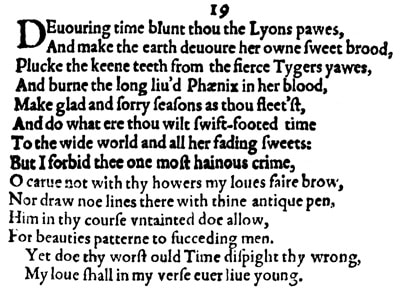

Sonnet 19: Devouring Time, Blunt Thou the Lion's Paws

|

Devouring Time, blunt thou the lion's paws

And make the earth devour her own sweet brood, Pluck the keen teeth from the fierce tiger's jaws, And burn the long-lived Phoenix in her blood; Make glad and sorry seasons as thou fleetst, And do whatever thou wilt, swift-footed time, To the wide world and all her fading sweets, But I forbid thee one most heinous crime: O carve not with thy hours my love's fair brow, Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen; Him in thy course untainted do allow For beauty's pattern to succeeding men. Yet do thy worst, old Time: despite thy wrong My love shall in my verse ever live young. |

|

Devouring Time, blunt thou the lion's paws

And make the earth devour her own sweet brood, |

You, Time, who you eat up and destroy everything as you pass, blunt you the lion's paws and cause the earth itself to consume everything that is born of it, which is every plant and every living thing really, because all things that are born will ultimately return to the earth.

|

|

Pluck the keen teeth from the fierce tiger's jaws

And burn the long-lived Phoenix in her blood. |

Make the fierce tiger's teeth that are keen and eager to tear into the prey's flesh fall out from its jaws as it reaches old age, and even burn up the phoenix: the mythical bird that is said to live for hundreds of years before bursting into flames at the end of its life only to rise again from the ashes.

|

|

Make glad and sorry seasons as thou fleetst,

|

Make happy and sad seasons as you pass by fleetingly...

|

|

And do whatever thou wilt, swift-footed time

|

And do whatever you want, fast-moving time,...

Note that 'whatever' here is pronounced as two syllables: whate'er. |

|

To the wide world and all her fading sweets,

|

...to the wide world and all the beautiful things in it that all fade as you pass...

|

|

But I forbid thee one most heinous crime:

|

...but I forbid you one most heinous crime:

|

|

O carve not with thy hours my love's fair brow

|

Do not carve lines into my love's beautiful face with your hours...

We have had the "forty winters" of Sonnet 2 "besiege thy brow" and the "hours" of Sonnet 5 "play the tyrant" to the "lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell," and here now Time is told not to use 'his' hours to carve the young man's "fair brow," again to mean making his face go wrinkly with age: |

|

Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen:

|

...nor use your old pen to draw lines there.

|

|

Him in thy course untainted do allow

|

Allow him to be unaffected by you as you pass on your "never-resting" course, as I, the poet, called it in Sonnet 5...

|

|

For beauty's pattern to succeeding men.

|

...as a template or indeed model for future generations; the idea being that the young man's beauty should be left intact by Time, so that future generations will know what real beauty looks like and can perhaps model themselves on it.

|

|

Yet do thy worst, old Time: despite thy wrong

My love shall in my verse ever live young. |

Having said all that: do your worst, old Time. Despite of the wrong that you do and have to do – it is after all in your nature as time to make everything turn old, disintegrate and ultimately die – my love will forever live and remain young in this, my poem.

|

The heartfelt, somewhat self-conscious, but defiant and confident Sonnet 19 underlines the bold assertion I, the poet, William Shakespeare, made in Sonnet 18: that it is my poetry itself that gives life to the young man who receives these sonnets, and thus preserves his youth forever.

We are now firmly in new territory. Sonnet 18 with a flourish stepped away from the preoccupation and task of the first 17 sonnets and instead of urging the young man to create a son so as to be able to perpetuate his youthful beauty, told him directly that this, the sonnet itself, will keep him alive "so long as men can breathe or eyes can see." Here now, I, the poet, change tone and mode, but the message is the same: it is this, my sonnet, that will keep my lover young and alive.

