Sonnet 61: Is it Thy Will Thy Image Should Keep Open

|

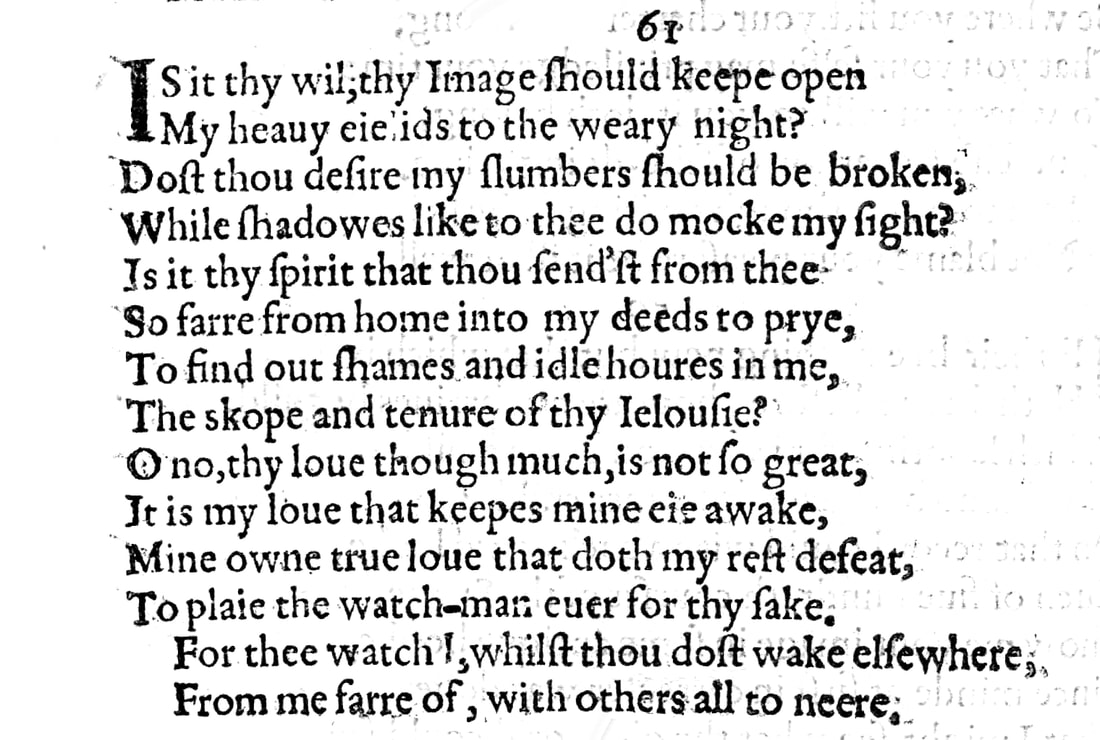

Is it thy will thy image should keep open

My heavy eyelids to the weary night? Dost thou desire my slumbers should be broken While shadows like to thee do mock my sight? Is it thy spirit that thou sendst from thee So far from home into my deeds to pry To find out shames and idle hours in me, The scope and tenure of thy jealousy? O no, thy love, though much, is not so great: It is my love that keeps mine eye awake, Mine own true love that doth my rest defeat To play the watchman ever for thy sake. For thee watch I, whilst thou dost wake elsewhere, From me far off, with others all too near. |

|

Is it thy will thy image should keep open

My heavy eyelids to the weary night? |

Is it your intention that your image should keep me from sleep, tired though I am?

