Sonnet 87: Farewell, Thou Art Too Dear for My Possessing

|

Farewell, thou art too dear for my possessing,

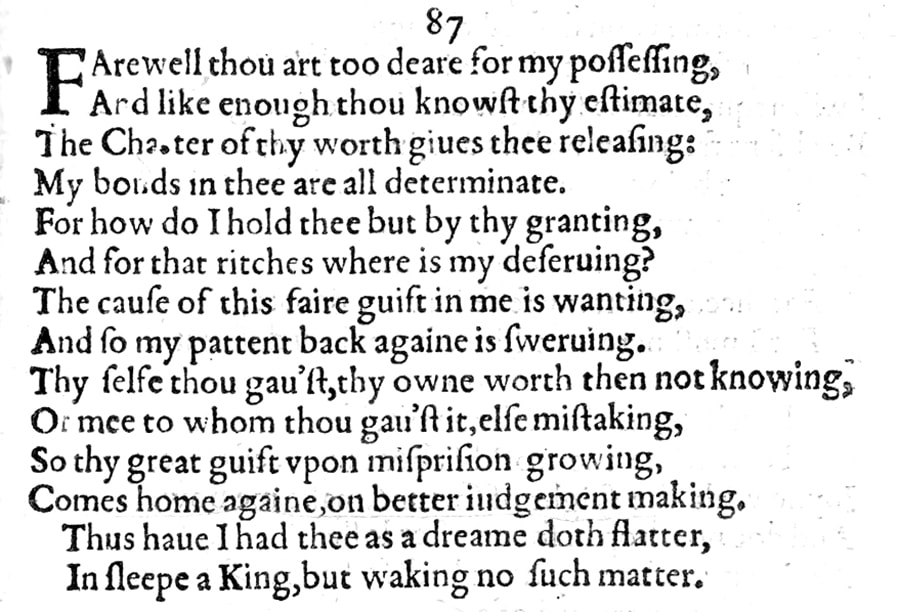

And like enough thou knowst thy estimate; The charter of thy worth gives thee releasing: My bonds in thee are all determinate. For how do I hold thee but by thy granting, And for that riches, where is my deserving? The cause of this fair gift in me is wanting, And so my patent back again is swerving. Thy self thou gavest, thy own worth then not knowing, Or me, to whom thou gavest it, else mistaking, So thy great gift, upon misprision growing, Comes home again on better judgement making. Thus have I had thee as a dream doth flatter: In sleep a king, but waking no such matter. |

|

Farewell, thou art too dear for my possessing,

And like enough thou knowst thy estimate; |

Goodbye, you are too precious, indeed too costly, for me to possess you, and very likely you know your own worth...

'Farewell' is of course in its implications much stronger than a mere 'goodbye': it suggests a conclusive departure forever or for a very long time. Today it is – not least perhaps because of its finality – no longer much in use, and even in Shakespeare's day it is not what you say to someone when you expect to see them the following week, it is what you say to someone who is leaving for good, at least for the foreseeable future. And 'dear' is suitably complex and layered for such a highly charged moment. It means 'loved' and 'appreciated', as in 'my dear friend', but here in tandem with 'possessing' it immediately establishes the strong transactional, financial, and legal connotations that run through the entire sonnet, which in turn are obviously at the same time also metaphorical. 'Too dear' thus becomes 'too expensive' in the sense also of too emotionally unaffordable, and therefore both priced and prized too highly for me to be able to maintain and entertain you as my friend and lover any longer. |

|

The charter of thy worth gives thee releasing,

My bonds in thee are all determinate. |

The document that confirms your legal entitlements and ownership of land and other property is formulated in such terms that it releases you from any commitment or obligation to me: any kind of contract or agreement between us that would give me any right or title in you is terminated and therefore null and void.

