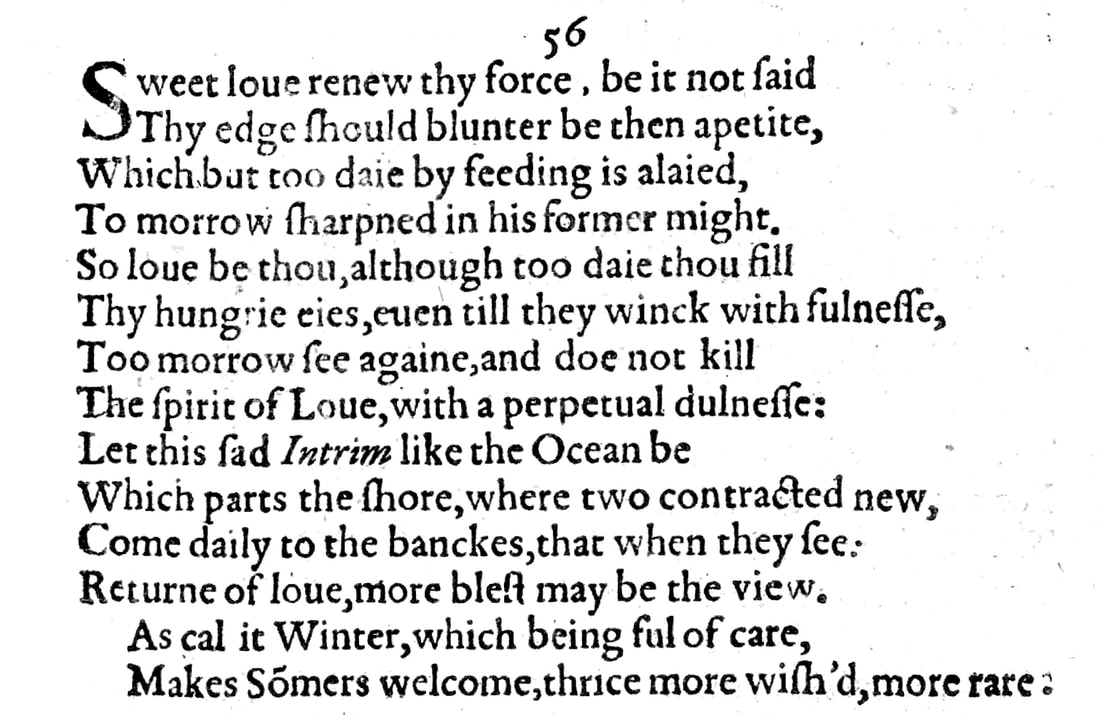

Sonnet 56: Sweet Love, Renew Thy Force, Be it Not Said

|

Sweet love, renew thy force, be it not said

Thy edge should blunter be than appetite, Which but today by feeding is allayed, Tomorrow sharpened in his former might. So, love, be thou: although today thou fill Thy hungry eyes, even till they wink with fullness, Tomorrow see again and do not kill The spirit of love with a perpetual dullness. Let this sad interim like the ocean be Which parts the shore, where two contracted new Come daily to the banks that when they see Return of love, more blessed may be the view; As call it winter, which, being full of care, Makes summer's welcome thrice more wished, more rare. |

|

Sweet love, renew thy force, be it not said

Thy edge should blunter be than appetite, |

Sweet love – addressed here is love itself, rather then the loved person – renew your force: let it not be said that you have an edge that is blunter than the edge of appetite...

The idea that love has an edge that gives it force when it is sharp is in itself quite original. It here appears to stem from the comparison to appetite of which we say that someone or something can whet, which means sharpen, it. The fact that appetite is brought into the equation may also be telling. Its first association – and the one here used as a metaphor – is of course food, but it also has obvious sexual connotations, and in many relationships sexual desire wanes long before the love or friendship fades. |

|

Which but today by feeding is allayed,

Tomorrow sharpened in his former might. |

...the appetite by eating something can be allayed or dampened or, to use Shakespeare's metaphor, blunted, but even if we do so today, tomorrow it will come back as sharp as it was before.

Also true is that the act of eating and therefore satisfying an appetite in turn also feeds it: while my hunger may subside for the moment today, tomorrow, I will want more of the same, especially if what I have eaten is something I like, something tasty. For our sense of language, there is a verb missing in the second line: we would expect something like 'tomorrow is sharpened', or 'tomorrow returns sharpened'. This here is taken as read. |

|

So, love, be thou: although today thou fill

Thy hungry eyes even till they wink with fullness |

You, love, be like appetite: even if today you fill your hungry eyes so much that they start to feel heavy and drowsy and in need of a nap...

