Sonnet 20: A Woman's Face, With Nature's Own Hand Painted

|

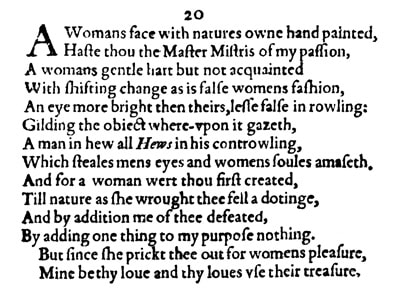

A woman's face, with Nature's own hand painted,

Hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion; A woman's gentle heart, but not acquainted With shifting change, as is false women's fashion; An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling, Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth, A man in hue all hues in his controlling, Which steals men's eyes and women's souls amazeth. And for a woman wert thou first created, Till Nature, as she wrought thee, fell a-doting, And by addition me of thee defeated, By adding one thing to my purpose nothing. But since she pricked thee out for women's pleasure Mine be thy love, and thy love's use their treasure. |

|

A woman's face, with Nature's own hand painted,

Hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion; |

You, who are the master-mistress of my passion have the face of a woman, painted by Nature herself, meaning that it is a face of natural beauty, as opposed to one that is 'painted' with make-up. Shakespeare repeatedly in his writing shows a considerable degree of disdain towards women who wear make-up, and the implied contrast here between the young man's natural beauty and a woman's unnatural, and therefore fake appearance is clearly deliberate in view of what follows.

The 1609 Quarto Edition does not capitalise 'Nature', but nature being personified here and referred to later, it may make sense to do so. |

|

A woman's gentle heart, but not acquainted

With shifting change as is false women's fashion; |

You also have the gentle heart of a woman, but unlike a woman's heart, yours is not used to or familiar with the unreliability and mood swings that is the fashion of false women.

'Fashion' most likely here is intended to mean 'general way' or 'typical modus' rather than 'contemporary style', and whether Shakespeare means to say that this lack of dependability is the way of false women only, or that of all women whom he is calling generally false, we don't know. Clearly though, he does not hold these women whom he is talking about in terribly high esteem. |

|

An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling,

|

Your eyes are brighter than those of women, and again less false because they don't roll like those of women who use their eyes to fake interest or emotional engagement, to seduce or beguile dishonestly...

|

|

Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth;

|

...and in fact what your eyes do is gild everything they look on, meaning they make whatever you look on shine more preciously and beautifully.

|

|

A man in hue all hues in his controlling

|

You are a man whose appearance – hue – controls or dominates and therefore exceeds in quality the appearance of all other appearances...

|

|

Which steals men's eyes and women's souls amazeth.

|

...to the extent where you attract the attention of other men and capture the heart and soul of women. 'Amaze' in Shakespeare can have a meaning more generally of 'overwhelm' or 'captivate' than simply today's 'astonish'.

|

|

And for a woman wert thou first created,

|

The line can be read in two ways, which is most likely deliberate. Either: 'and you were first created for a woman', meaning that as a man you would ordinarily be created for a wife; or: 'and you were first created as a woman', meaning that Nature, who created you, started out making you as a woman.

The way the poem continues seems to favour the latter interpretation, though the ending then gives as much value to the former, and again this double layering is very likely entirely Shakespeare's intention. |

|

Till Nature, as she wrought thee, fell a-doting,

|

Until Nature, as she was making you, started doting on you, and falling in love with you, most likely because you turned out so lovely...

|

|

And by addition me of thee defeated,

|

Again, a fairly obvious and successful double meaning: if we read the line above as you were created by Nature for a woman, then this can be read as, in addition to that woman, for whom you were intended, Nature also defeated me by making me fall in love with you; if we read the line above as Nature started out creating you as a woman, then we can read this line to mean, and by an act of addition she defeated me in any attempt I might have made in loving this woman who was about to be made, in the following way:

|

|

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

|

By adding something to you that has no purpose to me.

And again, this line would seem to support the interpretation above that goes: Nature, while she was making you as a woman, fell in love with you and defeated me by adding something to you that is of no use to me. Knowing Shakespeare though, he would probably be happiest for us to read the two meanings concurrently and delight in the dexterity of his wordplay. |

|

But since she pricked thee out for women's pleasure

|

But since she, Nature, marked you out – and, with a pun most pointedly intended – equipped you with a prick to pleasure women...

|

|

Mine be thy love, and thy love's use their treasure.

|

...let me have your love, and let the practical use or physical application of that love – namely sex – belong to women.

|

The fabulously frank and somewhat saucy Sonnet 20 takes the proverbial bull by the horn and leads it straight to the elephant in the room, addressing head on the fact that the person I, the poet, am here in love with is a young man; and it confirms one of the principal clues we were given earlier as to the young man's identity, which together make this one of the most important sonnets for our understanding of The Fair Youth and Shakespeare's relationship with him.