A 'charter' in this context specifically can be a royally sanctioned certification, as in a 'royal charter', that lends the young lover his status and his privileges, and the choice of this word here strongly points – as we have long sensed – towards this young man being highly and well connected, it supports the contention that he is a young nobleman. |

|

For how do I hold thee but by thy granting,

And for that riches, where is my deserving? |

Because how do I have you and how am I able to hold on to you and keep you other than with your own permission and by your own gift, and yet how do I deserve such great riches?

There is a basic truth contained in the first of these two lines which is simply that in what we today would call a consensual relationship, nobody can 'have' or 'hold' the other person if they don't want to be in that relationship, but the second line then re-emphasises the stark contrast in status, where Shakespeare questions – possibly, when looked at objectively, with some reason – how he could even expect to be the recipient of such munificence as the young man through his wealth and status represents. |

|

The cause of this fair gift in me is wanting:

And so my patent back again is swerving. |

I lack any grounds or reasons for you to bestow such a great gift as yourself on me, and because of this, the 'patent' which entitled me to 'own' you now returns to you, the person who gave it to me in the first place.

|

|

Thy self thou gavest, thy own worth then not knowing,

Or me, to whom thou gavest it, else mistaking, |

You gave yourself to me being unaware of your own worth at the time, or else overestimating my worth when you did so...

This, in the line of argumentation pursued here, would make sense: if the young man thought at the time that Shakespeare was, if not in social status then in other ways his equal or at least of commensurate 'worth', then even being aware of his own status he might have chosen to 'give himself' to Will nonetheless. But Shakespeare now says that this assessment of their compatibility in 'worth' was wrong. And a minor but interesting detail: the Quarto Edition spells 'thy self' as two words, which is here retained. Most editors modernise this to one word, 'thyself', but this diminishes somewhat the gesture: saying to someone 'I gave myself to you', is strong but also quite commonplace; saying instead 'I gave my self to you' underlines the idea that I gave my whole being to you. Whether or not this is here intentional or simply an accident of typesetting we can't know, but I, as always, would err on the side of caution and allow for the possibility that it is pointed and deliberate, and what supports this possibility here in particular is the fact that Shakespeare does an unusual thing in the second half of this line. We would expect normally him to say: 'thy self thou gavest, thine own worth then not knowing,' but he doesn't, he says 'thy own', putting a second emphasis on the distinction between 'thy' and the word that follows. |

|

So thy great gift, upon misprision growing,

Comes home again on better judgement making. |

...and so your great gift, which came to me by mistake and there grew even further in value and worth – because you grew older and even more precious – now that you understand your own worth better and therefore are able to make a better judgment about it, comes back home to you: you are no longer mine, you have returned to yourself and to your own possession, so to speak.

|

|

Thus have I had thee as a dream doth flatter:

In sleep a king, but waking no such matter. |

And so I have owned and possessed you just in the way a dream flatters the dreamer: while I am asleep and in my dreams I can be a king, but once I wake up, I am no such thing.

This closing couplet is noteworthy for its double-edged meaning. The obvious and maybe primary conclusion is of course as just rendered: in my dreams I can be a king even though I am no such thing in reality, as I am made acutely aware the moment I wake up to be confronted with my everyday circumstance. But the line can also be read as in my illusional dreams you are a king, but once I wake up from this dream, this fantasy, I realise you to are no such matter, you are this very demanding, quite unfaithful and petulant and selfish young man that I have grown to love so much almost in spite of myself. And as on previous occasions – we noted it particularly in Sonnet 52 – the turn of phrase "Thus have I had thee" may well have some sexual connotations. Here they are not further supported and so this may not really apply on this occasion. On the other hand, we are talking about a lover saying to the man he loves, this seems to be the end, so it would make sense absolutely for this dimension, if it ever existed, to also be referenced. |

With its complete change in tone, Sonnet 87 ushers in a new and decidedly different phase in the relationship between William Shakespeare and his young lover. The sonnet draws on the vocabulary of law, ownership, and finance and in these largely factual terms Shakespeare appears to concede that the young man is simply out of his league: it is the most dejected and most resigned we have heard our poet in relation to the young man, and it marks the beginning of a long end to their extraordinary and extraordinarily complex connection.

