Sonnet 7: Lo! In the Orient When the Gracious Light

|

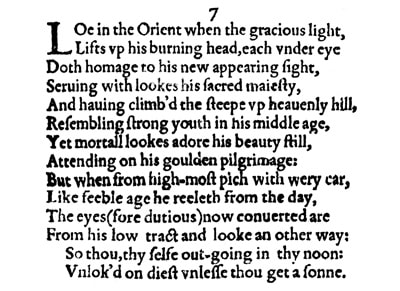

Lo! In the orient when the gracious light

Lifts up his burning head, each under-eye Doth homage to his new-appearing sight, Serving with looks his sacred majesty; And, having climbed the steep-up heavenly hill, Resembling strong youth in his middle age, Yet mortal looks adore his beauty still, Attending on his golden pilgrimage. But when from highmost pitch with weary car, Like feeble age he reeleth from the day, The eyes, fore duteous, now converted are From his low tract and look another way. So thou, thyself outgoing in thy noon Unlooked on diest, unless thou get a son. |

|

Lo! In the orient when the gracious light

Lifts up his burning head |

Look! In the east, when the sun rises...

'Lo!' – sometimes written with an exclamation mark, sometimes separated from the rest of the sentence by a comma, sometimes, as in the original publication, the Quarto Edition, simply part of the sentence, is an expression to draw attention to something that is worthy of that attention, that is either extraordinary, or amazing, or unusual, as in: 'lo and behold: the politician saw sense and retired from office voluntarily.' It is interesting therefore that Shakespeare starts his seventh sonnet with this little but powerful word, to draw attention to something that is on the surface quite common: the rising of the sun: the "gracious light" that "lifts up his burning head." |

|

each under-eye

Doth homage to his new-appearing sight, |

...each eye on earth – by implication that is every human eye – which is both physically underneath the sun and also of inferior status because the sun is, after all, the life-giving celestial body that effectively 'rules' our planet, so each "under-eye" declares its allegiance to this renewed and regular appearance of the sun...

|

|

Serving with looks his sacred majesty;

|

...and serves this sacred or holy majesty of the sky by paying attention to, and looking at, it.

In other words: in the morning, when the sun's appearance is new and young, everybody is in awe of it. |

|

And, having climbed the steep-up heavenly hill,

|

And, having risen in the sky...

The steep-up heavenly hill is the arc the sun travels during its ascent, and "steep-up" simply means steep in an upward direction. PRONUNCIATION: Note that heavenly here is pronounced with two syllables: hea'n-ly. |

|

Resembling strong youth in his middle age,

|

...all the while having an appearance similar to that of its youth in the morning, even though it is now at midday, which is the daily sun's equivalent to a human's middle age...

|

|

Yet mortal looks adore his beauty still,

|

...humans still look at his, the sun's, beauty with admiration...

The "yet" here has the same meaning as 'nevertheless' or 'even so', meaning that even though the sun is now in its middle age, we humans still find it amazingly beautiful. |

|

Attending on his golden pilgrimage.

|

...and in doing so – in looking at the sun – human eyes attend him, in the sense of a servant attending on a king: reverentially and subordinately.

The "golden pilgrimage" reminds us that this is no earthly or mortal king, we are talking about here, it is a "sacred majesty:" it is effectively divine. |

|

But when from highmost pitch with weary car,

Like feeble age he reeleth from the day, |

But when he – the sun – with his tired carriage – the horses in a horse-drawn carriage are being taken as read in an age when there were only cars with literal horsepower – careers or 'staggers' or indeed 'reels' from the zenith, the highest point, which is midday and therefore stands for the day itself, now moving down toward the evening, looking and seeming "like feeble age," like a weak old man...

|

|

The eyes, fore duteous, now converted are

From his low tract and look another way. |

...these human eyes which before were dutiful are now averted – "converted" is an old version of the same word, meaning turned away – from his, the sun's, path as it now lies low in the sky, and they do what 'averted eyes' must do: they look "another way," at something else; by implication something more beautiful than this sun, old as it now is, something more majestic, more powerful, altogether more interesting.

|

|

So thou, thyself outgoing in thy noon

|

In the same way you, when you yourself are beginning to leave the 'daytime' of your life and start to move out to the evening after you've reached your high point around middle age...

|

|

Unlooked on diest, unless thou get a son.

|

...will die without anyone paying the least attention to you or even looking at you, unless of course you do as I've been telling you for seven sonnets now including this one, and produce a son.

PRONUNCIATION: Note that diest here has one syllable: di'st. |

Sonnet 7 is fascinating in that it employs a somewhat unsuccessful metaphor to implore the young man to have a child, but it nevertheless tells us yet more about Shakespeare, his way of writing poetry, and the culture he works in.

The young man is presented with the example of the sun that rises in the morning, beautiful and bright, new and young and in its majestic, even sacred appearance, it commands the attention of everyone beneath: every human eye is compelled by this brilliant and powerful presence and willing to pay attention to it and even serve it. We would today perhaps speak of sun worship.

