Sonnet 67: Ah, Wherefore With Infection Should He Live

|

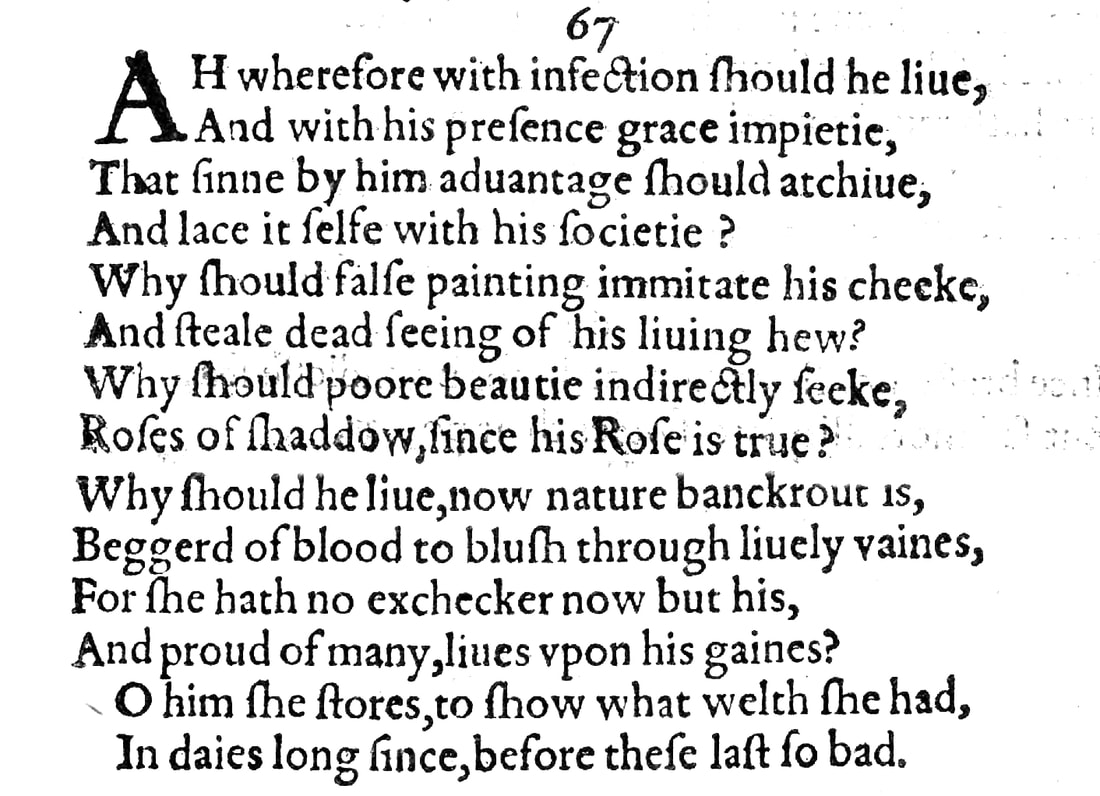

Ah, wherefore with infection should he live

And with his presence grace impiety? That sin by him advantage should achieve And lace itself with his society? Why should false painting imitate his cheek And steal dead seeming of his living hue? Why should poor beauty indirectly seek Roses of shadow, since his rose is true? Why should he live, now nature bankrupt is, Beggared of blood to blush through lively veins? For she hath no exchequer now but his, And, proud of many, lives upon his gains. O him she stores to show what wealth she had In days long since, before these last so bad. |

|

Ah, wherefore with infection should he live

And with his presence grace impiety? |

Ah, why should he live in amongst all this corruption, and with his presence in a morally deprived or sick world grace or adorn impiety, here implying not only irreligious, irreverent behaviour, but a society that lacks or has lost any moral compass.

Shakespeare does not elaborate on who 'he' is, but from what follows it's entirely clear and obvious he is talking about his young lover who is by now well-noted for his beauty, and no-one else. But the phrasing of the opening question and the slightly melodramatic exclamation at its beginning immediately pose the question: how sincere and how literal or poetic is Shakespeare being with this sonnet? In the collection it follows on from Sonnet 66 with its unrelenting enumeration of ills and so ostensibly the 'infection' here referred to could absolutely be simply that of a world thus corrupted. But we can't rule out that our poet is here using his skills to insinuate that the young man himself has been tarnished, either by his behaviour or even physically by contracting an infectious disease, or quite conceivably both, one as the result of the other, but we have to be extremely careful about reading the line so literally. |

|

That sin by him advantage should achieve

And lace itself with his society? |

The question continues: should he live with infection – whatever this infection so referred to here is – just so that sin can benefit from his presence and adorn or beautify itself by associating with him?