Formally, the first immediately noteworthy detail about Sonnet 87 is that it is composed almost entirely of weak or 'feminine' rhymes resulting in lines with eleven rather than ten syllables. The only exception to this is the rhyme in lines two and four of the first quatrain: And like enough thou knowst thy estimate || My bonds in thee are all determinate."

As is the case so very often, we do not know whether Shakespeare does this deliberately to convey any particular message or meaning, but the only sonnet in the collection that uses exclusively feminine rhymes is Sonnet 20 which is in its entirety about the fact that the young man has all the good qualities of a woman, whilst being mercifully unencumbered by such bad ones as a woman may have. This certainly sounds like a coincidence too far: Shakespeare would have been cognisant of these two principal rhyme endings and their metaphorical associations with gender. And so that being the case, the assumption most likely has to be that here too he uses this softer, weaker rhyme scheme to draw our attention to itself.

The second formal aspect that is of great interest is the terminology: 'too dear', 'possessing', 'estimate', 'charter', 'worth', 'releasing', 'bonds', 'determinate' – we could be forgiven for thinking we're reading a lease agreement for a country estate including its furnishings and fittings, and that's just in the first quatrain. The second quatrain continues in a similar vein with 'patent' and 'worth' but rather augments these with 'riches' and 'fair gift', which suggest a dimension beyond that of an economic transaction at last, a sense that is then retained through the third quatrain, which reiterates the notion of the young man as a 'great gift' that he, the young man himself, has in the past offered to our poet.

If throughout the course of our 'reciting, revealing, and reliving' of William Shakespeare's Sonnets we received an idea that there is more to the relationship between these two men than meets the eye at several levels, both in the personal, intimate, physical domain, and also in the public, performative, economic domain, then Sonnet 87 does nothing to dispel this notion. It does the opposite. It weaves into itself those two domains and these various layers and makes it clear to anyone who is prepared to listen that this love is not just about passion, it is also about power, and it is about possession. And within this constellation, it isn't always entirely clear who's owning whom.

In terms of status, economic potency, and proximity to power there can be little doubt that it is the young aristocrat – and that he is an aristocrat of that we need no longer really be uncertain either – who has the upper hand. But we are called upon to remind ourselves with this sonnet that Shakespeare, submissive though he may show himself, and dejected though he may be, posits and positions himself as someone who has at least for some time and in some way 'had', 'held', even 'possessed' the young man. How much we want to read into this is perhaps today largely down to us, and I on this occasion more than on previous ones would counsel caution. It does this sonnet not strike me as one that draws on Shakespeare's saucy or suggestive register, at all. It sounds, if anything, remarkably sober, maybe actively, deliberately so. It is not playful and not witty. Not especially showy and not memorably melodious. It is, if anything, downcast and, a we ventured earlier, resigned.

And so the poem does pose the question, indirectly, but for this no less profoundly: what was it, really, that drew the young man to Shakespeare? Shakespeare is obviously being harsh on himself when he says that in him 'the cause of this fair gift' that is the young man is entirely wanting; and clearly we, from our perspective today, can think of a plethora of qualities and reasons that may have attracted the young man to Shakespeare. But how did the young man see himself at the time? How did he see Shakespeare? And how did this change over the course of the relationship? That it did change, we know for certain, and we also have been collective witness to some of the specific upheavals that occurred at various junctures, but with Sonnet 87 we may well wonder: what was it that made things exciting, thrilling at the beginning for the young man, and why has it gone stale?

An obvious answer, and one that offers itself from the ordering of the sonnets in the original Quarto Edition is of course that the arrival on the scene of the Rival Poet has driven a wedge between the young man and Shakespeare and that Shakespeare here now, after everything that has happened and been expressed in the Rival Poet sequence, effectively surrenders.

