Sonnet 39: O How Thy Worth With Manners May I Sing

|

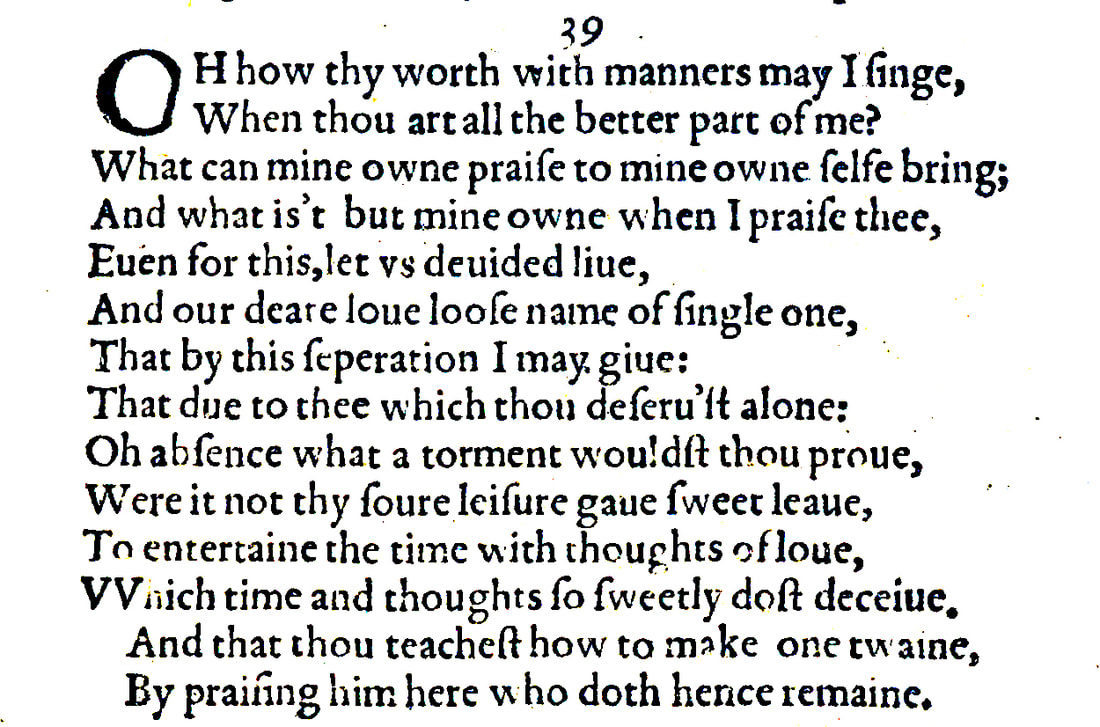

O how thy worth with manners may I sing,

When thou art all the better part of me? What can mine own praise to mine own self bring, And what is't but mine own when I praise thee? Even for this, let us divided live And our dear love lose name of single one, That by this separation I may give That due to thee which thou deservest alone. O absence, what a torment wouldst thou prove Were it not thy sour leisure gave sweet leave To entertain the time with thoughts of love, Which time and thoughts so sweetly dost deceive, And that thou teachest how to make one twain By praising him here who doth hence remain. |

|

O how thy worth with manners may I sing

When thou art all the better part of me? |

How may I sing your praises with good manners, when you are the best part of me?

Singing your own praises is bad manners – it becomes blowing your own trumpet – and so if you, my lover, are the best part of me then, as the next two lines explain: |

|

What can mine own praise to mine own self bring,

And what is't but mine own when I praise thee? |

What could I benefit from my own praise – in fact it would be positively damaging, because it is such bad manners – and yet what is it other than me praising myself if I praise you, because you are everything that is best in me.

The premise of this first quatrain is twofold: first, the classical notion that two lovers are as one because they are two halves of the same person and thus able to not only complement but actually complete each other; and, second, the proverbial notion that a friend is one's second self. |

|

Even for this, let us divided live

And our dear love lose name of single one, |

For this reason alone, or for exactly this reason, let us live apart and thus let our cherished love no longer be called – as it would be, in a classical sense – the love of two people who are as one.

Colin Burrow points out that 'divided' here as elsewhere in Shakespeare is not a neutral term but has strong negative connotations, much as we today still would consider a 'divided nation' not simply one that is simply split into two parts, but is so for adverse reasons. This appears to directly reference Sonnet 36 which similarly suggested that "we two must be twain | Although our undivided loves are one." But the reason given here for such a separation is quite different. Whereas there it was so that I alone could bear the burden of a damaged reputation from whatever it was that has happened, here it is: |

|

That by this separation I may give

That due to thee which thou deservest alone. |

So that, because of this separation, I am then free to give you that which you alone deserve, namely your praise. Because if we are separate then logically I am then no longer praising myself if I praise you.

