Sonnet 55: Not Marble, Nor the Gilded Monuments

|

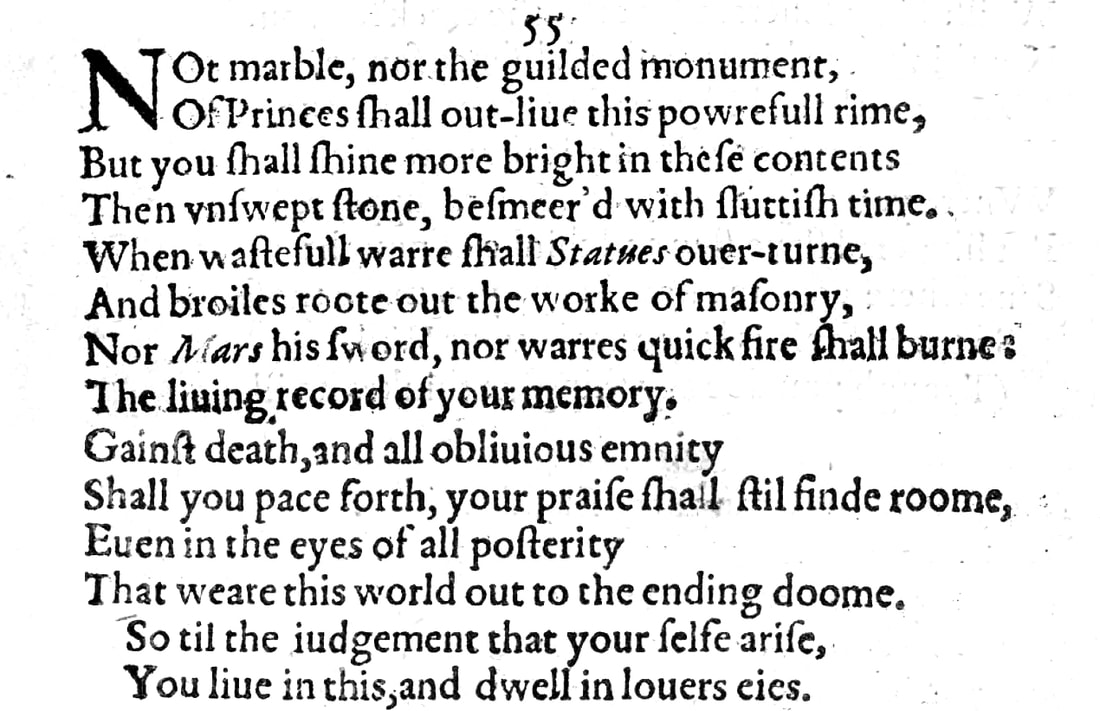

Not marble, nor the gilded monuments

Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme, But you shall shine more bright in these contents Than unswept stone, besmeared with sluttish time. When wasteful war shall statues overturn And broils root out the work of masonry, Nor Mars his sword, nor war's quick fire shall burn The living record of your memory. Gainst death and all oblivious enmity Shall you pace forth, your praise shall still find room, Even in the eyes of all posterity That wear this world out to the ending doom. So till the judgement that yourself arise You live in this and dwell in lovers' eyes. |

|

Not marble, nor the gilded monuments

Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme, |

Neither memorials made of marble, such as are often found on the tombs of wealthy people, or such as are erected for those considered great and good and powerful, nor the gilded monuments that are set up to honour kings and princes shall last longer than this powerful piece of poetry that I am writing right here and now...

The idea – and it is certainly not a new one, but one which poets right into antiquity have entertained, as we shall see – is that even the most durable materials cannot withstand the ravages of time, whereas words that people remember or continue to read will last, as Shakespeare himself put it in his Sonnet 18, "so long as men can breathe or eyes can see," meaning for as long as human civilisation exists. |

|

But you shall shine more bright in these contents

Than unswept stone, besmeared with sluttish time. |

...but you shall live on and shine more brightly in the contents of this rhyme, meaning in these lines that I am writing for you just now, than the unswept stone of a tomb, for example, which over time gets grubby and illegible and therefore loses all meaning.

