Sonnet 86: Was it the Proud Full Sail of His Great Verse

|

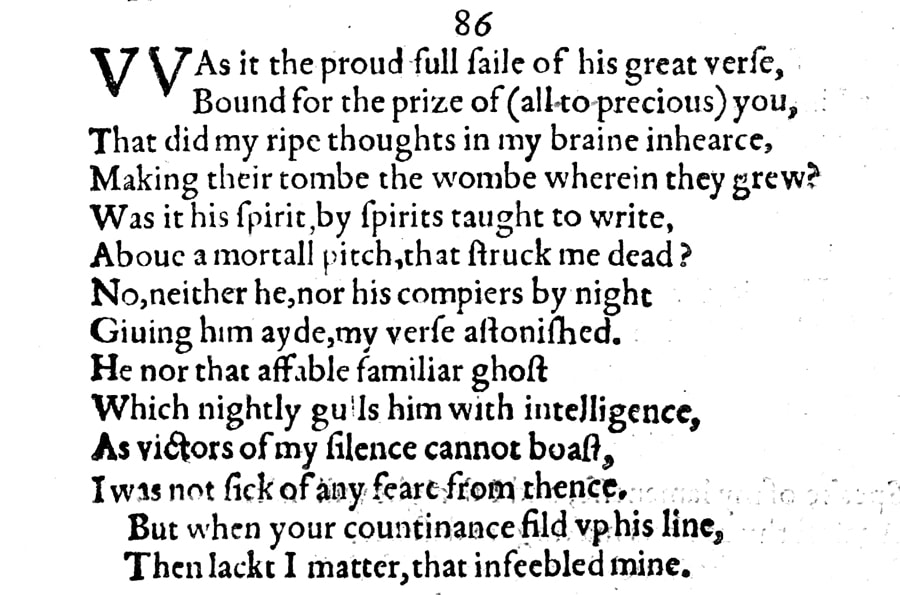

Was it the proud full sail of his great verse,

Bound for the prize of all-too-precious you That did my ripe thoughts in my brain inhearse, Making their tomb the womb wherein they grew? Was it his spirit, by spirits taught to write Above a mortal pitch that struck me dead? No, neither he nor his compeers by night, Giving him aid, my verse astonished. He, nor that affable familiar ghost, Which nightly gulls him with intelligence, As victors of my silence cannot boast: I was not sick of any fear from thence. But when your countenance filled up his line, Then lacked I matter, that enfeebled mine. |

|

Was it the proud full sail of his great verse,

Bound for the prize of all-too-precious you, |

Was it his – this other poet's – great verse which, like a majestic ship that sets out with full wind in its sails from its home harbour in proud splendour to go in search of some great treasure, is dedicated and therefore bound for you, who you are such a precious prize to win...

England, under Queen Elizabeth I, became a great seafaring nation but there was a fine line between privateering and piracy and so the imagery and symbolism employed here are multi-layered and, most likely deliberately ambiguous, indeed. |

|

That did my ripe thoughts in my brain inhearse,

Making their tomb the womb wherein they grew? |

...that buried my thoughts which were ripe and therefore just on the cusp of being plucked or born in my brain, thus turning the womb in which they had been growing into their own tomb, because they were never able to see the light of day?

We have previously seen Shakespeare associate thought with the heart, but here he puts forward the brain as the womb of thoughts, and it is worth noting that this is not the only time in the sonnets that he draws the connection between brain and thought. This just lest we gain or create the impression that for Shakespeare thought is always related to the heart. |

|

Was it his spirit, by spirits taught to write

Above a mortal pitch that struck me dead? |

Was it his – still this other poet's – inspired imagination, the 'vigour of his mind' as 'spirit' is also rendered sometimes, which in itself is taught by some supernatural spirits to write at a level which lies above that of a mere mortal which struck me dead with my poetry.

