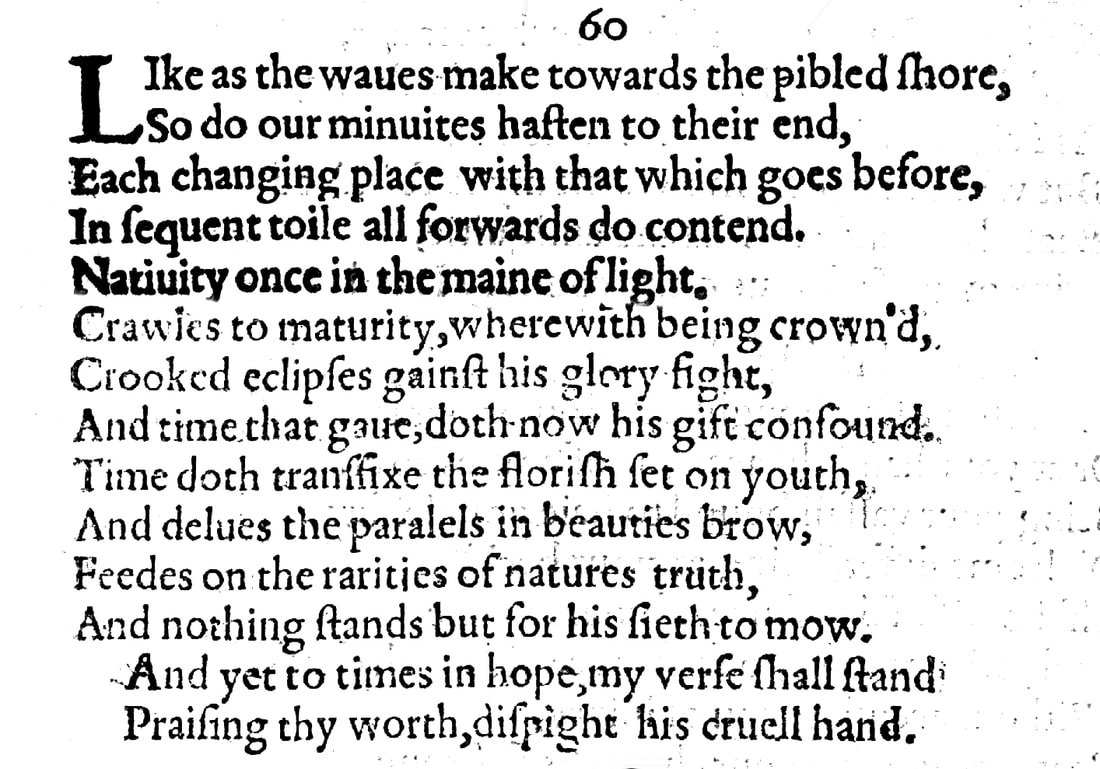

Sonnet 60: Like as the Waves Make Towards the Pebbled Shore

|

Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end: Each changing place with that which goes before, In sequent toil all forwards do contend. Nativity, once in the main of light, Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crowned, Crooked eclipses gainst his glory fight, And time that gave doth now his gift confound. Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth And delves the parallels in beauty's brow, Feeds on the rarities of nature's truth, And nothing stands, but for his scythe to mow. And yet to times in hope my verse shall stand, Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand. |

|

Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end: |

Much as the waves of the ocean continually race towards the pebbled shore, so the minutes of our lives never cease to rush towards their end, our death:...

The verb 'make' to mean 'move' here implies both an intent and a degree of urgency: 'make haste', 'he made for the train', 'can we make it?' |

|

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend. |

Each minute follows the one that went before it and in doing so takes its place, and thus they labour in a continuous sequence that can only ever go forward.

The notion that the minutes, much as the waves they have just been compared to, line up in a 'sequent toil' – 'toil' being continuous hard work – brings into the equation an effort beyond that of a natural occurrence, which is underlined by the the verb 'contend', which means 'to struggle' on the one hand, but also 'to compete'. And this latter meaning of competing with each other to get to the end – in the case of minutes – or to the shore – in the case of waves – sooner, if it were possible before the previous one, is particularly gratifying, because waves do look as if they were trying to take over each other, and anyone who has reached the reasonably to be hoped for estimated midpoint of their life will know how the minutes seem to more and more race each other to the ever larger looming finishing line... |

|

Nativity, once in the main of light,

Crawls to maturity |

The newborn human being, once having left the darkness of the womb and entered into the wide open ocean of light that is life, crawls towards being fully grown and mature...