As we also saw though, some people – including my guests on this podcast, Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells – challenge the order of the sonnets in the original edition, even though they actually assume that the order was given the sonnets by Shakespeare himself, and they place the Rival Poet group of poems after this one. What we also heard though, from our most recent guest, Professor Gabriel Egan, is that Macdonald P Jackson, whom Edmondson Wells base their reordered edition on, makes a strong case only for the Sonnets numbered 104-126 to have been composed quite a bit later than had generally been assumed, while being much less certain about all the others. Always bearing in mind, of course, that we simply cannot be certain about anything, really, when it come to these sonnets.

I, as part of this episode on Sonnet 87, am not in a position to refute or endorse the findings of Macdonald P Jackson, but I shall endeavour to examine them in much more detail before we get to the end of the series. For the moment, suffice it for us to be aware that the order of the sonnets as we have it in the Quarto Edition has been questioned with varying degrees of assertiveness and similarly uneven evidential weight, and that therefore we cannot say the Rival Poet definitely has a role to play in the proceedings as they now ensue any more than we can say he definitely does not.

What we can say is that William Shakespeare's Sonnets were published in a numbered sequence – the fact alone that they are numbered turns them into a sequence by default – and that Sonnet 87 is the first sonnet to follow the Rival Poet group of poems, and it is this the point in the collection where William Shakespeare says to his young lover: all this has been like a dream to me, and in this dream I was a man who because of you would, just as I put it in my glorious Sonnet 29, "scorn to change my state with kings." But now, with this poem, I say 'farewell' to you. Because the reality is that I am not a king. And you are not a prince. I am a poet and you – whatever you truly are – you are out of my reach: I can keep you only if you want to be with me, and that – for whatever reason – is clearly no longer the case.

This, on its own, might be the end.

But of course it isn't. The finality and resignation of Sonnet 87 gets churned over and upended as soon as Sonnet 88, and with Sonnet 88 Shakespeare stages an inspired fightback for the love of his young man and indeed for the young man's character, so as not to say for the young man's soul...

Formally, the first immediately noteworthy detail about Sonnet 87 is that it is composed almost entirely of weak or 'feminine' rhymes resulting in lines with eleven rather than ten syllables. The only exception to this is the rhyme in lines two and four of the first quatrain: And like enough thou knowst thy estimate || My bonds in thee are all determinate."

As is the case so very often, we do not know whether Shakespeare does this deliberately to convey any particular message or meaning, but the only sonnet in the collection that uses exclusively feminine rhymes is Sonnet 20 which is in its entirety about the fact that the young man has all the good qualities of a woman, whilst being mercifully unencumbered by such bad ones as a woman may have. This certainly sounds like a coincidence too far: Shakespeare would have been cognisant of these two principal rhyme endings and their metaphorical associations with gender. And so that being the case, the assumption most likely has to be that here too he uses this softer, weaker rhyme scheme to draw our attention to itself.

The second formal aspect that is of great interest is the terminology: 'too dear', 'possessing', 'estimate', 'charter', 'worth', 'releasing', 'bonds', 'determinate' – we could be forgiven for thinking we're reading a lease agreement for a country estate including its furnishings and fittings, and that's just in the first quatrain. The second quatrain continues in a similar vein with 'patent' and 'worth' but rather augments these with 'riches' and 'fair gift', which suggest a dimension beyond that of an economic transaction at last, a sense that is then retained through the third quatrain, which reiterates the notion of the young man as a 'great gift' that he, the young man himself, has in the past offered to our poet.

If throughout the course of our 'reciting, revealing, and reliving' of William Shakespeare's Sonnets we received an idea that there is more to the relationship between these two men than meets the eye at several levels, both in the personal, intimate, physical domain, and also in the public, performative, economic domain, then Sonnet 87 does nothing to dispel this notion. It does the opposite. It weaves into itself those two domains and these various layers and makes it clear to anyone who is prepared to listen that this love is not just about passion, it is also about power, and it is about possession. And within this constellation, it isn't always entirely clear who's owning whom.

