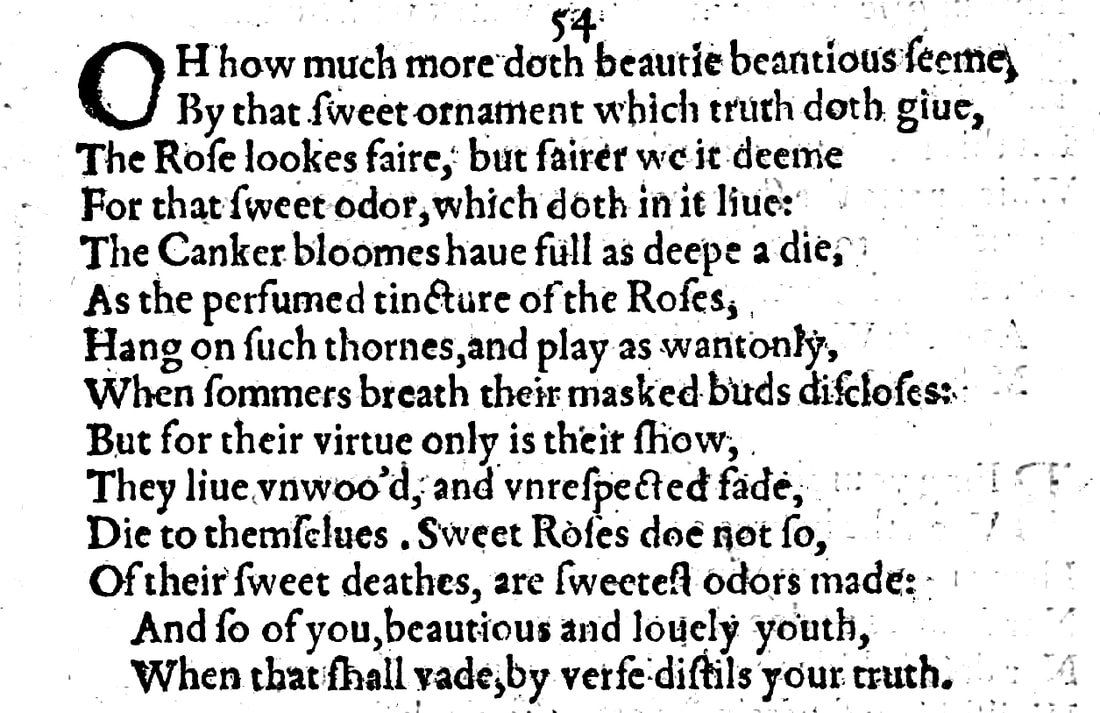

Sonnet 54: O How Much More Doth Beauty Beauteous Seem

|

O how much more doth beauty beauteous seem

By that sweet ornament which truth doth give: The rose looks fair, but fairer we it deem For that sweet odour which doth in it live. The canker blooms have full as deep a dye As the perfumed tincture of the roses, Hang on such thorns and play as wantonly When summer's breath their masked buds discloses, But for their virtue only is their show, They live unwooed and unrespected fade, Die to themselves; sweet roses do not so, Of their sweet deaths are sweetest odours made. And so of you, beauteous and lovely youth, When that shall vade, by verse distils your truth. |

|

O how much more doth beauty beauteous seem

By that sweet ornament which truth doth give: |

How much more does beauty appear beautiful to us if and when it is augmented by truth, for which here read truthfulness, as in faithfulness, as much as honesty or authenticity in a more general sense.

In other words: a beautiful thing to us appears a lot more beautiful if it is also genuine, or, applied to a person, a beautiful human being is even more beautiful if they are similarly authentic, true, genuine, and honest, and therefore, by extension, faithful. |

|

The rose looks fair, but fairer we it deem

For that sweet odour which doth in it live. |

And here comes an example with a metaphor attached to it: the rose looks beautiful, but we think of it or judge it even more beautiful because it has a sweet – which here as above really means lovely – smell.

