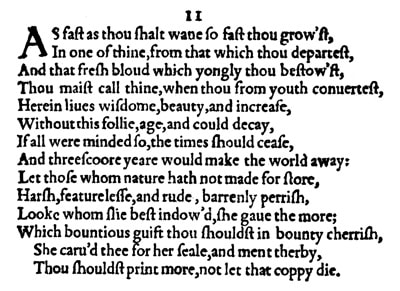

Sonnet 11: As Fast as Thou Shalt Wane, so Fast Thou Growst

|

As fast as thou shalt wane, so fast thou growst

In one of thine from that which thou departest, And that fresh blood, which youngly thou bestowst, Thou mayst call thine when thou from youth convertest. Herein lives wisdom, beauty, and increase; Without this, folly, age, and cold decay; If all were minded so, the times should cease And threescore year would make the world away. Let those whom Nature hath not made for store – Harsh, featureless, and rude – barrenly perish. Look whom she best endowed she gave the more, Which bounteous gift thou shouldst in bounty cherish. She carved thee for her seal and meant thereby Thou shouldst print more, not let that copy die. |

|

As fast as thou shalt wane, so fast thou growst

In one of thine from that which thou departest, |

As quickly as you are going to fade away through your advancing years when you depart from your own youth – "from that which thou departest" – so quickly will you grow in a child of yours...

|

|

And that fresh blood which youngly thou bestowst

Thou mayst call thine when thou from youth convertest. |

...and this child – "that fresh young blood" – which you in your youth give – bestow – to the world or indeed to a woman who will be the mother of that child, you may call yours even when you yourself change or turn away from your youth – "from youth convertest" – into an old man.

|

|

Herein lives wisdom, beauty, and increase

|

In this insight and, more to the point, in following it, lies wisdom, because it is the only sensible thing to do, beauty, because the child's beauty continues even when you lose yours, and increase, because by producing a child or preferably several, you grow your family, you generate a future for your name and your estate, and so you and the world will be roundly enriched...

|

|

Without this folly, age, and cold decay.

|

...whereas not following this insight is in itself foolish as it leaves you only with your old age and the cold decay that goes with it, leading up to and culminating in your death.

|

|

If all were minded so, the times should cease

|

If everybody thought as you do and refused to marry and have children, then time would come to an end...

|

|

And three score year would make the world away.

|

...and within sixty years – three score being three times twenty – the world would be gone. 'The world' here of course referring to the world of human beings: our species and with it therefore all civilisation.

|

|

Let those whom Nature hath not made for store –

|

Let those people whom Nature has not made to be preserved in their offspring and thus to live on...

|

|

Harsh, featureless, and rude – barrenly perish:

|

...– namely those who are harsh, featureless, and rude – die without having had children:

|

|

Look whom she best endowed she gave the more

|

Look how nature has given yet more to the person whom she had already given the most and best of everything – "whom she best endowed" – that person obviously being the young man who, we have so far mainly surmised, but who we will learn later with more certainty, is rich, powerful, intelligent and thus "best endowed." So in addition to all these gifts, nature has given him yet more....

|

|

Which bounteous gift thou shouldst in bounty cherish.

|

...and this bountiful gift you should enjoy and by implication share with equal generosity.

This is a theme that has come up several times now: that the beautiful man is the keeper of a loan, really; that this 'gift of nature' that he has received – his beauty – is only his to pass on. |

|

She carved thee for her seal and meant thereby

Thou shouldst print more, not let that copy die. |

A slightly abrupt change of metaphor here: she, Nature, cut you out to be a seal of herself – by implication her unparalleled beauty – so that you can print more iterations of yourself and not let the one version of that supreme beauty that currently exists, namely you, die with you when you reach the end of your life.

|

The refreshingly blunt and remarkably utilitarian Sonnet 11 makes a now well established old argument with a couple of surprising new twists and confirms or at least supports a couple of observations about Shakespeare's day and about the young man that we made before.