The fact that 'sin' now explicitly enters the equation supports the notion, mostly just hinted at in the first two lines, that we are here not only in the context of a societal malaise but also a sexual misdemeanour of some description. "Lace itself with his society" has a gratifying double meaning of, on the one hand, as above, 'decorating itself' with his company, in the way that a garment or a piece of clothing or even a table cloth or a napkin may be made to look pretty with a piece of lace, which would have been highly prized in Shakespeare's day, but also of 'interlacing' itself with him in his company, in the sense of entwining with him. The layering of meanings is unlikely to be a coincidence and lends further impetus to the supposition that there is more at stake here then at one first and single glance might meet the eye... |

|

Why should false painting imitate his cheek

And steal dead seeming of his living hue? |

Why should fake make-up imitate or copy his cheek, for which read his face, and, with an appearance of death, steal of his real-life beauty.

We have noted on at least two previous occasions the disdain Shakespeare reserves for make-up and fakery through cosmetics, and the primary meaning of 'false painting' here is undoubtedly this: the false, for which read fake painted faces that become fashionable around this time, increasingly also for men: the appearance of the fop, with thick layers of face paint, often ghostly white, paired with artificial rosiness in the cheeks and lips, this latter also clearly being alluded and referred to further in the next couple of lines. The fashion for dead pale faces during the second half of the 16th century partly stemmed from the ideal, at the time, of a virginal, snow-white skin, and it was further propagated by Queen Elizabeth I herself, who, after contracting smallpox in 1562, took to wearing increasingly heavy white make-up to cover the blemishes on her face, which gave her the iconic, white-faced appearance we know from several portraits of hers. Whether or not Shakespeare means to also suggest a secondary meaning with 'false painting' of 'flattering and therefore false portraiture' or even, perhaps on a tertiary level, similarly exaggerated poetic representations by other poets, we don't know. It can't be ruled out, and fairly soon in the series we will get strong evidence of another poet encroaching on Will's territory, but the idea of false painting of either of this kind – portrait or poem – stealing 'dead seeming of his living hue' feels rather far-fetched. The Quarto Edition for this line has "dead seeing," which presents the first of two textual problems in this sonnet: opinion is divided over whether 'dead seeing' can mean 'of lifeless appearance' or whether a letter m has gone missing from the manuscript here. Shakespeare does not use the phrase 'dead seeing' anywhere in his entire output, but nor does he use 'dead seeming' anywhere else. In fact he doesn't use 'dead' – a word that appears no fewer than 602 times in his collected works – much in combination with any other word to mean anything other than someone or something being quite literally dead, the exceptions being 'dead night' in Sonnet 43, 'pale-dead' in Henry V, 'dead midnight' in Measure for Measure and Richard III, 'dead drunk' in Othello where, incidentally, he also uses "after long seeming dead" – which is not the same as 'dead seeming' but comes close – 'dead time' in Richard II, 'dead-killing' in Richard III and The Rape of Lucrece, 'dead silence' in Two Gentlemen of Verona, and 'dead-cold' in The Two Noble Kinsmen, whereby the latter is usually now attributed to William Shakespeare in collaboration with John Fletcher. In light of all this, I am inclined here to adopt the emendation to 'dead-seeming'. |

|

Why should poor beauty indirectly seek

Roses of shadow, since his rose is true? |

Why should poor beauty seek fake roses – roses that are mere shadows of the real thing – when his, my lover's, rose is genuine.

In other words: why should beauty itself, which is to be pitied in a world like this and therefore poor, go around looking for ways to beautify other people with artificial rosiness in their cheeks, when his beauty is, as we have heard many times before, the real thing. |

|

Why should he live, now nature bankrupt is,

Beggared of blood to blush through lively veins? |

Why should he even live, now that nature is bankrupt, bereft of blood to run through veins and lending her life: nature itself has been robbed, in this appalling world of fakery and ghastly pretend-beauty, and is left with no blood to course through her body. This echos the dead seeming mask-like appearance of these heavily made-up faces.