But as the sun descends from its highest point at noon and moves towards the evening, it weakens in power, it begins to look and feel like an old sun compared to its fresh youth in the morning, and as a direct consequence of this, people lose interest in it, but also respect, and far from attending or let alone serving it, they simply look another way.

The argument thus established, the young man is then told that this exact same thing will happen to him: while he is young and enjoys the full brilliance of his beauty, people of course look at him and pay attention to him and behave in a manner that is dutiful, even servile. But as he loses his power and his status and most certainly also his beauty, people will lose interest in him because he himself will no longer be much to look at, but also – and this is not unimportant in this context – his name, his estate, his standing in the world will be substantially diminished, unless he has a son who can, as we heard before, carry on both his beauty and also, importantly, his name.

The reason the metaphor doesn't quite work is twofold: firstly, one could argue — and from a contemporary perspective we almost certainly would — that the sun is just as beautiful in the evening as it is in the morning. Acknowledging that this is a contemporary perspective though may be crucial.

We have noted before that these sonnets tell us something about how closely enmeshed with the seasons and the cycle of life human existence is during Shakespeare's day, and this certainly also applies to the perception of the sun. The sun is a life giver, it is the source of energy and sustenance, and it is extremely mighty, during the day. Its majesty, its power does however absolutely wane in the evening and so we should not be surprised that in an age before tourism, before beach holidays, before 'leisure' time in a contemporary sense, or holidays as we understand them today, people did not pay anywhere near as much attention to sunsets as we have been doing more or less ever since the Romantic period, which peaks roughly 200 yers after these sonnets were written.

The second aspect in which the metaphor doesn't quite stack up is that the sun does not, of course, produce any offspring. It simply sets in the west and then rises again in the east. The sun's new appearance is just that: a new appearance of the same old sun.

If we felt so inclined we could be a little pedantic and furthermore point out that actually doing "homage" to the sun's "new appearing sight" by "serving" it with "looks" is ill advised. If you look at the sun directly, then as now, you blind yourself and do potentially severe damage to your eyesight, so people tend not to do it. Neither now nor then.

So the question, when we have in front of us a well-structured and predictably well-composed poem, that does, however, fail somewhat to convince on its own internal logic, is, once again: why? Where does this come from? What prompts Shakespeare to write this sonnet, in this way?

And as we have been saying and as you will keep hearing me reiterate often: we don't know. Certainly not for certain. But there are two mutually non-exclusive possible pointers towards an explanation, meaning that they may well both apply at the same time and for different reasons.

The first one is a literary one. And this is as good a moment as any to observe – as many scholars do and often emphasise quite strongly – that Shakespeare of course does not compose in isolation. He is not an abstract intelligence that works entirely from within its own imagination. He is an English poet with – in all likelihood and as everything we know about him suggests – a coherent education in the English tradition of the time, and that entails the classics: Roman and Greek mythology, including, most specifically, Ovid. Many parallels, many indirect or even direct references can be found in Shakespeare to Ovid, and classical mythology permeates Shakespeare's entire body of work. And so the concept of the Sun as a god who travels across the sky, resplendent in a carriage drawn by fiery horses, is obviously not new. It's of Greek classical origin. And so employing it to make a rhetorical point is therefore also far from new: it's a standard rhetorical device, it's a trope, something you can 'take off the shelf' and use in your argument. And Shakespeare's audience – and for the purpose of this sonnet we can only assume that the audience is this one young man – this commonplace, that of the Sun as a god to whom one could be compared to – would have been instantly recognisable.

There would have been very little need for anyone to attempt a detailed analysis of this metaphor or to criticise it for its logical flaws, it would have been accepted as a stock reference and its meaning immediately understood.

The second reason, and this may – as just pointed out – very well go hand-in-hand with the first one, is one we mentioned once before: if – as is entirely possible, but as yet unproven – William Shakespeare did not write these first few sonnets in the standard sequence on his own initiative, but was in fact commissioned to write them, then his relying on a rhetorical device such as this makes perfect sense: he still has, as far as we can tell, no real personal investment in his as yet virtually non-existent relationship with the young man; so all he both can and needs to do is fulfil his assignment, which is to write poetry which will encourage the young man to follow the advice and counsel given therein.

Sonnet 7 then stands there, a bit more than a third into the Procreation Sequence, and on the surface does little besides what it is meant to do. It does not seem – at least as far as we can tell or have so far deciphered – to contain any hidden message or meaning, it does not communicate any personal emotion, it does not break any boundaries. In fact, almost the opposite: it is a classically composed piece that employs classical imagery to make a classic point: it, in a sense, knows its own limitations and sticks to them. And in doing so it shows us what these boundaries are and what the cultural context within which it is being created.

It is not the only sonnet in this Procreation Sequence to do so, but there will be some soon that categorically break this very strongly signalled mould...