It is tempting to interpret the 'image' in question as a vision of the young man in Shakespeare's imagination, but that appears to be dealt with in the next couple of lines, whereas this opener, which does after all speak of eyes being kept open, quite plausibly refers to an actual image, such as a miniature portrait of the young man that may be in the poet's possession. How we read the line mostly depends on how literally we want to take what is being said. If the image is a physical picture, then the writer's eyes are physically 'kept open', because he can't sleep and has to keep looking at it; if the image is a figment of his imagination, then his eyes are 'kept open' metaphorically in as much as he can't get to sleep, because the moment he actually opens his yes, the vision would, of course, disappear. That the poet is tired is established by the eyelids being heavy on the one hand and by the night being weary on the other: Will's weariness is transferred to the night which is experienced as tired and needful of rest. These opening lines of Sonnet 61 provide a direct reference to Sonnet 27: Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed The dear repose for limbs with travel tired and much as then we are told in this sonnet too that William Shakespeare and his lover are apart, although unlike Sonnets 27 & 28, or Sonnets 50 & 51, this poem would appear to suggest that it is in fact the young man who has gone away, as we are about to see... |

|

Dost thou desire my slumbers should be broken

While shadows like to thee do mock my sight? |

Do you wish that my sleep is interrupted while visions of you appear to me and mock my sight because you are not, obviously, here.

This now clearly refers to images of the young man that appear in Shakespeare's imagination as apparitions or indeed dreams that then wake him up. We have seen the use of 'shadows' to mean exactly the same thing before, again in Sonnet 27: Save that my soul's imaginary sight Presents thy shadow to my sightless view, And then again in Sonnet 43: Then thou, whose shadow shadows doth make bright, How would thy shadow's form form happy show To the clear day with thy much clearer light, When to unseeing eyes thy shade shines so? |

|

Is it thy spirit that thou sendst from thee

So far from home into my deeds to pry |

Are you sending me your spirit – which here may be understood visually as the image in Shakespeare's imagination, the apparition, or more generally as the young man's keen and curious thoughts – from whereever you are, so far from home, to pry into what I am doing...

This is the first indication we get that it is the young man on this occasion who is absent 'from home', though this is not wholly conclusive, it is entirely possible that Shakespeare relates the phrase 'so far from home' to himself. |

|

To find out shames and idle hours in me,

|

...to find out whether I am up to shameful or illicit or reprehensible behaviour, whiling away my time with being idle, for which here read getting up to no good. The expression for Shakespeare is almost certainly inspired by the proverbial notion that idle hands are the devil's workshop or the devil finds work for idle hands and so here very decidedly 'shame' and 'idle hours' go hand in hand.

|

|

The scope and tenure of thy jealousy?

|

And this, my conduct, or, to be more precise, your concern and worry about my conduct is the 'scope and tenure' of your jealousy.

'Scope' is easier to understand here than 'tenure', as it simply refers to the domain or extent to which your jealousy, as it is in this case, reaches. 'Tenure' by many editors gets emended to 'tenor' which then makes it "the general meaning, sense, or content of something" (Oxford Languages), which makes a degree of sense, especially if we read it as 'the content' and therefore cause of your jealousy. But 'tenure' could also be applied, for instance in the sense of a "period during which an office is held" (Oxford) which would then give it a temporal sense to complement the spatial sense of 'scope'; and Shakespeare also uses 'tenure', spelt 'tenour' to mean a contract or legally binding agreement, in which case it would convey the sense that the young man is entirely entitled to his jealousy, and this is a particularly attractive reading of the word here, since we know that Shakespeare a) reverts to legalese every so often to make a complex argument, and b) ascribes to the young man an elevated status that comes with clearly defined privileges, as well as many rather less clearly defined ones. For this reason I have elected to leave 'tenure' here as it is in the Quarto Edition. |

|

O no, thy love, thou much, is not so great:

|

Oh no: that is not what it is because your love, although there is much of it, or although it has much going for it, is not actually as great as all that; certainly, not, as is implied here, so great as to make you jealous to the extent that you care about what I am up to when I am away from you or you – as seems more likely the case going by the closing couplet – away from me.

|

|

It is my love that keeps mine eye awake,

Mine own true love that doth my rest defeat |

It is my own love for you that keeps me awake and defeats my rest, meaning prevents me from getting any sleep...

|

|

To play the watchman ever for thy sake.

|

...while I play the watchman because of you.