The assumption is that a physical separation will count as also an emotional separation, even though that is not, of course, really sought. |

|

O absence, what a torment wouldst thou prove

|

Oh, absence what a torment you would prove to be...

|

|

Were it not thy sour leisure gave sweet leave

To entertain the time with thoughts of love |

...if it weren't for the fact that the sour – here meaning bitter and therefore by implication unpleasant, even painful – leisure that you impose on me by keeping me away from my love provided me with the sweet – and therefore by implication lovely and enjoyable – permission and also opportunity to pass this time with thoughts of love...

|

|

Which time and thoughts so sweetly dost deceive.

|

...both of which – time and the thoughts of love – you, absence, sweetly, for which again read pleasantly and enjoyably, beguile.

'Beguile' means to "charm or enchant (someone), often in a deceptive way" (Oxford Languages), and here this sense of deception is brought forward by the verb 'deceive' standing in for 'beguile'. It is of course an act of self-deception to wallow in thoughts of love for someone who is in fact absent, but so strongly connected to Sonnet 36 and the group that precedes it, and in light of the two sonnets that are just about to come, this may also allude to the kind of deception an absent lover may be tempted to while being away. |

|

And that thou teachest how to make one twain

By praising him here who doth hence remain. |

And – this is another reason why you, absence, are not the torment you would otherwise be – for the fact that you teach me how I can make the one union that we are as lovers be two people purely by the act of praising the half who is not here with me, namely him, the young man.

The idea is that by praising him, who is actually physically absent, I can bring him back to me, because I thus have him in my thoughts: we are therefore both together and apart at the same time. A similar notion of being present-absent will be explored again soon in Sonnets 43 and 44. |

Sonnet 39 is the last of four sonnets that seem to disrupt the sequence of events until Sonnet 35, and picks up more or less directly with Sonnet 36 by suggesting that it would be best if William Shakespeare were separate from the young man, though for wholly different reasons. The sonnet appears to post-rationalise an imposed absence of, or from, the young man, while also echoing the question posed by Sonnet 38 of how to sing the young man's praises, but then again developing this into a totally different direction. As with Sonnets 36, 37, and 38, it is not entirely clear whether this sonnet has been grouped together with these other poems here simply because it appears to make reference to at least two of them, or whether it really does belong into this smaller group, irrespective of whether that smaller group is in the right place or not.

Sonnet 39 is not especially problematic, but nor does it immediately strike us as wholly compelling. The argument that is being made for our understanding is one that doesn't take us very much further, other than perhaps in that it offers some additional nuance to the insights we have so far gained into the relationship between William Shakespeare and his young man.

The desire, so as not to say need, that Shakespeare has to praise the young man is taken for granted and is used to put a positive spin on what appears to be an otherwise externally imposed separation. Like Sonnet 36, it speaks essentially from a rhetorician's point of view who ought to be able to coach anything and everything in a reasonable sounding argument, even if strictly speaking it isn't: in this sense it comes close to being sophistic. Shakespeare is hardly seriously suggesting that he and his young lover should be separated just so that he, Shakespeare can sing his, the young man's, praises. Infinitely more plausible is that the separation, much as the need to praise the young man for his by now well-established and oft-cited worth, is a given: we now have to make the most of both, and since my role, as the poet, the rhetorician, and the – in oh so many ways - needier party in the constellation, is to shower you with praise, let me take this pre-existing requirement as the perfect reason why the separation we have to endure is in fact a good thing.

What is telling about the sonnet is that – whether it was composed around the same time as Sonnet 36, and the imposed absence or separation therefore stems, as Sonnet 36 strongly suggests, from an external scandal or perceived damage or threat to the young man's and therefore Shakespeare's reputation, or whether it was composed during some other time of separation and has slipped in here because it seems so closely related to 36, it is fairly emphatic in one particular regard: you are the best part of me. Our dear love has the name of being a 'single one', meaning that we two are one. And this would seem to point towards a balance of probabilities possibly tipping slightly in favour of this sonnet being in fact unconnected to the upheavals encountered from Sonnet 33 onwards, and that what look like references to us, such as the similarities in lines like

Sonnet 36:

Let me confess that we two must be twain

Although our undivided loves are one

Sonnet 39:

Even for this, let us divided live

And our dear love lose name of single one

are in fact a coincidence. We cannot know this, let alone know this for certain. But the only potentially negative note that could tentatively be interpreted as a suggestion that anything the young man has done was not right attaches itself very slightly to line 12:

Which time and thoughts so sweetly dost deceive.

