Sonnet 45: The Other Two, Slight Air and Purging Fire

|

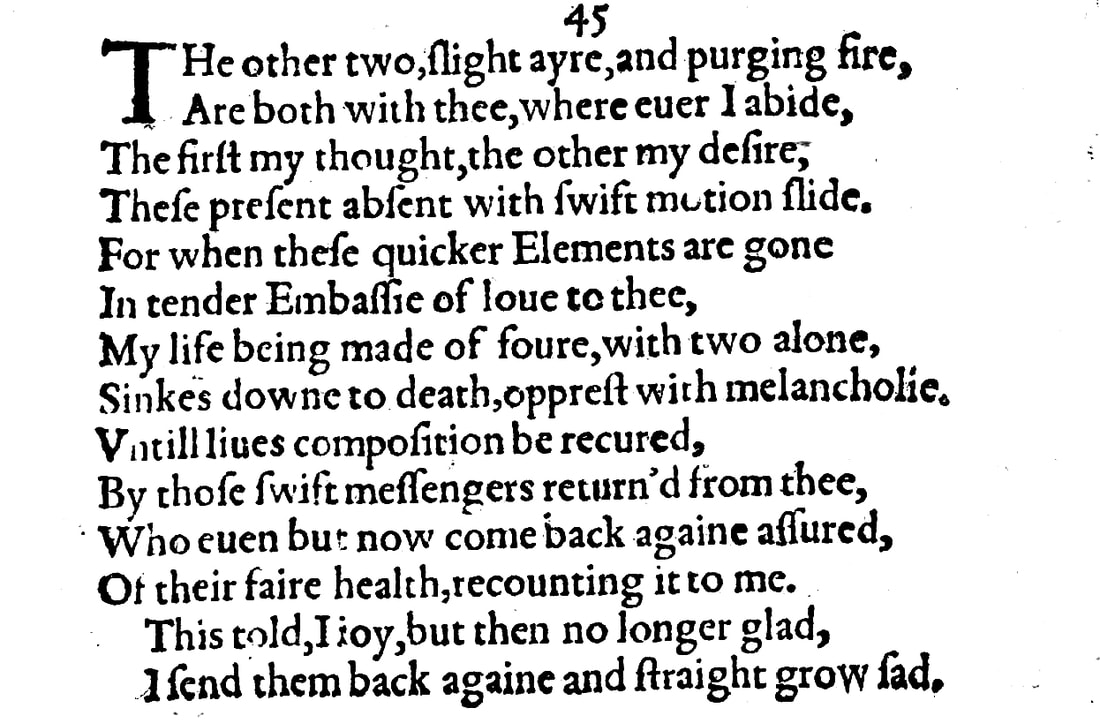

The other two, slight air and purging fire,

Are both with thee, wherever I abide; The first, my thought, the other, my desire, These present-absent with swift motion slide, For when these quicker elements are gone In tender embassy of love to thee, My life, being made of four, with two alone Sinks down to earth, oppressed with melancholy, Until life's composition be recured By those swift messengers returned from thee Who even but now come back again, assured Of thy fair health, recounting it to me. This told, I joy, but then, no longer glad, I send them back again and straight grow sad. |

|

The other two, slight air and purging fire,

|

The sonnet continues seamlessly from the previous one and still talks about elements, so:

The other two elements, namely air which is 'slight' because it has no substantive body and no perceptible weight, and fire, which is purging because it in a biblical sense and also in a literal sense purifies... |

|

Are still with thee, wherever I abide;

|

...both these elements are always with you, no matter where I happen to be.

|

|

The first my thought, the other my desire,

|

The first of these, air, equates to my thought, and the other, fire, is my desire for you...

These associations are fairly commonplace and would not have surprised anyone who read or heard this sonnet, but it is telling that Shakespeare here spells out a desire for the young man, which further supports the strong impression we have been getting that this relationship has since ceased to be a purely Platonic friendship. |

|

These present-absent with swift motion slide,

|

...these two elements are so insubstantial that they can constantly slide to and fro between here where I am and there where you are, making it feel as if they were in both places at once.

|

|

For when these quicker elements are gone

In tender embassy of love to thee, |

And here is the reason why they are so constantly moving backwards and forwards: because when these elements, which are much quicker than the heavy, slow elements of the previous poem, water and earth, have gone to you in their role as emissaries from me, conveying my love and passion for you like an ambassador who might bear epistles of love or indeed sonnets to the betrothed of a king or a queen, for example...

|

|

My life, being made of four, with two alone

Sinks down to earth, oppressed with melancholy, |

...then my life, which, like everybody else's is made up of all four elements to function properly, now being left with only the two – and the two heavy ones at that – sinks down to the ground in a profound depression...