The fact that the stone here described is 'unswept' tells us that it is uncared for, effectively forgotten: nobody after a while bothers to clean and tend it, and so it gets 'besmeared' with time, meaning that time leaves its ugly traces on it. Both 'besmeared' and 'sluttish' have strong moral, even sexual, connotations. The main meaning of 'sluttish' in Shakespeare's day is 'slovenly', or, of a person, as Oxford Dictionaries defines it, "having low standards of cleanliness," but even at the time it also serves as a derogatory term to describe a woman who is "sexually promiscuous or provocative." And there is a subtle difference in two possible readings of 'with'. If we understand that the unswept stone over time gets besmeared with all manner of things – soot, dust, dirt, grime – then the 'sluttish' describes time generally as 'slovenly' or indeed 'promiscuous' because it applies itself carelessly and indiscriminately to everything. If we read the line as the stone being besmeared with time itself, then time is a thing and of things 'sluttish' can also simply mean 'unclean, dirty, grimy, untidy'. As so often with Shakespeare, he may well be aware of the double layering and be applying it here deliberately. Similarly, we can either understand the line as saying that you – the addressee of this poem, who, as far as we can tell, is still the young man – will shine more brightly in these lines than you will shine in the unswept stone of a memorial or grave, or simply that you will shine more brightly in these lines than the unswept stone itself will be able to do. Both are possible and both make sense. |

|

When wasteful war shall statues overturn

|

When, or while, over time wars – which are by definition wasteful because they are destructive and cause both human and material damage and loss – overturn statues, such as the ones of mighty kings or leaders...

This happens to this day, both as collateral, incidental damage and as deliberate acts of re-appropriation. One of the most enduring images of the Iraq war in 2003, for example, is of people tearing down a statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad. |

|

And broils root out the work of masonry,

|

...and tumults or skirmishes or civil wars root out – meaning overturn or destroy – the monuments, memorials, even palaces and fortifications that have been built by masons...

|

|

Nor Mars his sword, nor war's quick fire shall burn

The living record of your memory. |

...when all of this has happened or while all of this is happening, neither the sword of Mars which, Mars being the god of war, is a powerful symbol of destruction, nor the ravaging, fast-consuming fire of war itself shall be able to burn and therefore destroy the living record of your memory.

A record implies a written document, which here clearly is this sonnet, and we know from experience, not least of the Great Fire of London, how vulnerable paper records is to catastrophe, but the fact that Shakespeare uses 'the' rather than a specific 'this' suggests that he is referring to a larger set, such as the collection of these sonnets in their entirety, or a number of sonnets he has already written. The difference matters, because it supports our notion of these sonnets – or at any rate many of these sonnets – together forming one record which is addressed to and about and composed in the context of the relationship with, so far, one young man. |

|

Gainst death and all oblivious enmity

|

Against the force of death – which ultimately conquers us all – and all the other adverse forces that cause us to fall into oblivion and thus be forgotten, such as war, decay, time...

|

|

Shall you pace forth, your praise shall still find room

Even in the eyes of all posterity That wear this world out to the ending doom. |

...you shall step forward and in doing so prove that you are alive and take your place in the world with the confidence of a hero: your praise which I here compose, and therefore your exalted reputation generally shall always find room and therefore always be admitted; and it shall do so in the eyes – for which read the opinion as well as the literal ability of eyes to see and read – into all posterity, meaning for as long as there is anyone alive who can assume any consciousness of our erstwhile existence, and this posterity, these civilisations that follow us will last until doomsday, which in the biblical tradition is Judgement Day.