'Even' here is pronounced as one syllable: e'en. |

|

Tomorrow see again and do not kill

The spirit of love with a perpetual dullness. |

...tomorrow look again at the lover or beloved person and so fill your hungry eyes again, and do not kill off the spirit of love with an everlasting dullness, meaning absence of hunger, desire, lust, or keen feeling of love. One of the dictionary definitions for 'dullness' is in fact "gloominess of mind or spirits: now especially as arising from want of interest," (Oxford Dictionaries) and it also means 'bluntness'.

'Spirit' here is pronounced as one syllable: sp'rit. |

|

Let this sad interim like the ocean be

Which parts the shore, where two contracted new Come daily to the banks that when they see Return of love, more blessed may be the view; |

Let us consider this sad period of separation that we are going through to be like an ocean which puts a large distance between the shores of two separate coastlines, and there, on these shores, two people who are newly betrothed to each other or engaged to be married daily come down to the beach – 'bank' here is the beach or the shore of the ocean, rather than the bank of a river – so that when they see the return of their loved one, they will be even happier, more blessed, more fortunate.

The idea, though – as on some previous occasions has been the case with our poet – it may not be strictly logical, is that a period of separation can be viewed like a large distance that is put between two lovers, and this distance, rather than making the lovers forget each other, keeps them running to the shore in eager anticipation of the lover's return, which would invariably be by boat or ship at the time, and could, under the right circumstances be seen from very far away. |

|

As call it winter, which, being full of care,

Makes summer's welcome thrice more wished, more rare. |

Or, much as we can look at this period of separation as an ocean, we may also call it a winter, which is a time of year that is cold, dark, full of heavy burdens and therefore cares, and because of this it makes the return of summer that much more keenly anticipated and desired.

This is reminiscent of Sonnet 52, where Shakespeare told the young man: Therefore are feasts so solemn and so rare Since seldom coming in the long year set Like stones of worth they thinly placed are, Or captain jewels in the carcanet. Here, similarly, the object of desire – the loved one, as indeed love itself – is compared to something that cannot always readily be had, but for which there is a season and this is partly what makes it so rare and desirable. We still use the proverb "absence makes the heart grow fonder," of course, which we briefly referenced also – and from a slightly different angle – in Sonnet 41 where the young man appears to have at least temporarily forgotten about, or certainly lapsed in, his love for William Shakespeare. |

Sonnet 56 is the second sonnet in the series so far in which William Shakespeare addresses not the young man, nor us as the general reader or listener about the young man, but an abstract concept, in this case love. The first instance when Shakespeare did something similar was Sonnet 19, which addressed itself to time. Here as then, this changes our perspective and lends the poem an emotional distance, which here is complemented by a direct reference to a hiatus in the relationship.

We do not know what causes "this sad interim" of which Shakespeare speaks, and there is virtually no way of finding out. It may be the case that this sonnet refers to the same prolonged period of separation of which we were aware between Sonnets 43 and 52, which would suggest that it has slipped out of its position in the sequence of composition, which is entirely possible. Similarly possible is that this is a new period of separation which has now commenced after the last one and following the reunion that appeared to be marked by Sonnets 52 and 53, for example because while Shakespeare is now back in town, his young lover has gone away for a time. Or it may simply be the case that although both Shakespeare and the young man are in London, they are either unable or unwilling to see each other, for whatever reason.

Sonnet 56 itself gives us no clue as to what is most likely, but Sonnets 57 & 58, which follow this sonnet and come as a particularly eye-catching pair, will do so, and I am here for once prepared to anticipate this a bit and foreshadow what we will learn shortly, which is that William Shakespeare simply doesn't know where his young lover is or what he is up to, and so to me it sounds plausible, so as not to claim it to be likely, that this sentiment is already being felt here and that therefore it is the young man who is either absent or out of reach.

On its own and in isolation, Sonnet 56 may at first glance seem like an innocuous little poem, but its almost slightly twee wistfulness belies a deeper crisis that is brewing in Shakespeare's relationship with his young man on the one hand, and in his own emotional and professional life on the other, and the two are of course in any case entwined and may well be far more closely enmeshed than we can know.

Every so often with a sonnet of Shakespeare's, the question it primarily poses is: why? Why is Shakespeare writing this, what brought this on? If you have a poet more or less out of the blue asking for love to renew itself and not to allow itself – over a period of absence or separation – to fade or lose its edge, then we are entitled to wonder: why would it? Aside from the obvious and banal answer that that's what relationships do over time if they are not nurtured – which is certainly true – the most obvious reason would be a specific sense the poet has that this particular relationship either is waning or in danger of doing so soon.