A watchman was a common feature of an Elizabethan town or city, to patrol and guard the place at night against robbers, thieves or other unruly or indeed unlawful behaviour, and editors point to the proverb "one good friend watches for another," which Shakespeare is likely to have been familiar with. Having to play the watchman for the young lover's sake carries its own ambiguity – a feature we have noted on several occasions before in relation to the young man – as it could be read on the one hand to mean, I have to watch out for you, to protect your safety, or, on the other hand, which seems a great deal more plausible in this instance, since you are out and about I have to watch out and keep an eye on you to make sure you are not up to any wrongdoing, thus placing the young man not in the role of the lover who needs to be protected, but of the person of whom others, including Shakespeare himself, have to be wary, in this case of course not so much because he is likely to attack or rob them, but because he seems to be intent on conducting relationships with them that Shakespeare disapproves of and that make him, Shakespeare, jealous. |

|

For thee watch I, whilst thou dost wake elsewhere

From me far off, with others all too near. |

It is for you that I watch out, while you are awake elsewhere, far away from me, with other people all too near around you.

And in these others being 'all too near' the young man is very strongly implied that he is conducting romantic or sexual affairs with them, because virtually nothing else could in any way be considered to be Shakespeare's business, and even the fact that he expresses himself so clearly here marks a noteworthy change in tone from previous sonnets... |

With Sonnet 61, William Shakespeare returns to the theme treated in Sonnets 27 & 28 of an enforced separation from his lover that robs him of his sleep, but here brings into the equation the young man's hoped for but absent jealousy, to end on a notion that in fact betrays Shakespeare's own jealousy of the company the young man is keeping while away from him, something that we saw foreshadowed strongly in Sonnet 48. The sonnet thus echos several of the concerns that have preoccupied our poet from the pair 27 & 28 onwards, right through to Sonnet 51, including the triangular constellation that starts with Sonnet 33 and seems to be resolved, at least for the time-being, with Sonnet 42. This justifiably poses the question whether Sonnet 61 may not indeed have been composed around the same time and be part of the same period of separation, which would support the thesis that at this point the collection falls out of sequence, as is the contention of many scholars.

Always and forever bearing in mind that we can say nothing about these sonnets with any certainty and that virtually everything about them is conjecture, except the words, this is a particularly apt point in the proceedings to focus on what the words themselves tell us and simply add any insights we may gain from them to our 'depository', so to speak, of evidence, long before attempting to reach any kind of conclusion.

What the words unequivocally and really beyond any doubt convey to us is that:

- The poet is experiencing sleepless nights because he is seeing, either in a physical picture that he keeps with him or in his mind, or very possibly both, the image of his lover. Here we have to concede that, as Edmondson and Wells among others would be quick to point out, we don't know who this lover is, nor do we even know from these words alone that it is a man. But nothing so far has given us good reason to suppose that Shakespeare has suddenly switched his clearly very profound affections to someone else and irrespective of whether the sonnet sits in the sequence where it was originally published, or whether it belongs much earlier in the series, there is no evidence that points to this person being anyone other than the young man of whom we know Shakespeare is deeply enamoured.

- The poet and his lover are away from each other, with either the lover or the poet being "so far from home." The Quarto Edition prints these lines without any punctuation that could clarify who is away from home:

Is it thy spirit that thou send'st from thee

So farre from home into my deeds to prye,

and the majority of editors appear to retain this practice, even though it is tempting to structure the sentence:

Is it thy spirit that thou sendst from thee,

So far from home, into my deeds to pry,

which would then let the addressee be the person who is away 'from home', but this now would be pure conjecture, which is what we want to refrain from at this point.

- The poet wonders whether his lover is jealous and in any way possessive of him and the tone of voice with which he realises that that isn't the case is unambiguously disappointed:

O no, thy love, though much, is not so great.