Interesting is the notion that it is the eyes of a posterity 'that wear this world out to the ending doom', and it suggests both, a posterity that, no matter what, keeps going until the end of the world, but also, of course, a posterity that through its very existence uses the world and ultimately exhausts it. And note that 'even' is pronounced with one syllable here: e'en. |

|

So till the judgement that yourself arise

You live in this and dwell in lovers' eyes. |

And so, until Judgement Day when you – like all dead – will arise and meet your Maker, you live in this poem and in doing so you continue to reside and therefore also live in the eyes of lovers, which here has three possible meanings that are likely intentional, or at least two of them are:

- Firstly, you live in the eyes of lovers generally, because lovers pass their time and soothe their souls by reading love poetry: this has ever been and ever will be thus. – Secondly, you live in your lovers' eyes, which here may be meant as a plural or indeed as a singular. The Quarto Edition has louers which leaves this open. But Shakespeare elsewhere is highly conscious of the age difference between himself and the young man and also more than once muses on what the young man should do if and when – as would be the expectation considering this age difference – the young man survives him, so if we are assuming that this poem is addressed to the young man whom we have so far fairly firmly established in our minds, then this particular reading of lover's in the singular referring to Shakespeare himself is unlikely, and the reading of the young man's lovers in the plural also has its limitations, because they will all die long before any meaningful 'posterity' comes about. - Thirdly, the people who in future generations read these lines will by default turn into admirers and therefore 'lovers' of you, because you live in this poetry and your presence is so strong and compelling that even long after your death readers will simply adore you. This turns out to be only partly true: we certainly still think of and imagine and speculate as to the identity of the addressee, and so he absolutely lives on, but unlike our reaction to Sonnet 18 Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer's Day, where we knew almost nothing about the young man, by now the picture we are getting of Shakespeare's lover is not one of unimpeachable adorableness, and so, perhaps ironically, Shakespeare's poetry, has succeeded in keeping his man alive, but it also shows us his considerable character flaws, which only, of course, serves to make him more human and therefore much more interesting. |

With the supremely confident Sonnet 55, William Shakespeare returns to a theme he has handled similarly deftly before: the power of poetry itself to make the young man live forever. In a departure from previous instances, he here appears to borrow directly from Horace and Ovid, who are both Roman poets of the turn into the first millennium of the Common Era, striking a therefore more generic note, but unlike these classical precedents for verses that can outlast the supposedly durable substances of physical structures, he employs his poem once again not to celebrate himself but to praise his young lover.

The most famous exponent of this idea that it is Shakespeare's own poetry that will bestow immortality on the young man is the celebrated Sonnet 18 Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer's Day, but in fact it started to find its way into the poems as early as Sonnet 15, and then was present throughout Sonnets 17, 18, and 19. In Sonnet 23, Shakespeare took a somewhat different angle and told his young lover that he should "learn to read what silent love hath writ," because "To hear with eyes belongs to love's fine wit," and in doing so contrasted his own tendency to get tongue-tied with his ability to express himself in writing.

In Sonnet 32, Shakespeare mildly, and, we felt at the time, possibly mildly ironically, disparaged his own writing and suggested it would easily and naturally be surpassed, or, as he put it "outstripped by every pen," but that his young lover should keep the sonnets for the love he bore him, even if he could not possibly do so for their literary merit.

Then, with Sonnets 38 and 39, Shakespeare questioned on the one hand how he or anyone could not be inspired by the young man to write poetry and demanded that anyone who would do so "bring forth eternal numbers to outlive long date," and on the other hand how his, Shakespeare's, praise of the young man in his poetry could achieve anything other than immodestly praising himself, since the young man is after all simply the best part of his lover, William Shakespeare.