The first quatrain really doesn't tell us anything we didn't already know, and that the young man has not heard literally ten times before: you will grow old and then die, in the process losing your beauty, and the way to give a continuation of yourself to yourself and to the world is by producing a child whom, as you turn away from your own youth and towards your old age, you will be able to watch grow up. And this son's beauty – we are always talking about a boy here in the context of this young man's child – will then by extension be yours, because he is, after all, your son and receives his beauty from you.

Then a confident assertion that what I, the poet, here am saying is wisdom which, if followed, leads to further beauty and wealth, whereas continuing to ignore the counsel here given would be a foolish course of action leading to nothing more than your decline and then death.

From our perspective today the first genuinely interesting note is struck in the next couple of lines where William Shakespeare tells the young man that if everybody behaved as he does and failed to produce children, then "the times should cease:" history would end, "and threescore year would make the world away:" after sixty years there would be nobody left. This is of course a reference to the three score year and ten – 70 years – that we know from the Bible and that is meant to be the lifespan of a human being. But in Sonnet 2 we noted how comparatively few people actually attain that full life expectancy, and how quickly you age in Shakespeare's day:

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty's field

We saw there that as far as Shakespeare is concerned, 40 is old. Sonnet 11 seems to confirm this and even go a step further: if, after sixty years of no children being produced, the world of humans has gone or nearly gone, then that means that nobody or hardly anybody will be left after sixty years. Certainly not enough of us to repopulate the world. Obviously, this being a rhetorical as well as poetic piece of writing, we should be wary of taking it too literally, but it is nevertheless telling that this is put so categorically here. And it may also once again be a deliberate mild exaggeration. Which points to a new tonality we already found traces of in Sonnet 8 and which now comes through even stronger.

Because next come the first two lines in the whole sequence so far that we today would most likely consider to be humorous, when Shakespeare effectively sets up a joke with a punchline built into it: "Let those whom nature hath not made for store" – let the people who really aren't made by nature to go on living beyond their own days, he suggests, wedging in the deadpan definition of these people: "Harsh, featureless, and rude," let them die without producing any offspring, but not you, who are given everything by nature, including your beauty, and who are therefore clearly intended for creating offspring and with it a continuation of yourself.

Whether Shakespeare means this to be read as funny, or whether he means it seriously we don't know of course. But across his whole body of writing, he over and over again proves himself to be profoundly embracing of human nature. He gives some of his greatest, most interesting, most compelling, most complex storylines and speeches to characters who are fundamentally flawed, who are in turns and at times, if rarely in that sense featureless, then certainly harsh and rude. So Shakespeare hardly dismisses them or denies them their right to exist, quite the opposite. Which then would seem to suggest that here he may well be aiming for some levity.

This is in itself extremely interesting. With Sonnet 8 we started to wonder whether Shakespeare's heart is still truly and entirely in this task of convincing the young man that he should produce a child. With Sonnet 9 we felt he might be getting quite daring in his tone with the young man, and in Sonnet 10 he broke the barrier between himself and the recipient of the poem by either putting himself directly in it or assuming the mantle of the person on whose behalf he possibly might be writing, thus indirectly putting himself in it. Could it be that Shakespeare is now starting to have fun with this whole thing? That he is signalling – almost 'yet again', after what went in Sonnet 8 – that all this really doesn't need to be taken all that seriously?

What would slightly lend support to this supposition is the surprisingly abrupt deployment of a brand new but somewhat messy metaphor – unprimed, unexplained, so as not to say unwarranted – in the closing couplet. It seems to come out of nowhere and it appears hastily assembled, because it doesn't stack up properly: even allowing for the fact that the word 'copy' in Shakespeare has a looser meaning of 'type' or 'iteration' than strictly a direct facsimile of an original, it still craves our indulgence rather to hear the young man described as both the carved seal – the original form from which imprints are made – and the printed product, the 'copy' which he should not 'let die', by failing to make further copies of himself.

So Sonnet 11 is nothing if not intriguing. It is both bold and brazen, constructed and careless, hyperbolic and borderline hilarious. And it sets us up for some big changes in tone and dynamics imminently....