The young man is presented with the example of the sun that rises in the morning, beautiful and bright, new and young and in its majestic, even sacred appearance, it commands the attention of everyone beneath: every human eye is compelled by this brilliant and powerful presence and willing to pay attention to it and even serve it. We would today perhaps speak of sun worship.

But as the sun descends from its highest point at noon and moves towards the evening, it weakens in power, it begins to look and feel like an old sun compared to its fresh youth in the morning, and as a direct consequence of this, people lose interest in it, but also respect, and far from attending or let alone serving it, they simply look another way.

The argument thus established, the young man is then told that this exact same thing will happen to him: while he is young and enjoys the full brilliance of his beauty, people of course look at him and pay attention to him and behave in a manner that is dutiful, even servile. But as he loses his power and his status and most certainly also his beauty, people will lose interest in him because he himself will no longer be much to look at, but also – and this is not unimportant in this context – his name, his estate, his standing in the world will be substantially diminished, unless he has a son who can, as we heard before, carry on both his beauty and also, importantly, his name.

The reason the metaphor doesn't quite work is twofold: firstly, one could argue — and from a contemporary perspective we almost certainly would — that the sun is just as beautiful in the evening as it is in the morning. Acknowledging that this is a contemporary perspective though may be crucial.

We have noted before that these sonnets tell us something about how closely enmeshed with the seasons and the cycle of life human existence is during Shakespeare's day, and this certainly also applies to the perception of the sun. The sun is a life giver, it is the source of energy and sustenance, and it is extremely mighty, during the day. Its majesty, its power does however absolutely wane in the evening and so we should not be surprised that in an age before tourism, before beach holidays, before 'leisure' time in a contemporary sense, or holidays as we understand them today, people did not pay anywhere near as much attention to sunsets as we have been doing more or less ever since the Romantic period, which peaks roughly 200 yers after these sonnets were written.

The second aspect in which the metaphor doesn't quite stack up is that the sun does not, of course, produce any offspring. It simply sets in the west and then rises again in the east. The sun's new appearance is just that: a new appearance of the same old sun.

If we felt so inclined we could be a little pedantic and furthermore point out that actually doing "homage" to the sun's "new appearing sight" by "serving" it with "looks" is ill advised. If you look at the sun directly, then as now, you blind yourself and do potentially severe damage to your eyesight, so people tend not to do it. Neither now nor then.

So the question, when we have in front of us a well-structured and predictably well-composed poem, that does, however, fail somewhat to convince on its own internal logic, is, once again: why? Where does this come from? What prompts Shakespeare to write this sonnet, in this way?

And as we have been saying and as you will keep hearing me reiterate often: we don't know. Certainly not for certain. But there are two mutually non-exclusive possible pointers towards an explanation, meaning that they may well both apply at the same time and for different reasons.

The first one is a literary one. And this is as good a moment as any to observe – as many scholars do and often emphasise quite strongly – that Shakespeare of course does not compose in isolation. He is not an abstract intelligence that works entirely from within its own imagination. He is an English poet with – in all likelihood and as everything we know about him suggests – a coherent education in the English tradition of the time, and that entails the classics: Roman and Greek mythology, including, most specifically, Ovid. Many parallels, many indirect or even direct references can be found in Shakespeare to Ovid, and classical mythology permeates Shakespeare's entire body of work. And so the concept of the Sun as a god who travels across the sky, resplendent in a carriage drawn by fiery horses, is obviously not new. It's of Greek classical origin. And so employing it to make a rhetorical point is therefore also far from new: it's a standard rhetorical device, it's a trope, something you can 'take off the shelf' and use in your argument. And Shakespeare's audience – and for the purpose of this sonnet we can only assume that the audience is this one young man – this commonplace, that of the Sun as a god to whom one could be compared to – would have been instantly recognisable.

There would have been very little need for anyone to attempt a detailed analysis of this metaphor or to criticise it for its logical flaws, it would have been accepted as a stock reference and its meaning immediately understood.

The second reason, and this may – as just pointed out – very well go hand-in-hand with the first one, is one we mentioned once before: if – as is entirely possible, but as yet unproven – William Shakespeare did not write these first few sonnets in the standard sequence on his own initiative, but was in fact commissioned to write them, then his relying on a rhetorical device such as this makes perfect sense: he still has, as far as we can tell, no real personal investment in his as yet virtually non-existent relationship with the young man; so all he both can and needs to do is fulfil his assignment, which is to write poetry which will encourage the young man to follow the advice and counsel given therein.

Sonnet 7 then stands there, a bit more than a third into the Procreation Sequence, and on the surface does little besides what it is meant to do. It does not seem – at least as far as we can tell or have so far deciphered – to contain any hidden message or meaning, it does not communicate any personal emotion, it does not break any boundaries. In fact, almost the opposite: it is a classically composed piece that employs classical imagery to make a classic point: it, in a sense, knows its own limitations and sticks to them. And in doing so it shows us what these boundaries are and what the cultural context within which it is being created.

It is not the only sonnet in this Procreation Sequence to do so, but there will be some soon that categorically break this very strongly signalled mould...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!