In terms of status, economic potency, and proximity to power there can be little doubt that it is the young aristocrat – and that he is an aristocrat of that we need no longer really be uncertain either – who has the upper hand. But we are called upon to remind ourselves with this sonnet that Shakespeare, submissive though he may show himself, and dejected though he may be, posits and positions himself as someone who has at least for some time and in some way 'had', 'held', even 'possessed' the young man. How much we want to read into this is perhaps today largely down to us, and I on this occasion more than on previous ones would counsel caution. It does this sonnet not strike me as one that draws on Shakespeare's saucy or suggestive register, at all. It sounds, if anything, remarkably sober, maybe actively, deliberately so. It is not playful and not witty. Not especially showy and not memorably melodious. It is, if anything, downcast and, a we ventured earlier, resigned.

And so the poem does pose the question, indirectly, but for this no less profoundly: what was it, really, that drew the young man to Shakespeare? Shakespeare is obviously being harsh on himself when he says that in him 'the cause of this fair gift' that is the young man is entirely wanting; and clearly we, from our perspective today, can think of a plethora of qualities and reasons that may have attracted the young man to Shakespeare. But how did the young man see himself at the time? How did he see Shakespeare? And how did this change over the course of the relationship? That it did change, we know for certain, and we also have been collective witness to some of the specific upheavals that occurred at various junctures, but with Sonnet 87 we may well wonder: what was it that made things exciting, thrilling at the beginning for the young man, and why has it gone stale?

An obvious answer, and one that offers itself from the ordering of the sonnets in the original Quarto Edition is of course that the arrival on the scene of the Rival Poet has driven a wedge between the young man and Shakespeare and that Shakespeare here now, after everything that has happened and been expressed in the Rival Poet sequence, effectively surrenders.

As we also saw though, some people – including my guests on this podcast, Paul Edmondson and Sir Stanley Wells – challenge the order of the sonnets in the original edition, even though they actually assume that the order was given the sonnets by Shakespeare himself, and they place the Rival Poet group of poems after this one. What we also heard though, from our most recent guest, Professor Gabriel Egan, is that Macdonald P Jackson, whom Edmondson Wells base their reordered edition on, makes a strong case only for the Sonnets numbered 104-126 to have been composed quite a bit later than had generally been assumed, while being much less certain about all the others. Always bearing in mind, of course, that we simply cannot be certain about anything, really, when it come to these sonnets.

I, as part of this episode on Sonnet 87, am not in a position to refute or endorse the findings of Macdonald P Jackson, but I shall endeavour to examine them in much more detail before we get to the end of the series. For the moment, suffice it for us to be aware that the order of the sonnets as we have it in the Quarto Edition has been questioned with varying degrees of assertiveness and similarly uneven evidential weight, and that therefore we cannot say the Rival Poet definitely has a role to play in the proceedings as they now ensue any more than we can say he definitely does not.

What we can say is that William Shakespeare's Sonnets were published in a numbered sequence – the fact alone that they are numbered turns them into a sequence by default – and that Sonnet 87 is the first sonnet to follow the Rival Poet group of poems, and it is this the point in the collection where William Shakespeare says to his young lover: all this has been like a dream to me, and in this dream I was a man who because of you would, just as I put it in my glorious Sonnet 29, "scorn to change my state with kings." But now, with this poem, I say 'farewell' to you. Because the reality is that I am not a king. And you are not a prince. I am a poet and you – whatever you truly are – you are out of my reach: I can keep you only if you want to be with me, and that – for whatever reason – is clearly no longer the case.

This, on its own, might be the end.

But of course it isn't. The finality and resignation of Sonnet 87 gets churned over and upended as soon as Sonnet 88, and with Sonnet 88 Shakespeare stages an inspired fightback for the love of his young man and indeed for the young man's character, so as not to say for the young man's soul...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!