'Main' really means 'ocean' but it is clearly used here metaphorically to mean the wide expanse of light. 'Nativity' as we are still mostly familiar with from the context of Christmas, simply means "the occasion of a persons's birth" (Oxford Languages) and this here stands for the person that has been born in general. 'Crawl' is of course what babies do until they can walk, and allowing this slow form of motion to describe our growing into our full adulthood does now invoke a contrasting slow passing of time, which is borne out by our experience: when we are children and very young adults, the world is our oyster and a year lasts us a long time. As a ten-year old, a year is a tenth of our lifetime and may just feel like that too. As a 30-year old, that same year now only makes up a 30th or just over 3% of our lifetime till then. By 50 it is a 50th or 2%. No wonder it can go by virtually unnoticed. And this acceleration only ever gets worse... |

|

wherewith being crowned

Crooked eclipses gainst his glory fight, |

And no sooner have we reached maturity than the decline sets in and adversity starts to fight the glorious perfection of being a young person in full possession of our powers.

'Crooked eclipses' is interpreted by different editors in slightly different ways. 'Crooked' here meaning 'malign', most point towards the ominous portents that an eclipse of the sun would have been understood as bearing and to the darkness that envelops the earth during an eclipse of the sun or, for that matter, on a moonless night. There is also a more figurative reading: often the Moon is partially eclipsed by the Earth, giving it a bent or 'crooked' sickle shape: the shape that the upright human body gradually acquires when age forces the spine to curve and our gait becomes bent, thus also fighting against or taking away from the splendour of a strong human form that can take life in their upright stride. Worth bearing in mind here again as on several previous occasions is that age advanced quickly on the Elizabethans, and the effects of exposure to the elements, physical exertion, and of having very limited ways to look after the body, visibly and early on took their toll. |

|

And time that gave doth now his gift confound.

|

And time itself, which early on, at the beginning of life, offers itself as the greatest gift when it spreads out before us, does now, as we get older, defeat or overthrow, or, by extension, take away that gift.

Shakespeare is fairly fond of the word 'confound'. As early as Sonnet 5 he says: For never-resting time leads Summer on To hideous winter and confounds him there where personified time obliterates summer by taking him – summer – to hideous winter. In Sonnet 8 it is the young man who "confounds | In singleness the parts" that he should bear, and following this sonnet here, over the next nine sonnets alone, Shakespeare will use 'confound' three more times. |

|

Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth

And delves the parallels in beauty's brow, |

Time pierces the glorious heyday that comes with youth and carves lines into the beautiful face of youth.

There are exactly one hundred instances of the word 'flourish' in Shakespeare's Complete Works, the vast majority of which in its musical meaning of a fanfare to announce the arrival of an important character or the beginning of a scene in the stage directions. Several times he uses it as the verb we are familiar with, 'to bloom' or 'blossom', but rarely as a noun to mean, as it does here, "an impressive and successful act or period" (Oxford Languages). Youth – in Shakespeare's day even more perhaps than today, when technology and healthcare allow us to 'flourish' right into our eighties or nineties under the right circumstances – is highly prized and directly and strongly associated with a person's achievements and term of agency. Your average Elizabethan of note really had about ten to twenty years, between about the age of 18 and their late forties to make their mark, if they were lucky. 'Transfix' here means "pierce with a sharp implement or weapon" rather than, as we now would mostly understand "cause (someone) to become motionless with horror, wonder, or astonishment." (Oxford Languages) And the idea of 'brow' standing in for 'forehead' or 'face' more generally is also one we have come across before. In Sonnet 2, Shakespeare warns: When forty winters shall besiege thy brow And dig deep trenches in thy beauty's field Thy youth's proud livery, so gazed on now Will be a tattered weed, of small worth held. In Sonnet 19, he admonishes time: O carve not with thy hours my love's fair brow, Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen And in Sonnet 33 he reminisces: Even so my sun one early morn did shine With all triumphant splendour on my brow In each case 'brow' is the face. |

|

Feeds on the rarities of natures' truth,

|

Time – which in Sonnet 19 was given the epithet 'devouring', after all, consumes the rare and therefore valuable attributes that come with nature's authentic qualities, such as genuine natural beauty...