The first quatrain really doesn't tell us anything we didn't already know, and that the young man has not heard literally ten times before: you will grow old and then die, in the process losing your beauty, and the way to give a continuation of yourself to yourself and to the world is by producing a child whom, as you turn away from your own youth and towards your old age, you will be able to watch grow up. And this son's beauty – we are always talking about a boy here in the context of this young man's child – will then by extension be yours, because he is, after all, your son and receives his beauty from you.

Then a confident assertion that what I, the poet, here am saying is wisdom which, if followed, leads to further beauty and wealth, whereas continuing to ignore the counsel here given would be a foolish course of action leading to nothing more than your decline and then death.

From our perspective today the first genuinely interesting note is struck in the next couple of lines where William Shakespeare tells the young man that if everybody behaved as he does and failed to produce children, then "the times should cease:" history would end, "and threescore year would make the world away:" after sixty years there would be nobody left. This is of course a reference to the three score year and ten – 70 years – that we know from the Bible and that is meant to be the lifespan of a human being. But in Sonnet 2 we noted how comparatively few people actually attain that full life expectancy, and how quickly you age in Shakespeare's day:

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty's field

We saw there that as far as Shakespeare is concerned, 40 is old. Sonnet 11 seems to confirm this and even go a step further: if, after sixty years of no children being produced, the world of humans has gone or nearly gone, then that means that nobody or hardly anybody will be left after sixty years. Certainly not enough of us to repopulate the world. Obviously, this being a rhetorical as well as poetic piece of writing, we should be wary of taking it too literally, but it is nevertheless telling that this is put so categorically here. And it may also once again be a deliberate mild exaggeration. Which points to a new tonality we already found traces of in Sonnet 8 and which now comes through even stronger.

Because next come the first two lines in the whole sequence so far that we today would most likely consider to be humorous, when Shakespeare effectively sets up a joke with a punchline built into it: "Let those whom nature hath not made for store" – let the people who really aren't made by nature to go on living beyond their own days, he suggests, wedging in the deadpan definition of these people: "Harsh, featureless, and rude," let them die without producing any offspring, but not you, who are given everything by nature, including your beauty, and who are therefore clearly intended for creating offspring and with it a continuation of yourself.

Whether Shakespeare means this to be read as funny, or whether he means it seriously we don't know of course. But across his whole body of writing, he over and over again proves himself to be profoundly embracing of human nature. He gives some of his greatest, most interesting, most compelling, most complex storylines and speeches to characters who are fundamentally flawed, who are in turns and at times, if rarely in that sense featureless, then certainly harsh and rude. So Shakespeare hardly dismisses them or denies them their right to exist, quite the opposite. Which then would seem to suggest that here he may well be aiming for some levity.

This is in itself extremely interesting. With Sonnet 8 we started to wonder whether Shakespeare's heart is still truly and entirely in this task of convincing the young man that he should produce a child. With Sonnet 9 we felt he might be getting quite daring in his tone with the young man, and in Sonnet 10 he broke the barrier between himself and the recipient of the poem by either putting himself directly in it or assuming the mantle of the person on whose behalf he possibly might be writing, thus indirectly putting himself in it. Could it be that Shakespeare is now starting to have fun with this whole thing? That he is signalling – almost 'yet again', after what went in Sonnet 8 – that all this really doesn't need to be taken all that seriously?

What would slightly lend support to this supposition is the surprisingly abrupt deployment of a brand new but somewhat messy metaphor – unprimed, unexplained, so as not to say unwarranted – in the closing couplet. It seems to come out of nowhere and it appears hastily assembled, because it doesn't stack up properly: even allowing for the fact that the word 'copy' in Shakespeare has a looser meaning of 'type' or 'iteration' than strictly a direct facsimile of an original, it still craves our indulgence rather to hear the young man described as both the carved seal – the original form from which imprints are made – and the printed product, the 'copy' which he should not 'let die', by failing to make further copies of himself.

So Sonnet 11 is nothing if not intriguing. It is both bold and brazen, constructed and careless, hyperbolic and borderline hilarious. And it sets us up for some big changes in tone and dynamics imminently....

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!