In Sonnet 20, William Shakespeare tells the young man that he looks like a woman. He then makes a few comparisons between the young man and women generally, which come across as borderline disparaging about certainly a certain type of woman, and then follows this with a fairly categorical statement about the current nature of the relationship between him and the young man: since Nature has equipped you with one thing that is of no use to me – your prick – I claim for myself your love, while women can have the 'use' of your love, which to all intents and purposes means sex with you.

Going by this sonnet then, and at this point in the relationship, we can say with the degree of certainty that we can say anything about these sonnets, which is defined by what the words themselves tell us, that the person Shakespeare has fallen in love with or is at any rate declaring a passion for, is, for him, of the 'wrong' gender and that therefore their relationship at this point is an explicitly non-sexual one.

Much has been said and indeed argued about whether or not this is the case: whether or not the love that Shakespeare so openly celebrates for his young male lover should be understood as a sexual one or a purely 'Platonic' one, and if we continue – as we have been doing – to listen to the words and what they tell us, then we can answer this question, at least for the time being, quite emphatically and clearly: he himself, William Shakespeare tells the young man and in doing so us, that he has no use for the man's sex, that he wants his love only.

Whether or not this stays that way remains to be seen, and we don't need to anticipate this here, because there will be one or two twists and turns in the relationship before it becomes truly relevant. What we do want to have a look at though here are two observations that are in one case certainly interesting and in the other surely significant.

The first one is William Shakespeare's characterisation here of the women he is referring to. I am being careful – you may notice – not to talk about 'Shakespeare's attitude to women' generally, because these are two quite categorically different things. Shakespeare has written in his plays some of the most powerful, faceted, intelligent, and rounded female characters ever created by any author, so it would be simplistic in the extreme, and also unjust, to draw any conclusions about Shakespeare's relationship with and to women generally from the way he talks about women in this particular sonnet. That said, the way he talks about women in this particular sonnet is really not overly flattering: twice he uses the adjective 'false', and he isn't at all clear whether he wants us here to think only of some women as false and these false women being prone to shifting change and the ostentatious rolling of eyes, or whether he wants us to think of all women as at least potentially false and behaving in such reprehensible fashion.

What we can tell is that Shakespeare has an appreciable degree of disdain for inauthenticity. This comes up again in these sonnets and it comes up elsewhere in his writing: he is not fond of heavy make-up and of mannered conduct. Where this stems from we don't know and it may not be particularly fruitful at this point to speculate; but we get a fairly unequivocal idea that Shakespeare is – if that's not too strong a word to use here – conflicted in his perception of the kind of woman he is referring to: he speaks admiringly of "a woman's gentle heart" but expresses unease about women's perceived or experienced lack of trustworthiness and steadfastness, and there is at the very least some level of generalisation at work here.

The second observation, and the one that is of much greater specific relevance to our interest in the sonnets and the young man at this particular juncture is the fact in and of itself that Shakespeare puts it to the young man and in doing so allows us to know: this person is a man who looks to all intents an purposes like a woman.

This is far from usual: not every young man looks like a woman. Granted, we are in an era when women's roles on stage are played by men, and so gender fluidity is alive and well four hundred plus years ago: people, it is probably fair to say, may have been a great deal less worked up and far less categorical in their understanding and appreciation of sex and gender than we might think or even than we in certain contexts are ourselves. But it is still the case – and very much so – that this is a patriarchal society in which a man of importance must produce a male heir, and in which a woman is legally the possession of her father first and then her husband. So to tell a young man that he has a woman's face is rather out of the ordinary.

William Shakespeare, and this is not an overstatement, values truthfulness and truth. His characters in his plays are to this day being brought to life in every language spoken on earth because they are so true to human nature. When he disparages falseness then we are allowed to believe him: it's a theme that runs through his work and it certainly props up throughout these sonnets. So Shakespeare saying to the young man that he looks like a woman is something we can take literally, and as information. And it is entirely congruent with everything we've heard so far. The repeated extolling of the young man's beauty above all else, not his strength, his valour, his fortitude, his sparring or his horse riding, his beauty is celebrated throughout the entire Procreation Sequence, the first 17 Sonnets of the collection. "Thou art thy mother's glass:" we noted with Sonnet 3 how specific and also unusual it is for a poet to tell a young man that he looks like his mother. Not his father, his mother.