The suggestion being made by Shakespeare is that this other poet gets his inspiration and his ability to write 'above a mortal pitch' from the spirits or the souls of other, now deceased, writers, perhaps those long in the distant past, such as the great writers of antiquity, of ancient Greece and Rome, for example. Who these spirits might be is made no clearer here than who the rival poet is, but editors are abuzz with the possibility that there may lie a very specific clue here and in the next few lines, and we will of course get to discuss this in detail, but for the moment suffice it to say that the word 'spirits' here can have both benign and malign meanings, depending very much on whether they are being viewed in the Latin tradition as demons or in the Greek tradition as daemons: as evil or good spirits. And the first 'spirit' here is pronounced as one syllable, sp'rit, while the second 'spirits' are pronounced as two syllables. Editors like to point out that 'pitch' is a term used in falconry to mean "The height to which a falcon or other bird of prey soars before swooping down on its prey" (Oxford English Dictionary IV 16a) and this is certainly one of the many definitions we find, but to conclude from it that Shakespeare is particularly making reference to falconry is possibly somewhat far-fetched, because it also simply means "The highest or most extreme point, the top, the summit" (OED IV 15a), "The height to which anything rises" (OED IV 16b), and, here perhaps most obviously applicable "The highest point or degree of something; the acme, the climax." Noteworthy though is Shakespeare's escalation of the concept of being 'dumbstruck' or 'struck dumb' to being 'struck dead'. |

|

No, neither he, nor his compeers by night,

Giving him aid, my verse astonished. |

No, it was neither he himself nor his nocturnal aides or associates or fellows or comrades who assist him in his writing who stunned my verse and therefore me into silence.

'Compeers' may not be an entirely flattering term: it can have somewhat dismissive connotations, as in 'co-conspirators' or 'collaborators' in a negative sense. Using 'astonished' – here pronounced as four syllables, astonishèd – evokes a sense of being astounded, again dumbstruck, 'thunderstruck' via Old French from Latin extonare, 'out of thunder'. And so what is being conjured up is something that could amaze someone so much that they are effectively made speechless. |

|

He, nor that affable familiar ghost,

Which nightly gulls him with intelligence, |

Neither he, the poet himself nor that friendly attendant ghost who feeds or stuffs him nightly with information, or here perhaps more broadly inspiration...

'Affable' on its own is a positive term, which, apart from 'friendly' can also mean 'conversible' – easy to talk to, agreeable – whereas 'familiar' has a more complex crop of meanings. It suggests, much as we understand it today, something or someone that or who is known, perhaps even intimately so, but it also is used by Shakespeare and his contemporaries as a noun, sometimes together with 'spirit' as in a 'familiar spirit', which would come very close to 'familiar ghost' to mean a demon who attends a witch, and so this ghost, in Shakespeare's eyes may well be friendly and conversible, but that doesn't necessarily make him entirely 'legit', as we today might put it. 'Gulls' is yet another eye-catching and layered term. It means 'stuffs' or 'crams' or 'gorges', but it can also mean 'dupes', and so this 'intelligence' that helps the rival poet to write his poetry 'above a mortal pitch' may not be as wholesome and good as either he, the Rival Poet, or the young man think it is. |

|

As victors of my silence cannot boast:

I was not sick of any fear from thence. |

...all these cannot boast to be the 'victors of my silence', meaning the thing that effectively conquered me and made me fall silent: I was not sick with or from any fear that may have stemmed from them or their doing.

|

|

But when your countenance filled up his line,

Then lacked I matter, that enfeebled mine. |

But when your countenance, meaning on the one hand your face and more broadly your whole appearance, but also on the other hand your appearance of favour, your patronage, filled up his line, then I was left with nothing: I lacked all matter or substance, and it is this what enfeebled my line, making it go limp and weak and as a result silent.

And this final couplet is so laden with possible meanings and so suggestive on multiple levels, we need to examine it in quite a bit of detail... |

Sonnet 86 is the last of the Rival Poet group of sonnets, and it gives a final reason why William Shakespeare has, as he himself put it in Sonnet 85, become tongue-tied and been unable to express himself adequately in his praise of the young lover. Together with Sonnet 80 it bookends the group-within-a-group consisting of Sonnets 82 to 85 which together make an elaborate argument in Shakespeare's defence, and connecting, as it does, with the theme of seafaring and relaunching the metaphor of a sailing vessel, Sonnet 86 draws a direct link not only to the imagery of Sonnet 80, but also its tonality, which is decidedly distinct from that of the sonnets so bracketed. Both, this more suggestive tone and the thematic reference to Sonnet 80, as well as the on its own somewhat perplexing conclusion Sonnet 85 had come to, will help us greatly in our understanding of this heavily laden and layered poem.