Note that 'melancholy' here is pronounced as three syllables in order to scan. |

|

Until life's composition be recured,

|

...and this lasts until my life is restored to its complete composition, consisting of all four elements...

|

|

By those swift messengers returned from thee,

Who even but now come back again, assured Of thy fair health, recounting it to me. |

...when these two light elements, which are both acting as swift messengers, return to me from you in an instant, and they do so assured of your good health and relate this to me.

The Quarto Edition has 'their' fair health, which editors in the main agree must be a common 'thy'/'their' confusion by the typesetter. |

|

This told I joy, but then, no longer glad,

I sent them back again and straight grow sad. |

Told this good news, I rejoice, but then – implied is in almost the exact same instant again – I am no longer glad, presumably because I am after all away from you and miss you and would much rather you were here with me than just having to cling on to the 'messages' brought to me by my thoughts and my desire, and so I send them back to you again, and of course, thus imbalanced, become sad again straight away.

|

Sonnet 45 follows on directly from Sonnet 44 as a seamless continuation and therefore needs to be read in tandem with it for it to make sense. With Sonnet 44 having introduced the two classical elements earth and water and explained how it is their heavy materiality that prevents William Shakespeare from being with his young lover, Sonnet 45 now speaks to the nature of the remaining two elements, air and fire, and finds a way to express how it is that even though they be physically insubstantial and infused with liveliness, they still contribute to his prevailing sadness about this period of separation:

If the dull substance of my flesh were thought,

Injurious distance should not stop my way,

For then, despite of space, I would be brought

From limits far remote where thou dost stay.

No matter then although my foot did stand

Upon the farthest earth removed from thee,

For nimble thought can jump both see and land

As soon as think the place where he would be.

But ah, thought kills me that I am not thought

To leap large lengths of miles when thou art gone,

But that, so much of earth and water wrought,

I must attend time's leisure with my moan,

Receiving naught by elements so slow

But heavy tears, badges of either's woe.

The other two, slight air and purging fire,

Are both with thee, wherever I abide;

The first, my thought, the other, my desire,

These present-absent with swift motion slide,

For when these quicker elements are gone

In tender embassy of love to thee,

My life, being made of four, with two alone

Sinks down to earth, oppressed with melancholy,

Until life's composition be recured

By those swift messengers returned from thee

Who even but now come back again, assured

Of thy fair health, recounting it to me.

This told, I joy, but then, no longer glad,

I send them back again and straight grow sad.

While Sonnet 44 set up a simple premise that was so easy to follow, we ventured that it might be bordering on the banal, Sonnet 45 ups the ante considerably on the theoretical, if not indeed the emotional level. As we have sensed on several occasions before, the logic at work is not of Boolean rigour, but then George Boole was born a good 250 years after Shakespeare, so it would be unreasonable to expect otherwise.

The essence of these two sonnets is the idea that while my body, being made of heavy substances, principally earth – for which today we would read minerals and carbon, and water, which is indeed what the human body consists of to roughly 60 percent – cannot cover the physical distance between us when I am away from you, my thought and my desire for you, being made of air and fire respectively, are always with you. Today, we would not consider air to be insubstantial since we understand its chemical composition, and we certainly wouldn't consider fire to be an element, but rather a process, but in Shakespeare's Renaissance understanding of the world, the notion that air and fire, like earth and water, are of a comparable kind and that they are both insubstantial and therefore free from the physical constraints that heavy elements are subject to is common currency.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect to Sonnet 45 is that Shakespeare doesn't leave it at that: he could have argued, had he wanted to, I am made of water and earth and therefore have to remain here where I am, but my thoughts and my desire are made of air and fire and they can and will therefore always be with you. End of story: his audience – whoever that may have been for this sonnet, whether he in fact sent it to his lover, or kept it to read it to him later, or never intended it for anyone's eyes and ears but his own – would have understood this and happily accepted that the love he bears his young man causes his thoughts and his desire to be entirely with him.

Instead though Shakespeare picks up on the classical notion that in order for the human being to be complete, these four elements have to remain in a finely tuned balance. And so if I send these two elements of me, my thoughts and my desire, to you across a distance, then I lack them: my composition goes out of kilter and I am weighed down by the watery earthiness of my sluggish body without the force of air and fire enlivening and lifting it. Thought and desire therefore are not with you permanently and still, they oscillate between me, where I need them to keep me going, and you, where I send them to relate my love to you and to receive news and reassurance of your wellbeing in return, and so I myself am torn between the sadness I feel for being away from you and the joy I get from thinking of you.

And so while Sonnet 45 may not be logically absolutely sound and the physics to us seem quaint, its psychology is deeply insightful: our period of separation causes me both hope and despair, both uncertainty and self-propelled reassurance; in the absence of any effective communication from you I hold on to my hope that all is well since no news is – we cling on to this rail for our own sanity – good news.