We have enumerated on by now numerous occasions the characteristics these sonnets themselves tell us to look for in any search for the individual they are addressed to and we went as far in our Special Edition on the Procreation Sonnets to name one particular candidate who is not alone in potentially satisfying some of them but who, as far as we can tell, is alone in meeting all of them so far, and this Sonnet 20 now adds one more weight onto these scales in favour of that particular candidate, whom – with all the caveats and disclaimers contained in the episode on the Procreation Sonnets – we may again here name: Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton. We will dedicate an entire episode to The Fair Youth and so this here is not the point to argue that The Fair Youth is or is not Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton. But if you employ your favourite search engine and ask to see a portrait of this particular young English nobleman, attributed to the painter John de Critz, you will be presented with a picture of a young man who looks just like a girl. There is no other way of putting it. In today's language you could ask: 'what is that supposed to mean? What does a "girl" look like anyway?' But in the context of William Shakespeare's day, this is one fine young man who looks like a young woman and so we have one more indication that is of great importance and use to us.

And it is not even just the specific individual. Yes in the portrait by John de Critz, Henry Wriothesley does look like a young woman and he does also bear a striking resemblance to his mother, Mary Wriothesley. But this sonnet does not tell us who the young man is. It tells us what the young man looks like. And there is at least one – there may well be several others – but there is at least one young man who at the time of William Shakespeare matches the description, and so we have yet more reason to accept that these sonnets are written directly to and for a real living human being, not for some abstract notion of beauty or for some idealised figure, or for some purely poetic purpose or endeavour.

What Sonnet 20 does – first and foremost – is confirm what we've been sensing all along, that our poet, William Shakespeare, finds himself – to his own great perplexity and possibly even vexation – enamoured of a young man who just happens to be feminine in his appearance. And in doing so, this sonnet – much as Sonnet 19 did – also underpins our notion of a trajectory and a continuation: it, too, fits in the sequence, it too makes sense, it too is clearly and credibly addressed to the same young man as all the ones that have gone before so far. And it is not in the least bit coy about the reality this presents him with.

How Shakespeare deals with this, and how this forever fascinating relationship now evolves, that is going to be very much the subject of these next ensuing sonnets...

In Sonnet 20, William Shakespeare tells the young man that he looks like a woman. He then makes a few comparisons between the young man and women generally, which come across as borderline disparaging about certainly a certain type of woman, and then follows this with a fairly categorical statement about the current nature of the relationship between him and the young man: since Nature has equipped you with one thing that is of no use to me – your prick – I claim for myself your love, while women can have the 'use' of your love, which to all intents and purposes means sex with you.

Going by this sonnet then, and at this point in the relationship, we can say with the degree of certainty that we can say anything about these sonnets, which is defined by what the words themselves tell us, that the person Shakespeare has fallen in love with or is at any rate declaring a passion for, is, for him, of the 'wrong' gender and that therefore their relationship at this point is an explicitly non-sexual one.

Much has been said and indeed argued about whether or not this is the case: whether or not the love that Shakespeare so openly celebrates for his young male lover should be understood as a sexual one or a purely 'Platonic' one, and if we continue – as we have been doing – to listen to the words and what they tell us, then we can answer this question, at least for the time being, quite emphatically and clearly: he himself, William Shakespeare tells the young man and in doing so us, that he has no use for the man's sex, that he wants his love only.

Whether or not this stays that way remains to be seen, and we don't need to anticipate this here, because there will be one or two twists and turns in the relationship before it becomes truly relevant. What we do want to have a look at though here are two observations that are in one case certainly interesting and in the other surely significant.

The first one is William Shakespeare's characterisation here of the women he is referring to. I am being careful – you may notice – not to talk about 'Shakespeare's attitude to women' generally, because these are two quite categorically different things. Shakespeare has written in his plays some of the most powerful, faceted, intelligent, and rounded female characters ever created by any author, so it would be simplistic in the extreme, and also unjust, to draw any conclusions about Shakespeare's relationship with and to women generally from the way he talks about women in this particular sonnet. That said, the way he talks about women in this particular sonnet is really not overly flattering: twice he uses the adjective 'false', and he isn't at all clear whether he wants us here to think only of some women as false and these false women being prone to shifting change and the ostentatious rolling of eyes, or whether he wants us to think of all women as at least potentially false and behaving in such reprehensible fashion.