And if you wonder why Sonnet 81 isn't mentioned there, that is because Sonnet 81 may or may not in fact belong with this sequence.

The first question you will hear discussed in the context of Sonnet 86, though, may well not be what it says about the relationship between Shakespeare and his young lover and between Shakespeare's young lover and this other poet, but about who this other poet might be.

The reason this question is most intensely examined in the context of Sonnet 86 is that Sonnet 86 may yield some usable clues. It suggests that this other poet – who here again is referred to in the specific singular rather than a generic plural – is receiving his inspiration from otherworldly sources, from "spirits" that teach him to write "above a mortal pitch," and speaks of "that affable, familiar ghost, which nightly gulls him with intelligence." And of course this absolutely prompts the entirely pertinent question: who might that be? Shakespeare moves from general 'spirits' that may well not be tied to an identifiable entity, such as imaginary ethereal forces that are capable of lending inspiration to a poet, to a particular 'ghost' who is characterised as both 'affable' and 'familiar', with affable, as we saw, being a generally friendly, amenable trait, whereas 'familiar' in Shakespeare's day can be something of a two-sided coin. Also, 'ghost', unlike 'spirit', in Shakespeare's use as in ours, would mostly imply the immortal soul of a once living person, such as the ghost of Hamlet's father, or Banquo's ghost in MacBeth, and so it is reasonable to assume here that Shakespeare is making reference not only to someone whom the reader of this poem would recognise, but through him point a clear arrow also at the rival poet, who would obviously be known to the young lover but who sadly is no longer known with any kind of certainty to us.

I will, of course, examine this question and pursue the various avenues that open up towards potential candidates for the Rival Poet, of whom one person especially is named often. But I won't do so here and now, because the Rival Poet surely deserves a special episode, dedicated entirely to him, and so I shall crave your indulgence and ask you to hold out until the next edition where all of what we think we can know about the Rival Poet shall be revealed.

This allows us to here concentrate on the underlying meaning of Sonnet 86, and while it is in the nature of things that the true meaning of a piece of poetry will invariably be tied to the person or people it purports to be written to or about, there are several observations we can make and, what is even more rewarding, conclusions we should then be able to draw.

Because what exactly is William Shakespeare here saying? He is saying that it was not the quality of this other man's poetry that made him tongue-tied, even though he would appear – or possibly claim – to be receiving his inspiration and assistance from an unworldly or otherworldly source. Instead, Shakespeare tells the young man:

But when your countenance filled up his line

Then lacked I matter, that enfeebled mine.

And many editors take this more or less at face value and faithfully translate and report: it was when the young man's appearance, or possibly, as we also considered, favour, became the substance of this rival's written line and therefore filled it up, then he, William Shakespeare, lacked this substance and therefore his line of verse became weak, by implication so weak as to fall silent. And we listen to this and we pause and we realise: this is ridiculous. It doesn't make sense:

I am your poet and your friend who loves you; I am your lover.

Somebody else starts writing poetry to and for you.

This makes me go tongue-tied.

But it isn't the great power of his verse that makes me go tongue-tied:

It is the fact that he is writing about you that does.

Why? If it isn't his poetry, then what is? Shakespeare is turning his group of sonnets into a circuitous argument that doesn't stack up. In Sonnet 80 he says:

O how I faint when I of you do write

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name

And in the praise thereof spends all his might

To make me tongue-tied, speaking of your fame.

And this would suggest that it is the fact that this is a 'better spirit', meaning a better poet, that makes me tongue-tied. That would make sense: if I have a lover whom I adore and much of our relationship is predicated on his admiring me for my writing and a better writer comes along, then that is obviously a problem. Here now in Sonnet 86, Shakespeare flatly contradicts this though and says, it isn't his great verse that killed off my ripe thoughts, it was when "your countenance filled up his line," which is the whole point of writing poetry to and for someone, that they should be the subject and therefore substance of your writing.

Now, we have noted before that logic is not William Shakespeare's strongest suit, and if this were all we have to go on, then we could quite conceivably leave it at that and say: well, as on several other occasions, the logic doesn't quite stack up, but we know what he's getting at: let it be so. Also, he's clearly upset, our Will, so maybe his thinking isn't entirely straight at the moment. And you're right: no it isn't. In more sense than one.