Of these two sonnets we wondered whether in fact they belonged exactly where they are found, although they very clearly appear to be part of this larger group of Sonnets 1 to 60 and so most likely are not vastly out of place, And similarly with Sonnet 55, since it stands out quite so singularly in mood and style from the ones that surround it, we are allowed to ask ourselves whether it was written at around the same time, and indeed this particular question of when these sonnets were written in relation to each other, and to what extent we can think of any of them as 'a sequence' or parts of chronologically sequential writings will very soon become of great importance and interest to us, which we will therefore discuss in much greater detail when we come to the end of this more or less coherent group formed by Sonnets 1 to 60.

Since I mentioned Horace and Ovid at the beginning, I should take this opportunity to point to the passages in Horace and Ovid that prompt scholars to believe Shakespeare was inspired by them, and it is easy to see how they come to this conclusion:

Horace, in his Odes, writes, here in the translation by James Michie in the Penguin Classics edition:

More durable than bronze, higher than Pharaoh's

Pyramids is the monument I have made,

A shape that angry wind or hungry rain

Cannot demolish, nor the innumerable

Ranks of the years that march in centuries.

I shall not wholly die: some part of me

Will cheat the goddess of death, for while High Priest

And Vestal climb our Capitol in a hush,

My reputation shall keep green and growing.

Arthur Golding, who was a contemporary of Shakespeare's, although a generation older, wrote a seminal translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses, and we know with great certainty that Shakespeare knew this book and used it extensively for inspiration, because he frequently references it and in some cases borrows near verbatim quotations. There we find:

Now have I brought a work to end which neither Jove's fierce wrath,

Nor sword, nor fire, nor fretting age with all the force it hath

Are able to abolish quite. Let come that fatal hour

Which (saving of this brittle flesh) hath over me no power,

And at his pleasure make an end of mine uncertain time.

Yet shall the better part of me assured be to climb

Aloft above the starry sky. And all the world shall never

Be able for to quench my name. For look how far so ever

The Roman Empire by the right of conquest shall extend,

So far shall all folk read this work. And time without all end

(If poets as by prophecy about the truth may aim)

My life shall everlastingly be lengthened still by fame.

Fascinating about this latter passage is that, short though it be, it contains several turns of phrase that have a familiar ring to us from Shakespeare, even beyond Sonnet 55: "the better part of me," "all the world," "time without all end" all sound decidedly Shakespearean to us, because they were clearly currency then, and Golding's Ovid very obviously helped form Shakespeare's style.

One more observation should be made that is pertinent not only to this Sonnet 55, but in fact to all the sonnets since what I have referred to and like to think of as the 'reunion' that followed an obvious period of separation. From Sonnet 52 onwards, Shakespeare has been addressing his young man as 'you' again.

'Again' here is an operative term: there is a school of thought which holds that the fact alone that Shakespeare addresses some of these poems to their recipient with the familiar 'thou' and some with the more formal 'you' is 'proof' that they must be different individuals. This does not stand up to scrutiny for long though because even within the sequence that makes up the Procreation Sonnets, 1-17, which really are so specific in their intent and so consistent in their characterisation of the addressee that the vast majority of scholars and editors accept they appear to be written to and for the same young man, Shakespeare switches from 'thou' to 'you' several times. There we noted that this seems to be happening on occasions when it would help the poet to acknowledge or signal the stark difference in status between him and the young man, who to all intents and purposes sounds like he is a young nobleman or certainly a person of high social standing. And most tellingly, in Sonnet 24, as the only sonnet in the collection, Shakespeare uses both forms of address, 'you' and 'thou', in the same poem. Sonnet 24 is one we identified as 'complex and quietly insightful', as it reflects the great complexity of Shakespeare's relationship with his young man.

We cannot possibly, therefore, conclude from the fact that Shakespeare sometimes uses 'you' and sometimes 'thou' that he is therefore talking to different people: he clearly uses both forms of address for the same person. That settled, we can then begin to examine what, if any, meaning there is to this group of sonnets, 52 to 58, using the more formal form of address, 'you'. Of course we don't know for certain. But if we latch on once more to this notion of the form of address being a subtle pointer to an awareness of status, then this here once again makes perfect sense.