'Odour' to us today has decidedly negative connotations: we associate it with 'body odour', and other bad smells. This is evidently not the case in Shakespeare's day, where the word quite to the contrary suggests a pleasant fragrance. And the notion that this 'sweet odour' lives in the rose is significant: the rose, in Shakespeare's understanding, does not just happen to have a nice smell, but the perfume is part of its essence that can, as he is about to explain, be distilled and is therefore able, in concentrated form, to live on. |

|

The canker blooms have full as deep a dye

As the perfumed tincture of the roses, |

The blossoms of the dog rose or wild rose have every bit as deep a colour as the perfumed dye of the rose...

This, we should note, was more the case in Shakespeare's day than it is today, because in Elizabethan England the rose had not yet been cultivated to the intensity of colour that it can have today, and so there was less of a differential between the wild rose and the rose than there is now. |

|

Hang on such thorns and play as wantonly

When summer's breath their masked buds discloses, |

...they hang on thorns – or, technically, thorny stems – just like roses, and they play in as unrestrained a way when the summer breeze uncovers their buds, which are otherwise masked by their petals.

'Wantonly' is an interesting choice of word here. It is the only time in the entire canon of his complete works that Shakespeare uses it, though there are 89 other occurrences of 'wanton' – both as an adjective and as a verb – 'wantonness', and 'wantons', with a whole range of subtly different meanings, though hardly ever the one we today associate with it of 'deliberate and unprovoked' in relation to 'a cruel or violent act', nor all that frequently in the overtly sexual context, meaning 'sexually unrestrained'. As a verb, it used to mean 'play' or 'frolic', and that is really what we should understand here, a frolicking way of playing in the air. |

|

But for their virtue only is their show,

|

But because their only virtue is their appearance...

The placing of 'for' here is unusual and at first glance tricky for us. It tempts us to read, 'but their show is only for their virtue', which doesn't make sense and which is not what this says. 'For' here means 'because'. |

|

They live unwooed and unrespected fade,

Die to themselves; |

...they, the canker blooms or wild roses, live without ever being desired or wanted by anyone and so they fade unrespected, which here has a double meaning of both, unregarded, meaning nobody has ever paid much attention to them, and also not respected, because they are of not much use to the world, and so as a result they die alone.

|

|

sweet roses do not so,

Of their sweet deaths are sweetest odours made. |

The same is not true for roses: when they die, then sweet – as in, again, lovely – fragrances are made of them, when they are being turned into perfume.

|

|

And so of you, beauteous and lovely youth,

When that shall vade, by verse distils your truth. |

And the same will happen to you, beautiful and lovely youth: when your beauty and your youth fades and disappears, then through the medium of verse your essence will be distilled and preserved for the world to enjoy in times to come.

Many editors emend 'by' to 'my', which also makes perfect sense, and which may in fact be correct, if 'by' is a misprint. But the line also works with 'by': in this case it is truth that distils itself through – by – verse; if we read 'my', instead, then the poet becomes much more prominent because then it is 'my', the poet's, verse that distils your truth. I am myself tempted to favour the second reading, because it more strongly echoes those sonnets we have already seen, but then also the next one in the series, Sonnet 55, which all position the poet, William Shakespeare, as the person who can make the young man live forever, as opposed, to, say, he himself producing children, which was the theme and indeed purpose of the entire Procreation Sequence, Sonnets 1-17. But my approach – I quite strongly believe – has to be to retain what we should assume to be Shakespeare's wording wherever it is at all possible and plausible, and unless there are strong indications that the wording we have is not Shakespeare's, but a typesetter's error, and since in this case the original is in fact more subtle and more elegant than the emendation, I have, along with several other editors, retained the Quarto Edition's 'by' here. And there is another aspect that I want to highlight: when you read these sonnets out loud or learn them by heart and recite them, then a very subtle but important difference in emphasis comes about through reading 'by' as opposed to 'my': with the emendation to 'my', the emphasis rests entirely on 'my verse', it is my verse that distils your truth. With the original wording, the emphasis is on 'distils', which even more strongly references the act of distillation which also features in Sonnets 5 & 6. And this, as will become clear and clearer, is truly significant to our understanding of how these sonnets do or do not hang together. |

After the turmoil of Sonnets 33 to 42 and the prolonged period of separation signalled by Sonnets 43 to 51, which in turn was followed by a joyous, sensual and tender reunion with Sonnets 52 and 53, Sonnet 54 assumes a more aloof, marginally moralistic tone which nevertheless manages to connect with, and in fact reference, sonnets that appeared much earlier in the series, specifically Sonnets 5 & 6, in which William Shakespeare encouraged the young man to distil his beauty by giving his essence to a woman and producing an heir, much as roses are distilled as perfume and thus live on long after their death.