Because: you may recall what we noted when talking about Sonnet 85, which also threw us a bit of a curved ball. We wondered there, why good manners would forbid William Shakespeare to praise his young lover, why good manners would oblige him to keep his thoughts to himself, and one of the possible and more plausible answers to this question is: intimacy. What we today would call: sex. Manners in Shakespeare's day certainly require that you talk about sex in coded language, not openly, straightforwardly, directly.

You may also recall that when we were discussing Sonnet 80, we were struck by its sauciness, its suggestiveness, its highly charged, innuendo-laden language. We noted the highly unusual use of the phrase "Whilst he upon your soundless deep doth ride," and found it curious that while Shakespeare said of himself that he was a "worthless boat," in the metaphor of ships this other poet was, according to Will, "of tall building and of goodly pride." And we also remarked on the sharp change in tone, from rather overblown and borderline humorous, possibly also a bit sarcastic, to devastated and sincere, in the closing couplet of that sonnet:

Then if he thrive and I be cast away

The worst was this: my love was my decay.

And here William Shakespeare picks up on the imagery, even some of the tonality, but certainly the symbolism and several key components of vocabulary from Sonnet 80 and ties them directly to the argumentation that had been brought to an unnervingly unconvincing conclusion in Sonnet 85. What does this do?

It allows us and more than allows it invites us and more than invites it really rather forces us to see Sonnet 86 not in isolation, of course, but as the final and most revelatory complaint of this self-contained sequence. It takes us to the register of innuendo, of suggestiveness with its "proud, full sail' and with its reference to Sonnet 85 reminds us that there are certain things we simply cannot talk about directly, and then gives us an entirely valid answer to the question: what was it that really upset you so much, Will, that you couldn't write any more? Well, it was when your appearance, your presence, your favour, your attentions put lead into his pencil – not for writing purposes, but as a euphemism for 'got him going sexually', then I lacked the matter that would allow me to do the same. If we accept that Shakespeare not only loves his puns, but oftentimes needs them to be able to say what he has to say, so as to stay within the bounds of acceptable manners, then this line may well simply mean: look when you gave him an erection, I lost mine. In other words, it wasn't the fact that he wrote his fine poetry to you, that you took him as your poet, that destroyed me, what destroyed me was when I realised that you took him also as a lover.

Can we prove that this is what William Shakespeare means here? Of course not. So this is just conjecture? It is reading the words that are on the page in a way that actually makes sense. Could this be completely wrong? It could be wrong. Is that likely? Not very. Again, as once or twice before: think of William Shakespeare as a human being.

You are a writer and a poet and you are in love with this fabulous young man who has everything going for himself and who can be incredibly difficult to handle and demanding, but you have something extraordinary, genuinely special with him, and you really want this to continue because you can't bear to lose him, and a 'rival poet' pitches up. That's a nuisance, yes, especially if patronage, money, support, is involved, and that may well be the case, and we will look into this too when we look at who this rival may be. But if it's just about the poetry, then as a poet you can handle that. You can say, as Shakespeare does: look that's his style, he writes in this now fashionable, exuberant style, which I don't rate or share, I prefer to stick to a truthful language. You can argue this and you can make your case and you can then even say, but if you prefer his poetry, so be it: I am still your love. What though if you then betray me with him? And bearing in mind this wouldn't be the first time you do something like this. But on previous occasions, you have got off with my mistress: that was a weird and unnecessary thing to do, but I could rationalise that. You may or may not have had affairs and flings and encounters with other people when I wasn't around, that's even to some extent understandable, considering your age and your status. But to take on another poet, when you know that poetry is the essence of who I am, and make him your lover too? What do you expect me to say to that? That would wipe somebody out. Because no matter how good you are with your words: that's a punch to your guts that just completely knocks the wind out of you.

And what comes next is a sonnet that starts with the line

Farewell, thou art too dear for my possessing

And what follows after that is a whole series of sonnets that deal with a lover who has not just gone off the boil a bit or who has shown an interest in some other writer's writing. They deal with a lover who has betrayed you. And although there will be moments of tenderness again, and of adoration, of love and of a union that, once established, cannot really ever be entirely rent asunder, something here has been broken, and the scars of this will not entirely now go away.