Shakespeare uses 'truth' in different contexts to mean slightly different things, which all, however, can be encompassed in its principal definition: "the quality or state of being true" (Oxford Languages), be that now faithful, honest, sincere, genuine, unadulterated, or indeed factual. He has – as we know from many sonnets that have already appeared and as we will see confirmed shortly in particularly two sonnets just around the corner – an abject dislike of artifice when it comes to beauty, and so here 'nature's truth' is almost beyond doubt a reference to natural beauty that requires no artifice. It is the only kind of beauty Shakespeare respects, and it is one that he elsewhere ascribes most particularly and explicitly to his young man. It is also, of course, the beauty that is by definition most susceptible to the destructive force of time. |

|

And nothing stands, but for his scythe to mow.

|

...and there is nothing in this world that either literally or metaphorically stands up that will not ultimately be mowed down and brought to fall by time itself.

The scythe here belongs to time, of course, and we have encountered it before, in Sonnet 12: And nothing gainst Time's scythe can make defence Save breed to brave him, when he takes thee hence. |

|

And yet to times in hope my verse shall stand,

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand. |

And yet, having said all that, my verse shall stand up to time and, so is the hope, in times to come shall still be standing, to praise your worth despite the cruel hand of time which would seek to cut this down too. In other words: my verse – once more – shall overcome time.

And thus far this certainly holds true, otherwise we would not be discussing this sonnet. Interestingly, this is the only instance in the entire sonnet that either the young man or his worth are mentioned, and so this brief reference to "praising thy worth" is in fact the only praising of his worth this sonnet does, though it is fair to concede that as part of the large collection, series, or indeed sequence of sonnets we have seen and heard so far, this poet's verse more generally most certainly is doing its job of praising the young man's very great worth. |

For his quiet mediation on time in Sonnet 60, William Shakespeare once more borrows more or less directly from Ovid's Metamorphoses, a text we know he knew well and that influenced him greatly in the translation of his contemporary Arthur Golding. Its calm philosophical acceptance of mortality notwithstanding, it nevertheless infuses its reflective tone with an underlying anxiety about the drive towards finality that is inherent in our existence, and only just about manages to end on a concluding couplet that once more expresses Shakespeare's hope – as it is in this instance, rather than, as on previous occasions, unquestionable certainty – that his verse will be able to withstand the destructive force of decay that comes with the passing of time.

The last time Shakespeare so obviously and directly borrowed from Ovid was in Sonnet 55, where we also recognised a strong resemblance to Horace. As we noted at the time and again just a moment ago, Shakespeare's whole style is indebted to Arthur Golding whose translation of Ovid he clearly had access to and used extensively for inspiration.

Here is the passage editors commonly refer to in Metamorphoses (Book 15, lines 178-186; in Golding lines 197-207):

In all the world there is not that that standeth at a stay:

Things ebb and flow, and every shape is made to pass away.

The time itself continually is fleeting like a brook,

For neither brook nor lightsome time can tarry still. But look

As every wave drives other forth, and that that comes behind

Both thrusteth and is thrust itself, even so the times by kind

Do fly and follow both at once, and evermore renew.

For that that was before is left, and straight there doth ensue

Another that was never erst. Each twinkling of an eye

Doth change. We see that after day comes night and darks the sky,

And after night the lightsome Sun succedeth orderly.

The other thing that editors are quick to point out is that this sonnet, with its early mention of minutes and a possibly intended, possibly incidental, allusion to 'hour' with the choice of the word 'our' in the same line, sits at position 60, which happens to be the number of minutes in an hour, in what may or may not be an actual sequence of sonnets.

This question of sequentiality, as I have hinted at a number of times already, now becomes especially relevant, not least because of one particular scholar, Macdonald P Jackson, who, as I record this episode is aged 85 and Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. His work has strongly influenced and very directly guided a new edition of The Sonnets by two highly respected Shakespeare specialists in the UK, Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells, who have rearranged them in what they themselves call a 'putative chronological order' of composition, much in line with the approximate dating provided by Jackson.

This throws down something of a gauntlet to traditional scholarship which has for many centuries accepted the Quarto Edition as a more or less coherent sequence of sonnets that may well not be completely continuous and chronological, but that broadly makes sense in their division into essentially four parts:

- The Procreation Sequence 1–17

– The Fair Youth Sonnets beyond the Procreation Sequence: 18–126

– The 'Dark Lady' Sonnets: 127–152

– The two allegorical poems: 153 & 154

Edmondson and Wells leave the group consisting of Sonnets 1–60 intact, but then, following Jackson, start mixing things up, by placing Sonnets 61–77 just before this group, Sonnets 78–86 just after it, and then Sonnets 87–103 again before it. Significantly, they also advocate a reading of the sonnets that moves away from thinking of the subjects of these poems as principally one young man and one 'mysterious' woman, and also spread the remaining sonnets out over a longer period than many people have done so far.