It is my love that keeps mine eye awake,

Mine own true love that doth my rest defeat

This contrasting between the young man's love, which is 'much' but not as great as to stretch to this level of concern for his poet and the poet's love which 'true' is striking and telling and genuinely revealing as it is in keeping, entirely, with the profile we have so far been forming of the young man. It is good and valid grist to the mill that grinds the flour from which in time we may bake our bread, that is the loaf of evidence we seek to nourish our hunger for a plausible identity of the lover.

- The poet watches out for the young man while he, the young man does "wake elsewhere | From me far off, with others all too near."

And this 'all too near' is something we can confidently take both literally and metaphorically. We don't know who these others are, but we know for certain that as far as our poet is concerned, they are 'all too near' his lover. This can only mean that the lover is conducting relations with them that to William Shakespeare are upsetting, inappropriate, altogether too intimate for his liking. Which again tallies absolutely with what we have learnt about the young man's behaviour in Sonnets 33, 34, 35, 40, 41, 42, 48, and indeed 57 & 58.

This latter pair, 57 & 58, which in the collection comes only a couple of sonnets before this one, is particularly interesting in view of Shakespeare's use of the word 'tenure' here, which we've already briefly discussed earlier:

The scope and tenure of thy jealousy?

Because time and again, but most pointedly so far in Sonnets 57 & 58, do we get a sense that the addressee of these sonnets has some sort of title or even 'possession' over the poet.

Whether this is purely an emotional form of imbalance or one that is reflected in the two men's social status, or one that is in any way formalised in the relationship between them continues to be subject to speculation, but many times now we have come to conclude that Shakespeare must be talking to and about someone who is socially his superior.

If – and this is a big question that neither this sonnet nor any of the ones we have seen so far can answer – there is to the relationship also a component of patronage, then this sense acquires a genuine factuality. Colin Burrow in the Oxford Shakespeare edition of the Sonnets defines 'tenure' as "property that falls within the jurisdiction of a governor," without, unusually, giving the source, which may therefore mean that this is his own wording, but the Oxford English Dictionary does offer as its meaning numbered 3b, "(Title to) authority over or control of a person or thing," and if we permit the sense of 'property' to flow into our reading of the sonnet here then this shifts the dial towards a frequency on which we receive strong signals of a lord and patron who not only possesses our poet's heart in a poetic fashion but who actually has a degree of 'jurisdiction' or at the very least some sort of say over the poet. And when we look – as we will be doing ere long – more closely again at the possible potential candidates for said young man, then this nugget of 'information' will come to have additional bearing.

One thing we can say for certain from reading and hearing this sonnet alone is that whomever it is that William Shakespeare is writing and talking to, they are not only nowhere near him geographically at this moment, but also, and this is of much greater concern to him, nowhere near as committed to and concerned about him and therefore as truly and truthfully in love with him as he is to, about, and with them. And that, seeing it isn't exactly news to us by now, is then perhaps not so much a revelation as a fairly solid confirmation of what we have gleaned about Shakespeare's young lover before.

Always and forever bearing in mind that we can say nothing about these sonnets with any certainty and that virtually everything about them is conjecture, except the words, this is a particularly apt point in the proceedings to focus on what the words themselves tell us and simply add any insights we may gain from them to our 'depository', so to speak, of evidence, long before attempting to reach any kind of conclusion.

What the words unequivocally and really beyond any doubt convey to us is that:

- The poet is experiencing sleepless nights because he is seeing, either in a physical picture that he keeps with him or in his mind, or very possibly both, the image of his lover. Here we have to concede that, as Edmondson and Wells among others would be quick to point out, we don't know who this lover is, nor do we even know from these words alone that it is a man. But nothing so far has given us good reason to suppose that Shakespeare has suddenly switched his clearly very profound affections to someone else and irrespective of whether the sonnet sits in the sequence where it was originally published, or whether it belongs much earlier in the series, there is no evidence that points to this person being anyone other than the young man of whom we know Shakespeare is deeply enamoured.