The mode is different because rather than speaking to the young man himself, I address Time. And I appear to plead with the old, unimpeachable adversary that makes everything fade and disintegrate and decay and ultimately die, to spare my beautiful young lover, only to then turn around and tell him, Time, that he is powerless against my poetry. It is an astonishing turnaround from three sonnets ago, where I appeared to be suggesting to my love that he could find a "mightier way" and "means more blessed than my barren rhyme" to conquer timer. We realised then, when we were looking at Sonnet 16 and its companion 15 that very probably Shakespeare wasn't being entirely sincere in this assessment. But if we were in any doubt at the time whether or not William Shakespeare really deep down felt that his poetry could save his lover from the ravages of time, by now there is none left. Sonnet 18 already put paid to it, and now, with Sonnet 19, it is dead and buried.

But Sonnet 19 stands out not for this alone, because in this it shares its audacity with Sonnet 18, and 18 arguably surpasses it. What makes Sonnet 19 extraordinary and unique in the series so far is that in it, I, the poet, unequivocally talk about the young man as "my love." For about two centuries until quite recently – the very tail end of the 20th century – people have contorted themselves into trying to argue that somehow this isn't so, that for some reason or other we can or should not interpret these sonnets as William Shakespeare, a man, talking about another, younger man, as his love, and yet he couldn't be much clearer if he tried:

O carve not with thy hours my love's fair brow,

Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen:

Him in thy course untainted do allow

For beauty's pattern to succeeding men.

And what Sonnet 19 also – and equally importantly – does is effectively render pointless any attempt at positioning Sonnet 18 elsewhere, or arguing that Sonnet 18 might just as well be addressed to some other person, for example a young woman. There so very obviously and so very clearly is a progression from Sonnet 17 through Sonnet 18 to Sonnet 19 that the idea that Sonnet 18 might not belong in the sequence or might be meant for somebody else entirely becomes all but ludicrous. And so Sonnet 19 further supports the notion we received throughout the Procreation Sonnets – the first 17 sonnets in the collection – that there is a trajectory, which, though not strictly linear, marks a progression which here continues: the relationship between William Shakespeare and the young man is obviously, clearly evolving. Nothing points towards there being a new cast of principals, everything points towards the same young man being the object of Shakespeare's growing infatuation.

And so while Sonnet 19 on its own makes a strong and emphatic point about the beauty of my young lover and the impotence of Time against the power of my poetry, in the larger context of the constellation between me and my love it may in fact be even more significant than the much more famous Sonnet 18. And also, perhaps, than the much more frivolous and explicit Sonnet 20 that follows, because it tells us that as far as William Shakespeare is concerned, the young man is his love. And of course, it tells the young man the same thing too.

This is not the first time the young man hears himself referred to as 'love': In Sonnet 13, I, the poet, call him "love" first and then "dear my love," but there is a possibility – we observed – that I may be speaking on someone else's behalf there; Sonnet 14 is the first to invoke the idea of the eyes as stars, which is not entirely original but perhaps significant as it is such a well-worn trope in the context of love poetry; in Sonnets 15 and 16 I first propose – as I then do in Sonnets 17, 18, and 19 – that my poetry can serve as the means to make you live forever, and I deploy the unnervingly visceral image of a graft which I apply "for love of you." In Sonnet 16, I backtrack a bit and proffer the somewhat disingenuous "mightier way" of procreation one more time, only to then in Sonnet 17 put that back on a par with my writing. In Sonnet 18 I do not call you anything but the whole tenor of the poem is that of one addressed to a lover. And here now in Sonnet 19 I spell it out: he, the young man, is my love, and no matter what "that bloody tyrant" – as I had called time in Sonnet 16 – is up to, I will make sure that he stays forever young.

You may not be convinced. You may think that perhaps this is all just a little too neat and too well-fitting to seem entirely plausible, that there may be a misunderstanding, or something we're missing, that there may be some wishful thinking involved, or some post-rationalising; that perhaps something got lost in translation, as it were, or in typesetting or that maybe we just shouldn't take "love" here too literally and to mean the kind of passion a man would direct to a romantic lover or love.

And most fortuitously the next sonnet, Sonnet 20, is just about to blow any such doubts right out of the water by squarely addressing the 'issue' of gender head on...

We are now firmly in new territory. Sonnet 18 with a flourish stepped away from the preoccupation and task of the first 17 sonnets and instead of urging the young man to create a son so as to be able to perpetuate his youthful beauty, told him directly that this, the sonnet itself, will keep him alive "so long as men can breathe or eyes can see." Here now, I, the poet, change tone and mode, but the message is the same: it is this, my sonnet, that will keep my lover young and alive.