Sonnet 52 is one we identified as the closest Shakespeare has come so far to answering the question whether or not the relationship between him and his young man is a sexual one. If that is the case, then doing so once again – as he has done before when entering potentially sensitive territory – with a sonnet that speaks to its recipient with a degree of formality and reverence is perhaps not so unwise. He then keeps this going for Sonnet 53, which either salutes the young man for his constancy or chastises him for his inconstancy, we can't possibly be sure which, and this constructive ambiguity again is a bold undertaking by a poet who may be skating on comparatively thin ice, considering the constellation he is in. In Sonnet 54 it is 'my', Shakespeare's, verse that distils 'your', the young man's, truth and therefore truthfulness and authenticity, and here with Sonnet 55 we are still firmly in the land of 'you'.

Sonnet 56 changes register once more completely and addresses not the young man but love itself, but with Sonnets 57 & 58 we are introduced to a whole new level of status awareness and very conscious highlighting of where you, my young man, are in relation to me, the poet, in this world.

Sonnet 55, then, is fascinating for all manner of reasons, but not least because it forms something of an apex on which pivots this whole relationship into a profoundly thought-provoking and in several aspects quite perturbing phase...

The most famous exponent of this idea that it is Shakespeare's own poetry that will bestow immortality on the young man is the celebrated Sonnet 18 Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer's Day, but in fact it started to find its way into the poems as early as Sonnet 15, and then was present throughout Sonnets 17, 18, and 19. In Sonnet 23, Shakespeare took a somewhat different angle and told his young lover that he should "learn to read what silent love hath writ," because "To hear with eyes belongs to love's fine wit," and in doing so contrasted his own tendency to get tongue-tied with his ability to express himself in writing.

In Sonnet 32, Shakespeare mildly, and, we felt at the time, possibly mildly ironically, disparaged his own writing and suggested it would easily and naturally be surpassed, or, as he put it "outstripped by every pen," but that his young lover should keep the sonnets for the love he bore him, even if he could not possibly do so for their literary merit.

Then, with Sonnets 38 and 39, Shakespeare questioned on the one hand how he or anyone could not be inspired by the young man to write poetry and demanded that anyone who would do so "bring forth eternal numbers to outlive long date," and on the other hand how his, Shakespeare's, praise of the young man in his poetry could achieve anything other than immodestly praising himself, since the young man is after all simply the best part of his lover, William Shakespeare.

Of these two sonnets we wondered whether in fact they belonged exactly where they are found, although they very clearly appear to be part of this larger group of Sonnets 1 to 60 and so most likely are not vastly out of place, And similarly with Sonnet 55, since it stands out quite so singularly in mood and style from the ones that surround it, we are allowed to ask ourselves whether it was written at around the same time, and indeed this particular question of when these sonnets were written in relation to each other, and to what extent we can think of any of them as 'a sequence' or parts of chronologically sequential writings will very soon become of great importance and interest to us, which we will therefore discuss in much greater detail when we come to the end of this more or less coherent group formed by Sonnets 1 to 60.

Since I mentioned Horace and Ovid at the beginning, I should take this opportunity to point to the passages in Horace and Ovid that prompt scholars to believe Shakespeare was inspired by them, and it is easy to see how they come to this conclusion:

Horace, in his Odes, writes, here in the translation by James Michie in the Penguin Classics edition:

More durable than bronze, higher than Pharaoh's

Pyramids is the monument I have made,

A shape that angry wind or hungry rain

Cannot demolish, nor the innumerable

Ranks of the years that march in centuries.

I shall not wholly die: some part of me

Will cheat the goddess of death, for while High Priest

And Vestal climb our Capitol in a hush,

My reputation shall keep green and growing.