Most fortunately, though, you do not have to make do with listening to me talk about their approach, because they very graciously have agreed to appear on Sonnetcast, and so our next episode will be our second Guest Special in which I will be talking to Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells themselves about their book All the Sonnets of Shakespeare, which, as far as we know for the first time, not only orders The Sonnets in this particular manner but also includes sonnets from Shakespeare's plays.

Interestingly, as you will hear in this conversation, Edmondson and Wells assume that the order of the Quarto Edition – which is the traditionally published order and the one we follow here in this podcast – was assembled and therefore numbered by William Shakespeare himself. And this is significant, because it implies that he at one point either consciously and deliberately or subconsciously and coincidentally allocated the number 60 to exactly the sonnet that talks about the minutes of our day.

And it is not the first time he does something similar. Sonnet 12 very memorably starts with the almost onomatopoeic line:

When I do count the clock that tells the time

which counting of course will yield a satisfying twelve hours. For someone like me who is learning the sonnets by heart, these connections between the poems and their numbers – be they intended or not – are especially helpful, because they serve as strong mnemonic hooks in the collection, and it is conceivable, but by no means certain and I am not even sure whether it is likely that this may have played a part in their ordering.

We noted with Sonnet 59 a change in tone from the previous sonnets, and this new, more reflective, philosophical, perhaps also more distanced tonality continues here into Sonnet 60 and, as it happens, beyond. Sonnet 61 will strongly feature the young lover who there once again is absent, thus reminding us of Sonnets 27 & 28 and also perhaps Sonnet 43; Sonnet 62 offers a profound and unflinching assessment of Shakespeare's own perception of himself in relation to the young man, before Sonnet 63 once again tries to stave off the inevitable, which is that the young man will one day, like Shakespeare, be past his prime and youthful beauty. With Sonnets 64 and 65, Shakespeare very much moves within the metaphorical territory here entered with Sonnet 60, by meditating on time, and then with Sonnet 66 we get a radical new momentum that flips quiet contemplation into frustration and rage.

Whether this means, by necessity, that therefore the sonnets that follow in the traditional series do in fact follow Sonnet 60 and those that went before in their order of composition after all, is not something we can answer here, nor possibly ever conclusively, but it is certainly worth keeping an eye out now for any clues that the words themselves may give us.

Certainly, these sonnets, Sonnet 60, 62, 63, 64, all show us a poet who is at a juncture in life where time matters to him. Where his age is causing him to examine his existence, where the beauty and youth of his lover are juxtaposed against his own appearance, that is "beated and chopped with tanned antiquity" in Sonnet 62 and "With Time's injurious hand crushed and oreworn" in Sonnet 63.

This would point towards a period in Shakespeare's life that not only allows but quite actively calls for such self-evaluation, and so it is satisfying to note that even the Jackson dating puts them between around 1594 and 1597, which is exactly when Shakespeare has just turned thirty. And that, as anyone who has ever turned thirty, or – which would be the approximate equivalent today – fifty is a milestone which makes most men and most likely many women too take stock and prompts us to pause and ponder the purpose and trajectory of our lives.

This, then, is the mood we find Shakespeare in now and it is one that is about to produce some quite astonishing, and astonishingly beautiful and powerful poetry, of an ilk we have not heard before.

The last time Shakespeare so obviously and directly borrowed from Ovid was in Sonnet 55, where we also recognised a strong resemblance to Horace. As we noted at the time and again just a moment ago, Shakespeare's whole style is indebted to Arthur Golding whose translation of Ovid he clearly had access to and used extensively for inspiration.

Here is the passage editors commonly refer to in Metamorphoses (Book 15, lines 178-186; in Golding lines 197-207):

In all the world there is not that that standeth at a stay:

Things ebb and flow, and every shape is made to pass away.

The time itself continually is fleeting like a brook,

For neither brook nor lightsome time can tarry still. But look

As every wave drives other forth, and that that comes behind

Both thrusteth and is thrust itself, even so the times by kind

Do fly and follow both at once, and evermore renew.

For that that was before is left, and straight there doth ensue

Another that was never erst. Each twinkling of an eye

Doth change. We see that after day comes night and darks the sky,

And after night the lightsome Sun succedeth orderly.

The other thing that editors are quick to point out is that this sonnet, with its early mention of minutes and a possibly intended, possibly incidental, allusion to 'hour' with the choice of the word 'our' in the same line, sits at position 60, which happens to be the number of minutes in an hour, in what may or may not be an actual sequence of sonnets.