William Shakespeare is not one to go all out for bold alliterations wherever he can: he tends to use the device fairly sparingly. Not here though, and the words are so ruddily evocative, it's hard to resist the temptation to find that he is being deliberately provocative: Beggared of blood to blush through lively veins. If you say this out loud with even a hint of dismay in your voice, you get a sound that is more than a little reminiscent of 'buggered', which at around the time of Shakespeare comes to acquire its sexually explicit and also illicit meaning. For a wordsmith of Shakespeare's calibre not to be aware of this is all but inconceivable, and in combination with 'infection', 'sin', and 'blush', we can probably say that there is some serious punning intended here. |

|

For she hath no exchequer now but his,

And, proud of many, lives upon his gains. |

Because she, nature, now, today, has no treasury – implied is treasury of beauty – left except his, meaning that he is the last beautiful treasure she has and so she now lives upon 'his gains': whatever metaphorical 'interest' the 'investment' that he represents may yield.

The sonnet's second textual issue comes with 'proud of many': some editors emend this to 'prived of many', to suggest that nature is now deprived of many, indeed most, or in fact all, other treasuries of beauty that she once held. This would certainly make sense. Sort of. And the suggestion that a typesetter might misread a manuscript's 'prived' for 'proud' is entirely plausible. It therefore is very inviting indeed to adopt this, but 'proud' also makes some sort of sense: personified nature could be understood as being immodestly proud of many other, lesser, beauties that she has, whilst actually drawing any real sustenance she gets from him. Neither of these two readings is wholly satisfactory, but my approach is to not mess with the words that we have unless absolutely necessary, and so since there is no obvious or compelling solution on offer for the conundrum presented by this line, I am inclined to leave this untouched. |

|

O him she stores to show what wealth she had

In days long since, before these last so bad. |

Oh, him – my lover – she – nature – keeps in store as the last remaining example to show the world what extraordinary wealth she used to have, in the long distant past, before these recent days, including the ones we are living through now, which are so absolutely appalling.

|

Sonnet 67 picks up on the deeply dissatisfied mood of Sonnet 66 and develops the theme of a world that has lost its way right through Sonnet 68. On the surface, Sonnets 67 & 68 concern themselves entirely with the then relatively new fashion – much scorned by Shakespeare – for heavy make-up and big wigs and their wearers' futile endeavours to endow themselves with a fake and therefore ghastly pseudo-beauty that stands in such stark contrast to his young lover's natural and therefore genuine beauty. But Sonnet 67 also – and unlike Sonnet 68 – employs several layered phrases and some obvious as well as some more dubious double meanings that may hint at an underlying unease about the young man's conduct or the state of his reputation, the two of which go together. This, while at best subtly suggested in Sonnet 67, will become the direct subject of Sonnets 69 & 70, and once again, far more forcefully still, in Sonnets 94, 95, and 96.

As always when dealing with pairs, we will look at Sonnets 67 & 68 together in the next episode, while focusing on the first one, Sonnet 67, in this one.

We have asked ourselves once or twice before when listening to a sonnet by William Shakespeare: what brings this on? Sonnet 67, coming so hard on the heels of Sonnet 66, in which everything is basically wrong with the world, appears to only partly pose this question: in a culture as bad as the one portrayed in Sonnet 66, the despicable habit of people – men as well as women – to cake themselves in layers of make-up is just one more thing to abhor. We already know what Shakespeare thinks of make-up and of fake 'beauty' in general.

We first get a whiff of his umbrage in Sonnet 20 where he notes that the young man does have the face of a woman, but distinguishes it as one that is "with Nature's own hand painted," in contrast to the artificial face paint worn by women at the time. Immediately after, in Sonnet 21, he speaks of the Muse who is "stirred by a painted beauty to his verse," again drawing a clear distinction between himself and that kind of poet, making it clear that the beauty that inspires him is of a different category entirely. Within the sonnets, this here is the strongest expression yet of his displeasure, referring to "false painting" that 'imitates' the real beauty of his lover and is found to be either "dead seeing" or "dead seeming" and in any case 'stealing' from his genuine hue.

Still, it is hard to believe that there is nothing else to it. True enough: when we find ourselves agitated about things that upset us, then another thing that riles us may well prompt a complementary outburst. That is not overly puzzling. What makes us do the equivalent of a double take is the language deployed and the vehemence with which Shakespeare vents his spleen. But we are, once more, in the realm of conjecture here if we start drawing conclusions. The poem itself does not yield anything resembling any conclusive clues and in fact Sonnet 68, which clearly continues the argument from this one, appears to focus entirely on precisely this cavil of Shakespeare's: beauty being bastardised by artifice. Here in Sonnet 67 it is make-up, in Sonnet 68 it is wigs.