The mode is different because rather than speaking to the young man himself, I address Time. And I appear to plead with the old, unimpeachable adversary that makes everything fade and disintegrate and decay and ultimately die, to spare my beautiful young lover, only to then turn around and tell him, Time, that he is powerless against my poetry. It is an astonishing turnaround from three sonnets ago, where I appeared to be suggesting to my love that he could find a "mightier way" and "means more blessed than my barren rhyme" to conquer timer. We realised then, when we were looking at Sonnet 16 and its companion 15 that very probably Shakespeare wasn't being entirely sincere in this assessment. But if we were in any doubt at the time whether or not William Shakespeare really deep down felt that his poetry could save his lover from the ravages of time, by now there is none left. Sonnet 18 already put paid to it, and now, with Sonnet 19, it is dead and buried.

But Sonnet 19 stands out not for this alone, because in this it shares its audacity with Sonnet 18, and 18 arguably surpasses it. What makes Sonnet 19 extraordinary and unique in the series so far is that in it, I, the poet, unequivocally talk about the young man as "my love." For about two centuries until quite recently – the very tail end of the 20th century – people have contorted themselves into trying to argue that somehow this isn't so, that for some reason or other we can or should not interpret these sonnets as William Shakespeare, a man, talking about another, younger man, as his love, and yet he couldn't be much clearer if he tried:

O carve not with thy hours my love's fair brow,

Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen:

Him in thy course untainted do allow

For beauty's pattern to succeeding men.

And what Sonnet 19 also – and equally importantly – does is effectively render pointless any attempt at positioning Sonnet 18 elsewhere, or arguing that Sonnet 18 might just as well be addressed to some other person, for example a young woman. There so very obviously and so very clearly is a progression from Sonnet 17 through Sonnet 18 to Sonnet 19 that the idea that Sonnet 18 might not belong in the sequence or might be meant for somebody else entirely becomes all but ludicrous. And so Sonnet 19 further supports the notion we received throughout the Procreation Sonnets – the first 17 sonnets in the collection – that there is a trajectory, which, though not strictly linear, marks a progression which here continues: the relationship between William Shakespeare and the young man is obviously, clearly evolving. Nothing points towards there being a new cast of principals, everything points towards the same young man being the object of Shakespeare's growing infatuation.

And so while Sonnet 19 on its own makes a strong and emphatic point about the beauty of my young lover and the impotence of Time against the power of my poetry, in the larger context of the constellation between me and my love it may in fact be even more significant than the much more famous Sonnet 18. And also, perhaps, than the much more frivolous and explicit Sonnet 20 that follows, because it tells us that as far as William Shakespeare is concerned, the young man is his love. And of course, it tells the young man the same thing too.

This is not the first time the young man hears himself referred to as 'love': In Sonnet 13, I, the poet, call him "love" first and then "dear my love," but there is a possibility – we observed – that I may be speaking on someone else's behalf there; Sonnet 14 is the first to invoke the idea of the eyes as stars, which is not entirely original but perhaps significant as it is such a well-worn trope in the context of love poetry; in Sonnets 15 and 16 I first propose – as I then do in Sonnets 17, 18, and 19 – that my poetry can serve as the means to make you live forever, and I deploy the unnervingly visceral image of a graft which I apply "for love of you." In Sonnet 16, I backtrack a bit and proffer the somewhat disingenuous "mightier way" of procreation one more time, only to then in Sonnet 17 put that back on a par with my writing. In Sonnet 18 I do not call you anything but the whole tenor of the poem is that of one addressed to a lover. And here now in Sonnet 19 I spell it out: he, the young man, is my love, and no matter what "that bloody tyrant" – as I had called time in Sonnet 16 – is up to, I will make sure that he stays forever young.

You may not be convinced. You may think that perhaps this is all just a little too neat and too well-fitting to seem entirely plausible, that there may be a misunderstanding, or something we're missing, that there may be some wishful thinking involved, or some post-rationalising; that perhaps something got lost in translation, as it were, or in typesetting or that maybe we just shouldn't take "love" here too literally and to mean the kind of passion a man would direct to a romantic lover or love.

And most fortuitously the next sonnet, Sonnet 20, is just about to blow any such doubts right out of the water by squarely addressing the 'issue' of gender head on...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!