Arthur Golding, who was a contemporary of Shakespeare's, although a generation older, wrote a seminal translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses, and we know with great certainty that Shakespeare knew this book and used it extensively for inspiration, because he frequently references it and in some cases borrows near verbatim quotations. There we find:

Now have I brought a work to end which neither Jove's fierce wrath,

Nor sword, nor fire, nor fretting age with all the force it hath

Are able to abolish quite. Let come that fatal hour

Which (saving of this brittle flesh) hath over me no power,

And at his pleasure make an end of mine uncertain time.

Yet shall the better part of me assured be to climb

Aloft above the starry sky. And all the world shall never

Be able for to quench my name. For look how far so ever

The Roman Empire by the right of conquest shall extend,

So far shall all folk read this work. And time without all end

(If poets as by prophecy about the truth may aim)

My life shall everlastingly be lengthened still by fame.

Fascinating about this latter passage is that, short though it be, it contains several turns of phrase that have a familiar ring to us from Shakespeare, even beyond Sonnet 55: "the better part of me," "all the world," "time without all end" all sound decidedly Shakespearean to us, because they were clearly currency then, and Golding's Ovid very obviously helped form Shakespeare's style.

One more observation should be made that is pertinent not only to this Sonnet 55, but in fact to all the sonnets since what I have referred to and like to think of as the 'reunion' that followed an obvious period of separation. From Sonnet 52 onwards, Shakespeare has been addressing his young man as 'you' again.

'Again' here is an operative term: there is a school of thought which holds that the fact alone that Shakespeare addresses some of these poems to their recipient with the familiar 'thou' and some with the more formal 'you' is 'proof' that they must be different individuals. This does not stand up to scrutiny for long though because even within the sequence that makes up the Procreation Sonnets, 1-17, which really are so specific in their intent and so consistent in their characterisation of the addressee that the vast majority of scholars and editors accept they appear to be written to and for the same young man, Shakespeare switches from 'thou' to 'you' several times. There we noted that this seems to be happening on occasions when it would help the poet to acknowledge or signal the stark difference in status between him and the young man, who to all intents and purposes sounds like he is a young nobleman or certainly a person of high social standing. And most tellingly, in Sonnet 24, as the only sonnet in the collection, Shakespeare uses both forms of address, 'you' and 'thou', in the same poem. Sonnet 24 is one we identified as 'complex and quietly insightful', as it reflects the great complexity of Shakespeare's relationship with his young man.

We cannot possibly, therefore, conclude from the fact that Shakespeare sometimes uses 'you' and sometimes 'thou' that he is therefore talking to different people: he clearly uses both forms of address for the same person. That settled, we can then begin to examine what, if any, meaning there is to this group of sonnets, 52 to 58, using the more formal form of address, 'you'. Of course we don't know for certain. But if we latch on once more to this notion of the form of address being a subtle pointer to an awareness of status, then this here once again makes perfect sense.

Sonnet 52 is one we identified as the closest Shakespeare has come so far to answering the question whether or not the relationship between him and his young man is a sexual one. If that is the case, then doing so once again – as he has done before when entering potentially sensitive territory – with a sonnet that speaks to its recipient with a degree of formality and reverence is perhaps not so unwise. He then keeps this going for Sonnet 53, which either salutes the young man for his constancy or chastises him for his inconstancy, we can't possibly be sure which, and this constructive ambiguity again is a bold undertaking by a poet who may be skating on comparatively thin ice, considering the constellation he is in. In Sonnet 54 it is 'my', Shakespeare's, verse that distils 'your', the young man's, truth and therefore truthfulness and authenticity, and here with Sonnet 55 we are still firmly in the land of 'you'.

Sonnet 56 changes register once more completely and addresses not the young man but love itself, but with Sonnets 57 & 58 we are introduced to a whole new level of status awareness and very conscious highlighting of where you, my young man, are in relation to me, the poet, in this world.

Sonnet 55, then, is fascinating for all manner of reasons, but not least because it forms something of an apex on which pivots this whole relationship into a profoundly thought-provoking and in several aspects quite perturbing phase...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!