And so maybe we need to contend ourselves with what we have and say: so be it. In the absence of any proof otherwise, let us assume that Shakespeare extends his rant from Sonnet 66 and devotes two entire poems to two personal bugbears, holding up his lover against them as the paradigm of what beauty is and was and should be, and telling the world how wrong it gets things when it comes to beauty too, as well as everything else he's already talked about in 66.

This may strike us as a little anticlimactic, and for the time-being it is. But bear in mind: we are only just approaching the halfway point in the collection. And we haven't even listened to 68 yet. John Kerrigan, in his New Penguin edition of The Sonnets goes as far as to say that "this poem – especially in the wake of 66 with its self-pitying lament – marks a crucial stage in the poet's account of the youth," and this may yet prove true for several reasons that will become clearer as we go on: we seem to be entering a phase with Sonnet 67, in which William Shakespeare gets ever more painfully torn between his love for the young man and the things – real or imagined – that his young man gets up to or is reputed to be getting up to, between his own age, reputation, and status as compared to that of the young lover, and between his need of the young lover's approval and the young lover's soon to become evident interest in another writer's attentions, which either are or at any rate seem to William Shakespeare to be of more than a purely poetic nature.

What makes matters worse for Will is that unlike the critical episode that starts with Sonnet 33 where he very obviously finds out exactly what has been going on and equally obviously receives the kind of apology – express or conveyed in remorse – that allows him to swiftly forgive the youth his straying ways, in the crisis that currently unfolds he seems to be as much at a loss as we are. Or, perhaps more accurately and more to the point: if we feel at a loss, then it may well be because William Shakespeare is at a loss. Not just, as we saw in the 'self-pitying', yes, but also heartfelt, viscerally lived lament of 66, at the end of his tether but also totally out of sorts.

Our poet, we get the impression, starting with Sonnet 67, and increasingly so from now on in for quite some time, doesn't know whether he's coming or going, whether he's being humoured or hated, respected or rejected, loved or left by the wayside. And this may account for one particularly noteworthy facet of Sonnets 67 & 68 that we haven't actually properly noted yet: in this pair, William Shakespeare talks about his young man as 'he', in the third person singular. Not, as he did in the astonishingly self-abasing Sonnets 57 & 58 and in the much more philosophically settled Sonnet 59 as 'you', not, as in Sonnets 60 through 62, as 'thou', but, as in fact has been the case since Sonnet 63, as 'he'. Except that curiously of this batch, only Sonnet 63 actually refers to him as 'he', and it also, as we observed at the time, speaks of 'him' explicitly as 'my love'. Sonnet 64, for all its gorgeous melancholy beauty, does not refer to the young man as either 'love' or 'he' or 'you' or 'thou', but as "that which it fears to lose," where 'it' is a thought that is "as a death." Sonnet 65 again talks about the lover in the third person, as 'my love' but without calling him 'he', and exactly the same is true of Sonnet 66.

If this invites, as for some people it does, any suggestion that these two sonnets could therefore be about a man or a woman, with Sonnets 67 & 68 any gender-ambiguity – however tentative, so as not to say spurious in the larger context of the sonnets it may be – is swept off the table: these two sonnets talk about a man in the third person singular.

But talking about the person you love in the third person without having introduced them as your love is oddly impersonal. It is something that – should you be as interested in these nuances as I am – has rarely happened before: Sonnet 19, right at the beginning of the series as we know it, addresses itself to Time and speaks about 'my love's fair brow', and also identifies him unmistakably as a 'he'. Sonnet 21 is the first sonnet addressed to a general audience and refers to 'my love' without specifying their gender, but this coming immediately after Sonnet 20 which spells out the fact that Shakespeare's love is a man who looks like a woman, wondering greatly at that juncture about their gender would seem disingenuous to the point of being obtuse.

Sonnet 25 is unique in that it does not mention the lover by any term or pronoun, but simply concludes "Then happy I that love and am beloved | Where I may not remove nor be removed." Sonnet 28 doesn't mention the love except in indirect speech, but it comes in a strong pairing with Sonnet 27 which refers to the lover as 'thee' and 'thy', for which read 'thou'. Then we come to Sonnet 33 which marks the beginning of the outrage of the young lover's fling with Shakespeare's own mistress and this is the first and thus far only time where Shakespeare addresses a general, unspecified reader or listener, and talks about his lover as 'he', having first named him as 'my sun' to compare him with the actual sun in the sky. Sonnet 56, just for the sake of completeness, doesn't refer to the lover at all in any way, but addresses itself to love itself and asks it to renew itself.