Through the pair of Sonnets 15 & 16 and then also Sonnet 17, Shakespeare gradually abandoned the project of encouraging the young man to have children, and with Sonnet 18 he made it abundantly clear that it is his verse that can make the young man live forever. Sonnet 54 similarly suggests that it is the verse of a poet – by implication, or, if we were to accept the widely used emendation in the last line of 'by' to 'my' then by express identification this poet – which distils, here not the beauty of the young man, but his truth, meaning his inner value, his constancy. And with this it also connects almost directly to the sonnet that precedes it, which closes – as we saw – on an exquisitely ambiguous notion of the 'constant heart': we were unable to determine there whether Shakespeare meant to tell the young man that he is unparalleled not only for his beauty but also for his constancy or – what in view of recent events seemed more likely – that his beauty is unparalleled, but nobody can have him as a constant, faithful lover.

If our reading of the sonnets thus far has been more or less correct and Sonnet 53 does indeed put in question the young lover's constancy – for which read faithfulness, for which in turn again read truthfulness and therefore 'truth' – then Sonnet 54 makes sense not only as an isolated instance of Shakespeare pontificating borderline pompously about the virtue of truthfulness, but much more interestingly and meaningfully as a continuation of the concern touched on in the sonnet that immediately follows the reunion, Sonnet 53. And what, from a purely human perspective, could seem more natural? You are away from your lover for a while, you are reunited with him, you express the bliss and wonder of this reunion and also your unease or uncertainty about your lover's conduct and commitment to you – an unease and uncertainty for which, as we have established, there is good reason – and so you extol the virtue of constancy, commitment, truthfulness and offer to do for this the same as you have already done and said you have done for the young man's beauty: you offer to now also distil his truth, his essence, his very being, as well as the beauty you already have distilled and said you have distilled very early on in a sequence of events and sonnets that reflect those events.

What the sonnet also does – and for this we may be particularly grateful – is anchor the recipient as a beautiful young man:

And so of you, beauteous and lovely youth

When that shall vade, by verse distils your truth.

Since there is no way in which Shakespeare could address either an old person or a woman as 'beauteous and lovely youth', we know for certain that he is talking directly to a beautiful young man.

There are of course those who would argue that there is no evidence to suggest that Sonnet 54 is addressed to the same young man as Sonnet 53, or Sonnet 53 to the same person as Sonnets 33 to 42 or any of the other sonnets. But nothing so far has suggested that there are different characters involved in these sonnets, and much of what we have seen and heard by contrast suggests very strongly that the person whom all of these sonnets so far have been written to or about is exactly the same young man, and so since we do not have any other evidence either way, my inclination is and remains to maintain that in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend, and the strong likelihood that presents itself to us is that these sonnets so far form a more or less intact, coherent group that has been composed in the context of a relationship with one young man.

If we were to question whether this is the same beautiful young man as the one of any of the previous sonnets where we were certain that they were written to or about a beautiful young man, then we would have to ask ourselves: how many beautiful young men is Shakespeare in love with or cares enough about to compose sonnets for during the relatively short period in which he writes these particular sonnets. That it is a relatively short period during which he writes these particular sonnets also is not established with absolute certainty, but scholars and editors of very varying perceptions broadly agree that the entire group that encompasses Sonnets 1 to 60 must have been composed over a two to three year period some time between approximately 1593 and 1597.

Holding on to this thought will help us when we come to look more closely at the order of the sonnets and at their potential addressees or subjects, which, as we move towards Sonnet 60, will be quite soon.

