linked to, both Sonnet 63 and Sonnet 65. Doing so shows us something of a vector that leads us all the way from Sonnet 60, which initiates the theme of time for this group, past Sonnet 61 which really has a different primary concern that is not directly related to this, through the self-knowledge and supposed self-love of Sonnet 62, into Sonnet 63 which contrasts Will's own age and state of being with that of the young man and presents poetry as the means to forestall the young man turning into what would otherwise be his fate: one day being as old and wrinkled as Will, from there into this realisation that, the power of poetry notwithstanding, time will still spell an end at one point to the love that is now alive, and into Sonnet 65 which then no longer asserts that the verse of Shakespeare will keep the young man alive, but invokes this as a 'miracle' that can at best be hoped and wished, perhaps in a way also prayed, for.

For this reason alone, and, beyond that because there is no good reason to do otherwise, it makes sense to read Sonnet 64 as part of this group that has its own internal, if subtle, trajectory. This also, and quite incidentally, 'solves' the 'issue', if one were to consider it such, that Sonnet 64 is another one of those sonnets which could in theory be about anyone. On the surface and in isolation, this is of course true: nowhere in the sonnet do we learn who this 'love' is that time will take away from our Will. But in its natural, logical, and therefore entirely plausible context, the question answers itself: it is in all reasonable likelihood about the same love as Sonnet 63, which we know for certain is a young man.

If Sonnet 64 suggests that things are not so good right now, they are about to get a whole lot worse, but not immediately: Sonnet 65, as just outlined, can be thought of as essentially a continuation of this consideration on time, but with Sonnet 66 William Shakespeare blasts open a door into a region of his mind that we have not yet visited, and there – in the spatial and temporal aftermath, so to metaphorically speak – introduces us to a whole new league of lament and foreboding...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!