That there is no effective communication is something the words of these two sonnets don't spell out but that we can both infer and reasonably assume. Having done so before and very recently, I need not rehearse the modes and channels of communication that are open to us but not to Shakespeare and his young man, and so suffice it to say that nothing in Sonnets 43 through 51 suggests that Shakespeare has had any kind of response, missive or message from his young man. This does not prove that there was none, but we don't need to stray far into the domain of conjecture here to think it entirely possible that indeed, there wasn't: Shakespeare finds ways to let us know when he is in an active two-way exchange or composing poetry directly after one, but here, over a longish stretch of sonnets and therefore we must assume time, this doesn't apply.

And this may tell us two things that are certainly of great interest and that, as it happens, fit our broad picture of Shakespeare's situation and the trajectory of his relationship with this young man plausibly well. Assuming, as we believe we have reason to do and as – we noted not so long ago – even people who reorder the sonnets tend to allow, that this sequence is more or less in the correct order and further assuming that the 'correct' order is determined by chronologically sequential events, then what we observe is this:

– Awakening love and unabashed declaration of such with some setbacks and possibly a rebuke: Sonnets 18 to 26.

– Separation through absence from my young lover: 27 & 28.

– Joyous reunion followed by abject disorientation, anger, sadness and forgiveness all resulting from betrayal, interspersed with a couple of sonnets that may or may not belong in the sequence but that in any case bring no new event into the proceedings: 33 to 42 (38 and 39 being the 'rogues').

– Renewed and extended separation through absence, reflecting an ennui and longing or, as we have termed it, boredom and limbo: 43 to 51.

If this is more or less what has happened then – and this is the second thing that would match up with what we have gathered so far – the fact that during this second period of separation, Shakespeare receives no further word from his young man, would appear to be rather in character. His fickleness has been established, as has his need, on occasion, to assert his independence and to do whatever the hell he likes. These two sonnets say nothing about this, but they are part of an effective bridge that is being cast to the moment when Shakespeare literally spells it out.

Sonnets 44 and 45 sit near the beginning of this separation, and while we don't know what causes it or how long it is – other than that reasonable spacing of these sonnets over time would suggest weeks rather than days – what we do know is that it is bookended by Shakespeare's express forgiveness of the young man's transgression in Sonnets 40 to 42, and what sounds like a both boisterously celebratory and serenely sensual reunion in 52, 53, and that would allow us to speculate – it remains, it has to be said, pure speculation, albeit informed by what we can read in and between and throughout these lines – that following turmoil, Shakespeare finds himself away worrying, wishing, and wondering, without any kind of affirmation that the love is kept alive at his lover's end as well as his, before finally finding it fulsomely so.

We are here in danger of getting carried away and somewhat ahead of ourselves though, because what follows next is another pair of sonnets that extend this excursion into more abstract reflections on the challenges imposed by love at a distance with the carefully constructed and also quite classically cushioned Sonnets 46 & 47.

If the dull substance of my flesh were thought,

Injurious distance should not stop my way,

For then, despite of space, I would be brought

From limits far remote where thou dost stay.

No matter then although my foot did stand

Upon the farthest earth removed from thee,

For nimble thought can jump both see and land

As soon as think the place where he would be.

But ah, thought kills me that I am not thought

To leap large lengths of miles when thou art gone,

But that, so much of earth and water wrought,

I must attend time's leisure with my moan,

Receiving naught by elements so slow

But heavy tears, badges of either's woe.

The other two, slight air and purging fire,

Are both with thee, wherever I abide;

The first, my thought, the other, my desire,

These present-absent with swift motion slide,

For when these quicker elements are gone

In tender embassy of love to thee,

My life, being made of four, with two alone

Sinks down to earth, oppressed with melancholy,

Until life's composition be recured

By those swift messengers returned from thee

Who even but now come back again, assured

Of thy fair health, recounting it to me.

This told, I joy, but then, no longer glad,

I send them back again and straight grow sad.

While Sonnet 44 set up a simple premise that was so easy to follow, we ventured that it might be bordering on the banal, Sonnet 45 ups the ante considerably on the theoretical, if not indeed the emotional level. As we have sensed on several occasions before, the logic at work is not of Boolean rigour, but then George Boole was born a good 250 years after Shakespeare, so it would be unreasonable to expect otherwise.