This question of sequentiality, as I have hinted at a number of times already, now becomes especially relevant, not least because of one particular scholar, Macdonald P Jackson, who, as I record this episode is aged 85 and Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. His work has strongly influenced and very directly guided a new edition of The Sonnets by two highly respected Shakespeare specialists in the UK, Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells, who have rearranged them in what they themselves call a 'putative chronological order' of composition, much in line with the approximate dating provided by Jackson.

This throws down something of a gauntlet to traditional scholarship which has for many centuries accepted the Quarto Edition as a more or less coherent sequence of sonnets that may well not be completely continuous and chronological, but that broadly makes sense in their division into essentially four parts:

- The Procreation Sequence 1–17

– The Fair Youth Sonnets beyond the Procreation Sequence: 18–126

– The 'Dark Lady' Sonnets: 127–152

– The two allegorical poems: 153 & 154

Edmondson and Wells leave the group consisting of Sonnets 1–60 intact, but then, following Jackson, start mixing things up, by placing Sonnets 61–77 just before this group, Sonnets 78–86 just after it, and then Sonnets 87–103 again before it. Significantly, they also advocate a reading of the sonnets that moves away from thinking of the subjects of these poems as principally one young man and one 'mysterious' woman, and also spread the remaining sonnets out over a longer period than many people have done so far.

Most fortunately, though, you do not have to make do with listening to me talk about their approach, because they very graciously have agreed to appear on Sonnetcast, and so our next episode will be our second Guest Special in which I will be talking to Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells themselves about their book All the Sonnets of Shakespeare, which, as far as we know for the first time, not only orders The Sonnets in this particular manner but also includes sonnets from Shakespeare's plays.

Interestingly, as you will hear in this conversation, Edmondson and Wells assume that the order of the Quarto Edition – which is the traditionally published order and the one we follow here in this podcast – was assembled and therefore numbered by William Shakespeare himself. And this is significant, because it implies that he at one point either consciously and deliberately or subconsciously and coincidentally allocated the number 60 to exactly the sonnet that talks about the minutes of our day.

And it is not the first time he does something similar. Sonnet 12 very memorably starts with the almost onomatopoeic line:

When I do count the clock that tells the time

which counting of course will yield a satisfying twelve hours. For someone like me who is learning the sonnets by heart, these connections between the poems and their numbers – be they intended or not – are especially helpful, because they serve as strong mnemonic hooks in the collection, and it is conceivable, but by no means certain and I am not even sure whether it is likely that this may have played a part in their ordering.

We noted with Sonnet 59 a change in tone from the previous sonnets, and this new, more reflective, philosophical, perhaps also more distanced tonality continues here into Sonnet 60 and, as it happens, beyond. Sonnet 61 will strongly feature the young lover who there once again is absent, thus reminding us of Sonnets 27 & 28 and also perhaps Sonnet 43; Sonnet 62 offers a profound and unflinching assessment of Shakespeare's own perception of himself in relation to the young man, before Sonnet 63 once again tries to stave off the inevitable, which is that the young man will one day, like Shakespeare, be past his prime and youthful beauty. With Sonnets 64 and 65, Shakespeare very much moves within the metaphorical territory here entered with Sonnet 60, by meditating on time, and then with Sonnet 66 we get a radical new momentum that flips quiet contemplation into frustration and rage.

Whether this means, by necessity, that therefore the sonnets that follow in the traditional series do in fact follow Sonnet 60 and those that went before in their order of composition after all, is not something we can answer here, nor possibly ever conclusively, but it is certainly worth keeping an eye out now for any clues that the words themselves may give us.

Certainly, these sonnets, Sonnet 60, 62, 63, 64, all show us a poet who is at a juncture in life where time matters to him. Where his age is causing him to examine his existence, where the beauty and youth of his lover are juxtaposed against his own appearance, that is "beated and chopped with tanned antiquity" in Sonnet 62 and "With Time's injurious hand crushed and oreworn" in Sonnet 63.

This would point towards a period in Shakespeare's life that not only allows but quite actively calls for such self-evaluation, and so it is satisfying to note that even the Jackson dating puts them between around 1594 and 1597, which is exactly when Shakespeare has just turned thirty. And that, as anyone who has ever turned thirty, or – which would be the approximate equivalent today – fifty is a milestone which makes most men and most likely many women too take stock and prompts us to pause and ponder the purpose and trajectory of our lives.

This, then, is the mood we find Shakespeare in now and it is one that is about to produce some quite astonishing, and astonishingly beautiful and powerful poetry, of an ilk we have not heard before.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!