What do we get from all this? We mostly get the idea that Shakespeare is – just as we thought and knew and always felt – only human. He does exactly what you or I do when we are upset about the person we love: he refers to them in the third person singular. He talks about him, not to him. How often have you encountered a couple at a party or a dinner where suddenly one person talks about the other, mentioning things that irk them? "I would love to go to fishing, but he has decided to turn vegan." "She won't let me buy the llama for our garden." "He gets ever so tetchy, he does." Granted, "Ah, wherefore with infection should he live | And with his presence grace impiety" is in something of a different league, but then it would be: its a Shakespeare sonnet, after all.

Going, as we are, by the words and the words alone, or as alone as we believe we can, we can take note of the fact that Shakespeare, only really properly for the second time in the series, switches to talking about his lover as 'he' while addressing a general audience, and that the first time he did so he did so when he had reason to be upset about his lover. Sonnet 67 somewhat hints at there being an underlying issue, which is something Sonnet 68 won't do. But Sonnet 69 most certainly will, and it will do so in a manner that may yet suffice to make the odd jaw drop...

As always when dealing with pairs, we will look at Sonnets 67 & 68 together in the next episode, while focusing on the first one, Sonnet 67, in this one.

We have asked ourselves once or twice before when listening to a sonnet by William Shakespeare: what brings this on? Sonnet 67, coming so hard on the heels of Sonnet 66, in which everything is basically wrong with the world, appears to only partly pose this question: in a culture as bad as the one portrayed in Sonnet 66, the despicable habit of people – men as well as women – to cake themselves in layers of make-up is just one more thing to abhor. We already know what Shakespeare thinks of make-up and of fake 'beauty' in general.

We first get a whiff of his umbrage in Sonnet 20 where he notes that the young man does have the face of a woman, but distinguishes it as one that is "with Nature's own hand painted," in contrast to the artificial face paint worn by women at the time. Immediately after, in Sonnet 21, he speaks of the Muse who is "stirred by a painted beauty to his verse," again drawing a clear distinction between himself and that kind of poet, making it clear that the beauty that inspires him is of a different category entirely. Within the sonnets, this here is the strongest expression yet of his displeasure, referring to "false painting" that 'imitates' the real beauty of his lover and is found to be either "dead seeing" or "dead seeming" and in any case 'stealing' from his genuine hue.

Still, it is hard to believe that there is nothing else to it. True enough: when we find ourselves agitated about things that upset us, then another thing that riles us may well prompt a complementary outburst. That is not overly puzzling. What makes us do the equivalent of a double take is the language deployed and the vehemence with which Shakespeare vents his spleen. But we are, once more, in the realm of conjecture here if we start drawing conclusions. The poem itself does not yield anything resembling any conclusive clues and in fact Sonnet 68, which clearly continues the argument from this one, appears to focus entirely on precisely this cavil of Shakespeare's: beauty being bastardised by artifice. Here in Sonnet 67 it is make-up, in Sonnet 68 it is wigs.

And so maybe we need to contend ourselves with what we have and say: so be it. In the absence of any proof otherwise, let us assume that Shakespeare extends his rant from Sonnet 66 and devotes two entire poems to two personal bugbears, holding up his lover against them as the paradigm of what beauty is and was and should be, and telling the world how wrong it gets things when it comes to beauty too, as well as everything else he's already talked about in 66.

This may strike us as a little anticlimactic, and for the time-being it is. But bear in mind: we are only just approaching the halfway point in the collection. And we haven't even listened to 68 yet. John Kerrigan, in his New Penguin edition of The Sonnets goes as far as to say that "this poem – especially in the wake of 66 with its self-pitying lament – marks a crucial stage in the poet's account of the youth," and this may yet prove true for several reasons that will become clearer as we go on: we seem to be entering a phase with Sonnet 67, in which William Shakespeare gets ever more painfully torn between his love for the young man and the things – real or imagined – that his young man gets up to or is reputed to be getting up to, between his own age, reputation, and status as compared to that of the young lover, and between his need of the young lover's approval and the young lover's soon to become evident interest in another writer's attentions, which either are or at any rate seem to William Shakespeare to be of more than a purely poetic nature.