- The poet and his lover are away from each other, with either the lover or the poet being "so far from home." The Quarto Edition prints these lines without any punctuation that could clarify who is away from home:

Is it thy spirit that thou send'st from thee

So farre from home into my deeds to prye,

and the majority of editors appear to retain this practice, even though it is tempting to structure the sentence:

Is it thy spirit that thou sendst from thee,

So far from home, into my deeds to pry,

which would then let the addressee be the person who is away 'from home', but this now would be pure conjecture, which is what we want to refrain from at this point.

- The poet wonders whether his lover is jealous and in any way possessive of him and the tone of voice with which he realises that that isn't the case is unambiguously disappointed:

O no, thy love, though much, is not so great.

It is my love that keeps mine eye awake,

Mine own true love that doth my rest defeat

This contrasting between the young man's love, which is 'much' but not as great as to stretch to this level of concern for his poet and the poet's love which 'true' is striking and telling and genuinely revealing as it is in keeping, entirely, with the profile we have so far been forming of the young man. It is good and valid grist to the mill that grinds the flour from which in time we may bake our bread, that is the loaf of evidence we seek to nourish our hunger for a plausible identity of the lover.

- The poet watches out for the young man while he, the young man does "wake elsewhere | From me far off, with others all too near."

And this 'all too near' is something we can confidently take both literally and metaphorically. We don't know who these others are, but we know for certain that as far as our poet is concerned, they are 'all too near' his lover. This can only mean that the lover is conducting relations with them that to William Shakespeare are upsetting, inappropriate, altogether too intimate for his liking. Which again tallies absolutely with what we have learnt about the young man's behaviour in Sonnets 33, 34, 35, 40, 41, 42, 48, and indeed 57 & 58.

This latter pair, 57 & 58, which in the collection comes only a couple of sonnets before this one, is particularly interesting in view of Shakespeare's use of the word 'tenure' here, which we've already briefly discussed earlier:

The scope and tenure of thy jealousy?

Because time and again, but most pointedly so far in Sonnets 57 & 58, do we get a sense that the addressee of these sonnets has some sort of title or even 'possession' over the poet.

Whether this is purely an emotional form of imbalance or one that is reflected in the two men's social status, or one that is in any way formalised in the relationship between them continues to be subject to speculation, but many times now we have come to conclude that Shakespeare must be talking to and about someone who is socially his superior.

If – and this is a big question that neither this sonnet nor any of the ones we have seen so far can answer – there is to the relationship also a component of patronage, then this sense acquires a genuine factuality. Colin Burrow in the Oxford Shakespeare edition of the Sonnets defines 'tenure' as "property that falls within the jurisdiction of a governor," without, unusually, giving the source, which may therefore mean that this is his own wording, but the Oxford English Dictionary does offer as its meaning numbered 3b, "(Title to) authority over or control of a person or thing," and if we permit the sense of 'property' to flow into our reading of the sonnet here then this shifts the dial towards a frequency on which we receive strong signals of a lord and patron who not only possesses our poet's heart in a poetic fashion but who actually has a degree of 'jurisdiction' or at the very least some sort of say over the poet. And when we look – as we will be doing ere long – more closely again at the possible potential candidates for said young man, then this nugget of 'information' will come to have additional bearing.

One thing we can say for certain from reading and hearing this sonnet alone is that whomever it is that William Shakespeare is writing and talking to, they are not only nowhere near him geographically at this moment, but also, and this is of much greater concern to him, nowhere near as committed to and concerned about him and therefore as truly and truthfully in love with him as he is to, about, and with them. And that, seeing it isn't exactly news to us by now, is then perhaps not so much a revelation as a fairly solid confirmation of what we have gleaned about Shakespeare's young lover before.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!