And if you wonder why Sonnet 81 isn't mentioned there, that is because Sonnet 81 may or may not in fact belong with this sequence.

The first question you will hear discussed in the context of Sonnet 86, though, may well not be what it says about the relationship between Shakespeare and his young lover and between Shakespeare's young lover and this other poet, but about who this other poet might be.

The reason this question is most intensely examined in the context of Sonnet 86 is that Sonnet 86 may yield some usable clues. It suggests that this other poet – who here again is referred to in the specific singular rather than a generic plural – is receiving his inspiration from otherworldly sources, from "spirits" that teach him to write "above a mortal pitch," and speaks of "that affable, familiar ghost, which nightly gulls him with intelligence." And of course this absolutely prompts the entirely pertinent question: who might that be? Shakespeare moves from general 'spirits' that may well not be tied to an identifiable entity, such as imaginary ethereal forces that are capable of lending inspiration to a poet, to a particular 'ghost' who is characterised as both 'affable' and 'familiar', with affable, as we saw, being a generally friendly, amenable trait, whereas 'familiar' in Shakespeare's day can be something of a two-sided coin. Also, 'ghost', unlike 'spirit', in Shakespeare's use as in ours, would mostly imply the immortal soul of a once living person, such as the ghost of Hamlet's father, or Banquo's ghost in MacBeth, and so it is reasonable to assume here that Shakespeare is making reference not only to someone whom the reader of this poem would recognise, but through him point a clear arrow also at the rival poet, who would obviously be known to the young lover but who sadly is no longer known with any kind of certainty to us.

I will, of course, examine this question and pursue the various avenues that open up towards potential candidates for the Rival Poet, of whom one person especially is named often. But I won't do so here and now, because the Rival Poet surely deserves a special episode, dedicated entirely to him, and so I shall crave your indulgence and ask you to hold out until the next edition where all of what we think we can know about the Rival Poet shall be revealed.

This allows us to here concentrate on the underlying meaning of Sonnet 86, and while it is in the nature of things that the true meaning of a piece of poetry will invariably be tied to the person or people it purports to be written to or about, there are several observations we can make and, what is even more rewarding, conclusions we should then be able to draw.

Because what exactly is William Shakespeare here saying? He is saying that it was not the quality of this other man's poetry that made him tongue-tied, even though he would appear – or possibly claim – to be receiving his inspiration and assistance from an unworldly or otherworldly source. Instead, Shakespeare tells the young man:

But when your countenance filled up his line

Then lacked I matter, that enfeebled mine.

And many editors take this more or less at face value and faithfully translate and report: it was when the young man's appearance, or possibly, as we also considered, favour, became the substance of this rival's written line and therefore filled it up, then he, William Shakespeare, lacked this substance and therefore his line of verse became weak, by implication so weak as to fall silent. And we listen to this and we pause and we realise: this is ridiculous. It doesn't make sense:

I am your poet and your friend who loves you; I am your lover.

Somebody else starts writing poetry to and for you.

This makes me go tongue-tied.

But it isn't the great power of his verse that makes me go tongue-tied:

It is the fact that he is writing about you that does.

Why? If it isn't his poetry, then what is? Shakespeare is turning his group of sonnets into a circuitous argument that doesn't stack up. In Sonnet 80 he says:

O how I faint when I of you do write

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name

And in the praise thereof spends all his might

To make me tongue-tied, speaking of your fame.

And this would suggest that it is the fact that this is a 'better spirit', meaning a better poet, that makes me tongue-tied. That would make sense: if I have a lover whom I adore and much of our relationship is predicated on his admiring me for my writing and a better writer comes along, then that is obviously a problem. Here now in Sonnet 86, Shakespeare flatly contradicts this though and says, it isn't his great verse that killed off my ripe thoughts, it was when "your countenance filled up his line," which is the whole point of writing poetry to and for someone, that they should be the subject and therefore substance of your writing.

Now, we have noted before that logic is not William Shakespeare's strongest suit, and if this were all we have to go on, then we could quite conceivably leave it at that and say: well, as on several other occasions, the logic doesn't quite stack up, but we know what he's getting at: let it be so. Also, he's clearly upset, our Will, so maybe his thinking isn't entirely straight at the moment. And you're right: no it isn't. In more sense than one.