And there only because 'deceive' is a word that has obviously and categorically dishonest connotations for us, as it did for Shakespeare, but quite possibly for Shakespeare in this context much less than for us. If he really wants 'deceive' to mean 'beguile' here and any deception, such as it is, referred to relates not to the young man but to the fact that absence in this way can proverbially make the heart grow fonder by deceiving me into believing I have my lover near me through praising him, when in fact he is far away from me, then Sonnet 39 can really be read and understood mostly at face value as an attempt by the poet to make his time away from his lover more bearable by exercising his craft to rationalise that what he wishes were not the case – his lover's absence – is in fact a good thing.

Sonnet 39 takes us to the end of this brief detour and excursion into different poetic territory, and with our next sonnet, Sonnet 40, we will be right back, bang in the middle again of the tempestuous bad weather that started with Sonnet 33, and we will learn substantially more and clearer details about what exactly has been going on, over the next three Sonnets 40, 41, and 42...

Sonnet 39 is not especially problematic, but nor does it immediately strike us as wholly compelling. The argument that is being made for our understanding is one that doesn't take us very much further, other than perhaps in that it offers some additional nuance to the insights we have so far gained into the relationship between William Shakespeare and his young man.

The desire, so as not to say need, that Shakespeare has to praise the young man is taken for granted and is used to put a positive spin on what appears to be an otherwise externally imposed separation. Like Sonnet 36, it speaks essentially from a rhetorician's point of view who ought to be able to coach anything and everything in a reasonable sounding argument, even if strictly speaking it isn't: in this sense it comes close to being sophistic. Shakespeare is hardly seriously suggesting that he and his young lover should be separated just so that he, Shakespeare can sing his, the young man's, praises. Infinitely more plausible is that the separation, much as the need to praise the young man for his by now well-established and oft-cited worth, is a given: we now have to make the most of both, and since my role, as the poet, the rhetorician, and the – in oh so many ways - needier party in the constellation, is to shower you with praise, let me take this pre-existing requirement as the perfect reason why the separation we have to endure is in fact a good thing.

What is telling about the sonnet is that – whether it was composed around the same time as Sonnet 36, and the imposed absence or separation therefore stems, as Sonnet 36 strongly suggests, from an external scandal or perceived damage or threat to the young man's and therefore Shakespeare's reputation, or whether it was composed during some other time of separation and has slipped in here because it seems so closely related to 36, it is fairly emphatic in one particular regard: you are the best part of me. Our dear love has the name of being a 'single one', meaning that we two are one. And this would seem to point towards a balance of probabilities possibly tipping slightly in favour of this sonnet being in fact unconnected to the upheavals encountered from Sonnet 33 onwards, and that what look like references to us, such as the similarities in lines like

Sonnet 36:

Let me confess that we two must be twain

Although our undivided loves are one

Sonnet 39:

Even for this, let us divided live

And our dear love lose name of single one

are in fact a coincidence. We cannot know this, let alone know this for certain. But the only potentially negative note that could tentatively be interpreted as a suggestion that anything the young man has done was not right attaches itself very slightly to line 12:

Which time and thoughts so sweetly dost deceive.

And there only because 'deceive' is a word that has obviously and categorically dishonest connotations for us, as it did for Shakespeare, but quite possibly for Shakespeare in this context much less than for us. If he really wants 'deceive' to mean 'beguile' here and any deception, such as it is, referred to relates not to the young man but to the fact that absence in this way can proverbially make the heart grow fonder by deceiving me into believing I have my lover near me through praising him, when in fact he is far away from me, then Sonnet 39 can really be read and understood mostly at face value as an attempt by the poet to make his time away from his lover more bearable by exercising his craft to rationalise that what he wishes were not the case – his lover's absence – is in fact a good thing.

Sonnet 39 takes us to the end of this brief detour and excursion into different poetic territory, and with our next sonnet, Sonnet 40, we will be right back, bang in the middle again of the tempestuous bad weather that started with Sonnet 33, and we will learn substantially more and clearer details about what exactly has been going on, over the next three Sonnets 40, 41, and 42...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!