What makes matters worse for Will is that unlike the critical episode that starts with Sonnet 33 where he very obviously finds out exactly what has been going on and equally obviously receives the kind of apology – express or conveyed in remorse – that allows him to swiftly forgive the youth his straying ways, in the crisis that currently unfolds he seems to be as much at a loss as we are. Or, perhaps more accurately and more to the point: if we feel at a loss, then it may well be because William Shakespeare is at a loss. Not just, as we saw in the 'self-pitying', yes, but also heartfelt, viscerally lived lament of 66, at the end of his tether but also totally out of sorts.

Our poet, we get the impression, starting with Sonnet 67, and increasingly so from now on in for quite some time, doesn't know whether he's coming or going, whether he's being humoured or hated, respected or rejected, loved or left by the wayside. And this may account for one particularly noteworthy facet of Sonnets 67 & 68 that we haven't actually properly noted yet: in this pair, William Shakespeare talks about his young man as 'he', in the third person singular. Not, as he did in the astonishingly self-abasing Sonnets 57 & 58 and in the much more philosophically settled Sonnet 59 as 'you', not, as in Sonnets 60 through 62, as 'thou', but, as in fact has been the case since Sonnet 63, as 'he'. Except that curiously of this batch, only Sonnet 63 actually refers to him as 'he', and it also, as we observed at the time, speaks of 'him' explicitly as 'my love'. Sonnet 64, for all its gorgeous melancholy beauty, does not refer to the young man as either 'love' or 'he' or 'you' or 'thou', but as "that which it fears to lose," where 'it' is a thought that is "as a death." Sonnet 65 again talks about the lover in the third person, as 'my love' but without calling him 'he', and exactly the same is true of Sonnet 66.

If this invites, as for some people it does, any suggestion that these two sonnets could therefore be about a man or a woman, with Sonnets 67 & 68 any gender-ambiguity – however tentative, so as not to say spurious in the larger context of the sonnets it may be – is swept off the table: these two sonnets talk about a man in the third person singular.

But talking about the person you love in the third person without having introduced them as your love is oddly impersonal. It is something that – should you be as interested in these nuances as I am – has rarely happened before: Sonnet 19, right at the beginning of the series as we know it, addresses itself to Time and speaks about 'my love's fair brow', and also identifies him unmistakably as a 'he'. Sonnet 21 is the first sonnet addressed to a general audience and refers to 'my love' without specifying their gender, but this coming immediately after Sonnet 20 which spells out the fact that Shakespeare's love is a man who looks like a woman, wondering greatly at that juncture about their gender would seem disingenuous to the point of being obtuse.

Sonnet 25 is unique in that it does not mention the lover by any term or pronoun, but simply concludes "Then happy I that love and am beloved | Where I may not remove nor be removed." Sonnet 28 doesn't mention the love except in indirect speech, but it comes in a strong pairing with Sonnet 27 which refers to the lover as 'thee' and 'thy', for which read 'thou'. Then we come to Sonnet 33 which marks the beginning of the outrage of the young lover's fling with Shakespeare's own mistress and this is the first and thus far only time where Shakespeare addresses a general, unspecified reader or listener, and talks about his lover as 'he', having first named him as 'my sun' to compare him with the actual sun in the sky. Sonnet 56, just for the sake of completeness, doesn't refer to the lover at all in any way, but addresses itself to love itself and asks it to renew itself.

What do we get from all this? We mostly get the idea that Shakespeare is – just as we thought and knew and always felt – only human. He does exactly what you or I do when we are upset about the person we love: he refers to them in the third person singular. He talks about him, not to him. How often have you encountered a couple at a party or a dinner where suddenly one person talks about the other, mentioning things that irk them? "I would love to go to fishing, but he has decided to turn vegan." "She won't let me buy the llama for our garden." "He gets ever so tetchy, he does." Granted, "Ah, wherefore with infection should he live | And with his presence grace impiety" is in something of a different league, but then it would be: its a Shakespeare sonnet, after all.

Going, as we are, by the words and the words alone, or as alone as we believe we can, we can take note of the fact that Shakespeare, only really properly for the second time in the series, switches to talking about his lover as 'he' while addressing a general audience, and that the first time he did so he did so when he had reason to be upset about his lover. Sonnet 67 somewhat hints at there being an underlying issue, which is something Sonnet 68 won't do. But Sonnet 69 most certainly will, and it will do so in a manner that may yet suffice to make the odd jaw drop...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!