Because: you may recall what we noted when talking about Sonnet 85, which also threw us a bit of a curved ball. We wondered there, why good manners would forbid William Shakespeare to praise his young lover, why good manners would oblige him to keep his thoughts to himself, and one of the possible and more plausible answers to this question is: intimacy. What we today would call: sex. Manners in Shakespeare's day certainly require that you talk about sex in coded language, not openly, straightforwardly, directly.

You may also recall that when we were discussing Sonnet 80, we were struck by its sauciness, its suggestiveness, its highly charged, innuendo-laden language. We noted the highly unusual use of the phrase "Whilst he upon your soundless deep doth ride," and found it curious that while Shakespeare said of himself that he was a "worthless boat," in the metaphor of ships this other poet was, according to Will, "of tall building and of goodly pride." And we also remarked on the sharp change in tone, from rather overblown and borderline humorous, possibly also a bit sarcastic, to devastated and sincere, in the closing couplet of that sonnet:

Then if he thrive and I be cast away

The worst was this: my love was my decay.

And here William Shakespeare picks up on the imagery, even some of the tonality, but certainly the symbolism and several key components of vocabulary from Sonnet 80 and ties them directly to the argumentation that had been brought to an unnervingly unconvincing conclusion in Sonnet 85. What does this do?

It allows us and more than allows it invites us and more than invites it really rather forces us to see Sonnet 86 not in isolation, of course, but as the final and most revelatory complaint of this self-contained sequence. It takes us to the register of innuendo, of suggestiveness with its "proud, full sail' and with its reference to Sonnet 85 reminds us that there are certain things we simply cannot talk about directly, and then gives us an entirely valid answer to the question: what was it that really upset you so much, Will, that you couldn't write any more? Well, it was when your appearance, your presence, your favour, your attentions put lead into his pencil – not for writing purposes, but as a euphemism for 'got him going sexually', then I lacked the matter that would allow me to do the same. If we accept that Shakespeare not only loves his puns, but oftentimes needs them to be able to say what he has to say, so as to stay within the bounds of acceptable manners, then this line may well simply mean: look when you gave him an erection, I lost mine. In other words, it wasn't the fact that he wrote his fine poetry to you, that you took him as your poet, that destroyed me, what destroyed me was when I realised that you took him also as a lover.

Can we prove that this is what William Shakespeare means here? Of course not. So this is just conjecture? It is reading the words that are on the page in a way that actually makes sense. Could this be completely wrong? It could be wrong. Is that likely? Not very. Again, as once or twice before: think of William Shakespeare as a human being.

You are a writer and a poet and you are in love with this fabulous young man who has everything going for himself and who can be incredibly difficult to handle and demanding, but you have something extraordinary, genuinely special with him, and you really want this to continue because you can't bear to lose him, and a 'rival poet' pitches up. That's a nuisance, yes, especially if patronage, money, support, is involved, and that may well be the case, and we will look into this too when we look at who this rival may be. But if it's just about the poetry, then as a poet you can handle that. You can say, as Shakespeare does: look that's his style, he writes in this now fashionable, exuberant style, which I don't rate or share, I prefer to stick to a truthful language. You can argue this and you can make your case and you can then even say, but if you prefer his poetry, so be it: I am still your love. What though if you then betray me with him? And bearing in mind this wouldn't be the first time you do something like this. But on previous occasions, you have got off with my mistress: that was a weird and unnecessary thing to do, but I could rationalise that. You may or may not have had affairs and flings and encounters with other people when I wasn't around, that's even to some extent understandable, considering your age and your status. But to take on another poet, when you know that poetry is the essence of who I am, and make him your lover too? What do you expect me to say to that? That would wipe somebody out. Because no matter how good you are with your words: that's a punch to your guts that just completely knocks the wind out of you.

And what comes next is a sonnet that starts with the line

Farewell, thou art too dear for my possessing

And what follows after that is a whole series of sonnets that deal with a lover who has not just gone off the boil a bit or who has shown an interest in some other writer's writing. They deal with a lover who has betrayed you. And although there will be moments of tenderness again, and of adoration, of love and of a union that, once established, cannot really ever be entirely rent asunder, something here has been broken, and the scars of this will not entirely now go away.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!