But of course: this does not come out of the blue. Bearing in mind always that we know little, and of what little we know we know almost nothing for certain, the impression we have been getting quite strongly and repeatedly is of a precarious relationship with an imperfect lover. From the very beginning it has been clear that Shakespeare is treading on a tightrope on which he has to reconcile an imbalance in age and status with his devotion and love for the young man. As early as Sonnet 24, we realised that this devotion is not commensurately reciprocated:

Yet eyes this cunning want to grace their art:

They draw but what they see, know not the heart.

Which suggests that Shakespeare simply does not know, at that time, what the young man is actually feeling towards him, when he himself has been telling the young man over several sonnets by now.

With Sonnet 25, Shakespeare thought he was on solid ground:

Then happy I that love and am beloved

Where I may not remove, nor be removed.

Only then to find himself backtracking furiously with Sonnet 26 and effectively apologising for having 'boasted' of his love. Sonnets 27 & 28, which come as a strongly tied pair, and Sonnets 29 and 30, which are at least thematically linked, all appeared to have been written when the two were away from each other, until Sonnet 31 signalled a renewed confidence and possibly a reunion, followed almost immediately by the big crisis that starts with Sonnet 33 and lasts intermittently until Sonnet 42. Sonnet 43 marks the beginning of the 'prolonged period of separation' we spoke of just a moment ago and many times before, whereby it is entirely possible – though I would consider it somewhat unlikely, given the tonality of these poems – that the period of separation that we recognise in Sonnets 27 through 30 and that which comes with Sonnets 43 through 51 are in fact the same trip or tour Shakespeare is on and that the whole interlude of despair over Shakespeare's young man getting off with Shakespeare's own mistress is carried out remotely, while they are away from each other.

What is clear is that by Sonnet 48, William Shakespeare worries about his young lover being stolen from him while he is away from him, and in Sonnet 49 he tells him that he is fully within his rights to leave him, since Shakespeare himself can't see any reason or cause why the young man should love him. With Sonnet 53 we had our extraordinary disparity between two possible 'messages' that the poem could carry, leaving us in categorical doubt as to whether Shakespeare is telling his lover that nobody is as constant, for which read faithful, as he, or the direct opposite, and with Sonnet 54 he offered his "beauteous and lovely youth" to distil his truth, which it turns out he has been doing in more ways than one, and not all of them ones that the young man is bound to find fulsomely flattering.

And so if Sonnet 56 now comes along and asks of love that it renew itself, this is really not all that surprising. Shakespeare is repeatedly put and extensively kept in limbo, and if you have ever been infatuated with someone who likes you and who enjoys being flattered and adored by you, but who will not ever meet you entirely at eye level and most certainly will not commit to you, then you will know exactly just what Shakespeare appears to be going through.

With its note of uncertainty and plea for love not to go stale, Sonnet 56 adds to the profile we are forming for Shakespeare's young lover and it sits perfectly with what we have come to understand about him so far. And because of this, it also further favours our reading of these sonnets up until now as standing in the context of one relationship with one young man, who at one point has an affair or a fling with a woman of whom we know only that Shakespeare considers her his love too and that she is therefore his mistress, since he is, of course, all the while married in Stratford-upon-Avon, which is something of which we can be absolutely certain.

There is of course the possibility – at least in theory – that Sonnet 56 is addressed to somebody completely different. It could, again in theory, even be addressed to Shakespeare's wife, but nobody seriously seems to submit the latter, which I too would consider exceptionally far-fetched, and for the former there are no real grounds to assume as much, since nothing about this sonnet or any of the ones that surround it suggests in any convincing manner that Shakespeare has diverted his affections from his young lover to somebody else.

And the two sonnets that now follow, Sonnet 57 & 58 give us, if not proof, since none such can be said to exist, then certainly even more compelling reason to believe that Shakespeare is in love with a fickle, independent-minded young man who lets him know in no uncertain terms what his place is in the world and who, in this relationship, owes what to whom...

We do not know what causes "this sad interim" of which Shakespeare speaks, and there is virtually no way of finding out. It may be the case that this sonnet refers to the same prolonged period of separation of which we were aware between Sonnets 43 and 52, which would suggest that it has slipped out of its position in the sequence of composition, which is entirely possible. Similarly possible is that this is a new period of separation which has now commenced after the last one and following the reunion that appeared to be marked by Sonnets 52 and 53, for example because while Shakespeare is now back in town, his young lover has gone away for a time. Or it may simply be the case that although both Shakespeare and the young man are in London, they are either unable or unwilling to see each other, for whatever reason.

Sonnet 56 itself gives us no clue as to what is most likely, but Sonnets 57 & 58, which follow this sonnet and come as a particularly eye-catching pair, will do so, and I am here for once prepared to anticipate this a bit and foreshadow what we will learn shortly, which is that William Shakespeare simply doesn't know where his young lover is or what he is up to, and so to me it sounds plausible, so as not to claim it to be likely, that this sentiment is already being felt here and that therefore it is the young man who is either absent or out of reach.