What we can tell is that Shakespeare has an appreciable degree of disdain for inauthenticity. This comes up again in these sonnets and it comes up elsewhere in his writing: he is not fond of heavy make-up and of mannered conduct. Where this stems from we don't know and it may not be particularly fruitful at this point to speculate; but we get a fairly unequivocal idea that Shakespeare is – if that's not too strong a word to use here – conflicted in his perception of the kind of woman he is referring to: he speaks admiringly of "a woman's gentle heart" but expresses unease about women's perceived or experienced lack of trustworthiness and steadfastness, and there is at the very least some level of generalisation at work here.

The second observation, and the one that is of much greater specific relevance to our interest in the sonnets and the young man at this particular juncture is the fact in and of itself that Shakespeare puts it to the young man and in doing so allows us to know: this person is a man who looks to all intents an purposes like a woman.

This is far from usual: not every young man looks like a woman. Granted, we are in an era when women's roles on stage are played by men, and so gender fluidity is alive and well four hundred plus years ago: people, it is probably fair to say, may have been a great deal less worked up and far less categorical in their understanding and appreciation of sex and gender than we might think or even than we in certain contexts are ourselves. But it is still the case – and very much so – that this is a patriarchal society in which a man of importance must produce a male heir, and in which a woman is legally the possession of her father first and then her husband. So to tell a young man that he has a woman's face is rather out of the ordinary.

William Shakespeare, and this is not an overstatement, values truthfulness and truth. His characters in his plays are to this day being brought to life in every language spoken on earth because they are so true to human nature. When he disparages falseness then we are allowed to believe him: it's a theme that runs through his work and it certainly props up throughout these sonnets. So Shakespeare saying to the young man that he looks like a woman is something we can take literally, and as information. And it is entirely congruent with everything we've heard so far. The repeated extolling of the young man's beauty above all else, not his strength, his valour, his fortitude, his sparring or his horse riding, his beauty is celebrated throughout the entire Procreation Sequence, the first 17 Sonnets of the collection. "Thou art thy mother's glass:" we noted with Sonnet 3 how specific and also unusual it is for a poet to tell a young man that he looks like his mother. Not his father, his mother.

We have enumerated on by now numerous occasions the characteristics these sonnets themselves tell us to look for in any search for the individual they are addressed to and we went as far in our Special Edition on the Procreation Sonnets to name one particular candidate who is not alone in potentially satisfying some of them but who, as far as we can tell, is alone in meeting all of them so far, and this Sonnet 20 now adds one more weight onto these scales in favour of that particular candidate, whom – with all the caveats and disclaimers contained in the episode on the Procreation Sonnets – we may again here name: Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton. We will dedicate an entire episode to The Fair Youth and so this here is not the point to argue that The Fair Youth is or is not Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton. But if you employ your favourite search engine and ask to see a portrait of this particular young English nobleman, attributed to the painter John de Critz, you will be presented with a picture of a young man who looks just like a girl. There is no other way of putting it. In today's language you could ask: 'what is that supposed to mean? What does a "girl" look like anyway?' But in the context of William Shakespeare's day, this is one fine young man who looks like a young woman and so we have one more indication that is of great importance and use to us.

And it is not even just the specific individual. Yes in the portrait by John de Critz, Henry Wriothesley does look like a young woman and he does also bear a striking resemblance to his mother, Mary Wriothesley. But this sonnet does not tell us who the young man is. It tells us what the young man looks like. And there is at least one – there may well be several others – but there is at least one young man who at the time of William Shakespeare matches the description, and so we have yet more reason to accept that these sonnets are written directly to and for a real living human being, not for some abstract notion of beauty or for some idealised figure, or for some purely poetic purpose or endeavour.

What Sonnet 20 does – first and foremost – is confirm what we've been sensing all along, that our poet, William Shakespeare, finds himself – to his own great perplexity and possibly even vexation – enamoured of a young man who just happens to be feminine in his appearance. And in doing so, this sonnet – much as Sonnet 19 did – also underpins our notion of a trajectory and a continuation: it, too, fits in the sequence, it too makes sense, it too is clearly and credibly addressed to the same young man as all the ones that have gone before so far. And it is not in the least bit coy about the reality this presents him with.

How Shakespeare deals with this, and how this forever fascinating relationship now evolves, that is going to be very much the subject of these next ensuing sonnets...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!