The essence of these two sonnets is the idea that while my body, being made of heavy substances, principally earth – for which today we would read minerals and carbon, and water, which is indeed what the human body consists of to roughly 60 percent – cannot cover the physical distance between us when I am away from you, my thought and my desire for you, being made of air and fire respectively, are always with you. Today, we would not consider air to be insubstantial since we understand its chemical composition, and we certainly wouldn't consider fire to be an element, but rather a process, but in Shakespeare's Renaissance understanding of the world, the notion that air and fire, like earth and water, are of a comparable kind and that they are both insubstantial and therefore free from the physical constraints that heavy elements are subject to is common currency.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect to Sonnet 45 is that Shakespeare doesn't leave it at that: he could have argued, had he wanted to, I am made of water and earth and therefore have to remain here where I am, but my thoughts and my desire are made of air and fire and they can and will therefore always be with you. End of story: his audience – whoever that may have been for this sonnet, whether he in fact sent it to his lover, or kept it to read it to him later, or never intended it for anyone's eyes and ears but his own – would have understood this and happily accepted that the love he bears his young man causes his thoughts and his desire to be entirely with him.

Instead though Shakespeare picks up on the classical notion that in order for the human being to be complete, these four elements have to remain in a finely tuned balance. And so if I send these two elements of me, my thoughts and my desire, to you across a distance, then I lack them: my composition goes out of kilter and I am weighed down by the watery earthiness of my sluggish body without the force of air and fire enlivening and lifting it. Thought and desire therefore are not with you permanently and still, they oscillate between me, where I need them to keep me going, and you, where I send them to relate my love to you and to receive news and reassurance of your wellbeing in return, and so I myself am torn between the sadness I feel for being away from you and the joy I get from thinking of you.

And so while Sonnet 45 may not be logically absolutely sound and the physics to us seem quaint, its psychology is deeply insightful: our period of separation causes me both hope and despair, both uncertainty and self-propelled reassurance; in the absence of any effective communication from you I hold on to my hope that all is well since no news is – we cling on to this rail for our own sanity – good news.

That there is no effective communication is something the words of these two sonnets don't spell out but that we can both infer and reasonably assume. Having done so before and very recently, I need not rehearse the modes and channels of communication that are open to us but not to Shakespeare and his young man, and so suffice it to say that nothing in Sonnets 43 through 51 suggests that Shakespeare has had any kind of response, missive or message from his young man. This does not prove that there was none, but we don't need to stray far into the domain of conjecture here to think it entirely possible that indeed, there wasn't: Shakespeare finds ways to let us know when he is in an active two-way exchange or composing poetry directly after one, but here, over a longish stretch of sonnets and therefore we must assume time, this doesn't apply.

And this may tell us two things that are certainly of great interest and that, as it happens, fit our broad picture of Shakespeare's situation and the trajectory of his relationship with this young man plausibly well. Assuming, as we believe we have reason to do and as – we noted not so long ago – even people who reorder the sonnets tend to allow, that this sequence is more or less in the correct order and further assuming that the 'correct' order is determined by chronologically sequential events, then what we observe is this:

– Awakening love and unabashed declaration of such with some setbacks and possibly a rebuke: Sonnets 18 to 26.

– Separation through absence from my young lover: 27 & 28.

– Joyous reunion followed by abject disorientation, anger, sadness and forgiveness all resulting from betrayal, interspersed with a couple of sonnets that may or may not belong in the sequence but that in any case bring no new event into the proceedings: 33 to 42 (38 and 39 being the 'rogues').

– Renewed and extended separation through absence, reflecting an ennui and longing or, as we have termed it, boredom and limbo: 43 to 51.

If this is more or less what has happened then – and this is the second thing that would match up with what we have gathered so far – the fact that during this second period of separation, Shakespeare receives no further word from his young man, would appear to be rather in character. His fickleness has been established, as has his need, on occasion, to assert his independence and to do whatever the hell he likes. These two sonnets say nothing about this, but they are part of an effective bridge that is being cast to the moment when Shakespeare literally spells it out.

Sonnets 44 and 45 sit near the beginning of this separation, and while we don't know what causes it or how long it is – other than that reasonable spacing of these sonnets over time would suggest weeks rather than days – what we do know is that it is bookended by Shakespeare's express forgiveness of the young man's transgression in Sonnets 40 to 42, and what sounds like a both boisterously celebratory and serenely sensual reunion in 52, 53, and that would allow us to speculate – it remains, it has to be said, pure speculation, albeit informed by what we can read in and between and throughout these lines – that following turmoil, Shakespeare finds himself away worrying, wishing, and wondering, without any kind of affirmation that the love is kept alive at his lover's end as well as his, before finally finding it fulsomely so.

We are here in danger of getting carried away and somewhat ahead of ourselves though, because what follows next is another pair of sonnets that extend this excursion into more abstract reflections on the challenges imposed by love at a distance with the carefully constructed and also quite classically cushioned Sonnets 46 & 47.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!