What comes next though is a sonnet that categorically plants the poet once more as the provider of a durable monument to the young lover: in an echo of, possibly even homage to, Horace and Ovid, Shakespeare employs tropes of classical poetry to cement his own role as – if nothing else – the preserver of the young man's unsurpassed worth.

Through the pair of Sonnets 15 & 16 and then also Sonnet 17, Shakespeare gradually abandoned the project of encouraging the young man to have children, and with Sonnet 18 he made it abundantly clear that it is his verse that can make the young man live forever. Sonnet 54 similarly suggests that it is the verse of a poet – by implication, or, if we were to accept the widely used emendation in the last line of 'by' to 'my' then by express identification this poet – which distils, here not the beauty of the young man, but his truth, meaning his inner value, his constancy. And with this it also connects almost directly to the sonnet that precedes it, which closes – as we saw – on an exquisitely ambiguous notion of the 'constant heart': we were unable to determine there whether Shakespeare meant to tell the young man that he is unparalleled not only for his beauty but also for his constancy or – what in view of recent events seemed more likely – that his beauty is unparalleled, but nobody can have him as a constant, faithful lover.

If our reading of the sonnets thus far has been more or less correct and Sonnet 53 does indeed put in question the young lover's constancy – for which read faithfulness, for which in turn again read truthfulness and therefore 'truth' – then Sonnet 54 makes sense not only as an isolated instance of Shakespeare pontificating borderline pompously about the virtue of truthfulness, but much more interestingly and meaningfully as a continuation of the concern touched on in the sonnet that immediately follows the reunion, Sonnet 53. And what, from a purely human perspective, could seem more natural? You are away from your lover for a while, you are reunited with him, you express the bliss and wonder of this reunion and also your unease or uncertainty about your lover's conduct and commitment to you – an unease and uncertainty for which, as we have established, there is good reason – and so you extol the virtue of constancy, commitment, truthfulness and offer to do for this the same as you have already done and said you have done for the young man's beauty: you offer to now also distil his truth, his essence, his very being, as well as the beauty you already have distilled and said you have distilled very early on in a sequence of events and sonnets that reflect those events.

What the sonnet also does – and for this we may be particularly grateful – is anchor the recipient as a beautiful young man:

And so of you, beauteous and lovely youth

When that shall vade, by verse distils your truth.

Since there is no way in which Shakespeare could address either an old person or a woman as 'beauteous and lovely youth', we know for certain that he is talking directly to a beautiful young man.

There are of course those who would argue that there is no evidence to suggest that Sonnet 54 is addressed to the same young man as Sonnet 53, or Sonnet 53 to the same person as Sonnets 33 to 42 or any of the other sonnets. But nothing so far has suggested that there are different characters involved in these sonnets, and much of what we have seen and heard by contrast suggests very strongly that the person whom all of these sonnets so far have been written to or about is exactly the same young man, and so since we do not have any other evidence either way, my inclination is and remains to maintain that in the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend, and the strong likelihood that presents itself to us is that these sonnets so far form a more or less intact, coherent group that has been composed in the context of a relationship with one young man.

If we were to question whether this is the same beautiful young man as the one of any of the previous sonnets where we were certain that they were written to or about a beautiful young man, then we would have to ask ourselves: how many beautiful young men is Shakespeare in love with or cares enough about to compose sonnets for during the relatively short period in which he writes these particular sonnets. That it is a relatively short period during which he writes these particular sonnets also is not established with absolute certainty, but scholars and editors of very varying perceptions broadly agree that the entire group that encompasses Sonnets 1 to 60 must have been composed over a two to three year period some time between approximately 1593 and 1597.

Holding on to this thought will help us when we come to look more closely at the order of the sonnets and at their potential addressees or subjects, which, as we move towards Sonnet 60, will be quite soon.

What comes next though is a sonnet that categorically plants the poet once more as the provider of a durable monument to the young lover: in an echo of, possibly even homage to, Horace and Ovid, Shakespeare employs tropes of classical poetry to cement his own role as – if nothing else – the preserver of the young man's unsurpassed worth.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!