On its own and in isolation, Sonnet 56 may at first glance seem like an innocuous little poem, but its almost slightly twee wistfulness belies a deeper crisis that is brewing in Shakespeare's relationship with his young man on the one hand, and in his own emotional and professional life on the other, and the two are of course in any case entwined and may well be far more closely enmeshed than we can know.

Every so often with a sonnet of Shakespeare's, the question it primarily poses is: why? Why is Shakespeare writing this, what brought this on? If you have a poet more or less out of the blue asking for love to renew itself and not to allow itself – over a period of absence or separation – to fade or lose its edge, then we are entitled to wonder: why would it? Aside from the obvious and banal answer that that's what relationships do over time if they are not nurtured – which is certainly true – the most obvious reason would be a specific sense the poet has that this particular relationship either is waning or in danger of doing so soon.

But of course: this does not come out of the blue. Bearing in mind always that we know little, and of what little we know we know almost nothing for certain, the impression we have been getting quite strongly and repeatedly is of a precarious relationship with an imperfect lover. From the very beginning it has been clear that Shakespeare is treading on a tightrope on which he has to reconcile an imbalance in age and status with his devotion and love for the young man. As early as Sonnet 24, we realised that this devotion is not commensurately reciprocated:

Yet eyes this cunning want to grace their art:

They draw but what they see, know not the heart.

Which suggests that Shakespeare simply does not know, at that time, what the young man is actually feeling towards him, when he himself has been telling the young man over several sonnets by now.

With Sonnet 25, Shakespeare thought he was on solid ground:

Then happy I that love and am beloved

Where I may not remove, nor be removed.

Only then to find himself backtracking furiously with Sonnet 26 and effectively apologising for having 'boasted' of his love. Sonnets 27 & 28, which come as a strongly tied pair, and Sonnets 29 and 30, which are at least thematically linked, all appeared to have been written when the two were away from each other, until Sonnet 31 signalled a renewed confidence and possibly a reunion, followed almost immediately by the big crisis that starts with Sonnet 33 and lasts intermittently until Sonnet 42. Sonnet 43 marks the beginning of the 'prolonged period of separation' we spoke of just a moment ago and many times before, whereby it is entirely possible – though I would consider it somewhat unlikely, given the tonality of these poems – that the period of separation that we recognise in Sonnets 27 through 30 and that which comes with Sonnets 43 through 51 are in fact the same trip or tour Shakespeare is on and that the whole interlude of despair over Shakespeare's young man getting off with Shakespeare's own mistress is carried out remotely, while they are away from each other.

What is clear is that by Sonnet 48, William Shakespeare worries about his young lover being stolen from him while he is away from him, and in Sonnet 49 he tells him that he is fully within his rights to leave him, since Shakespeare himself can't see any reason or cause why the young man should love him. With Sonnet 53 we had our extraordinary disparity between two possible 'messages' that the poem could carry, leaving us in categorical doubt as to whether Shakespeare is telling his lover that nobody is as constant, for which read faithful, as he, or the direct opposite, and with Sonnet 54 he offered his "beauteous and lovely youth" to distil his truth, which it turns out he has been doing in more ways than one, and not all of them ones that the young man is bound to find fulsomely flattering.

And so if Sonnet 56 now comes along and asks of love that it renew itself, this is really not all that surprising. Shakespeare is repeatedly put and extensively kept in limbo, and if you have ever been infatuated with someone who likes you and who enjoys being flattered and adored by you, but who will not ever meet you entirely at eye level and most certainly will not commit to you, then you will know exactly just what Shakespeare appears to be going through.

With its note of uncertainty and plea for love not to go stale, Sonnet 56 adds to the profile we are forming for Shakespeare's young lover and it sits perfectly with what we have come to understand about him so far. And because of this, it also further favours our reading of these sonnets up until now as standing in the context of one relationship with one young man, who at one point has an affair or a fling with a woman of whom we know only that Shakespeare considers her his love too and that she is therefore his mistress, since he is, of course, all the while married in Stratford-upon-Avon, which is something of which we can be absolutely certain.

There is of course the possibility – at least in theory – that Sonnet 56 is addressed to somebody completely different. It could, again in theory, even be addressed to Shakespeare's wife, but nobody seriously seems to submit the latter, which I too would consider exceptionally far-fetched, and for the former there are no real grounds to assume as much, since nothing about this sonnet or any of the ones that surround it suggests in any convincing manner that Shakespeare has diverted his affections from his young lover to somebody else.

And the two sonnets that now follow, Sonnet 57 & 58 give us, if not proof, since none such can be said to exist, then certainly even more compelling reason to believe that Shakespeare is in love with a fickle, independent-minded young man who lets him know in no uncertain terms what his place is in the world and who, in this relationship, owes what to whom...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!