Sonnet 70: That Thou Are Blamed Shall Not Be Thy Defect

|

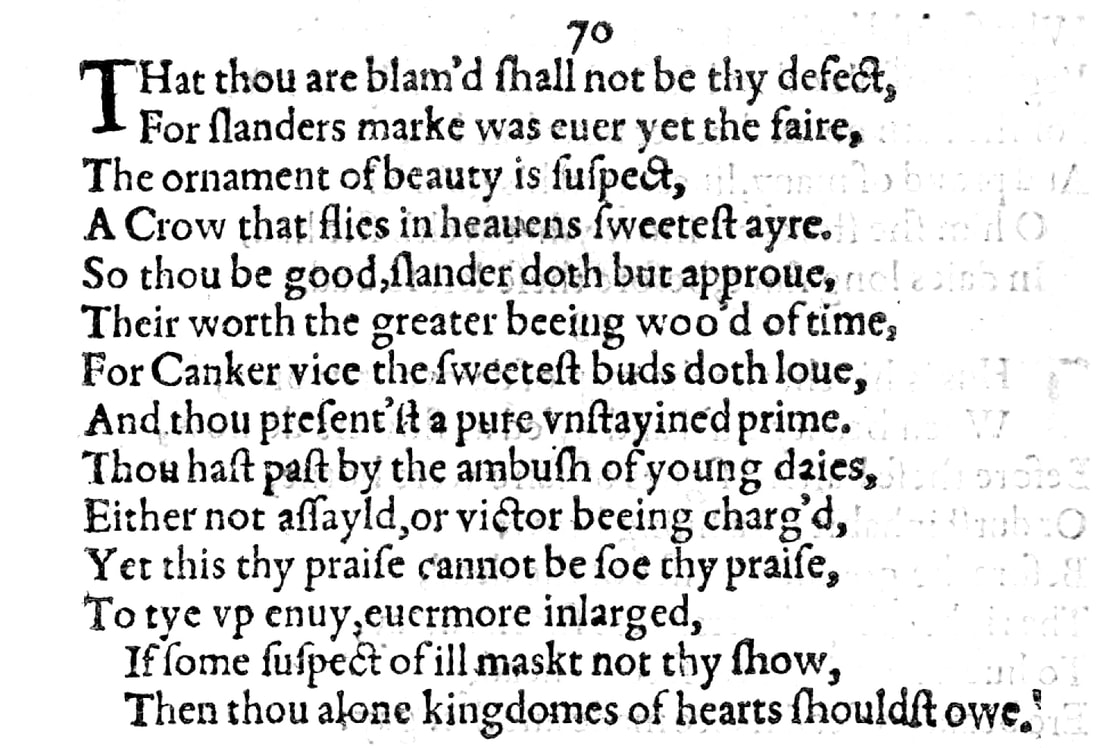

That thou are blamed shall not be thy defect,

For slander's mark was ever yet the fair: The ornament of beauty is suspect, A crow that flies in heaven's sweetest air. So thou be good, slander doth but approve Thy worth the greater, being wooed of time, For canker vice the sweetest buds doth love, And thou presentst a pure, unstained prime. Thou hast passed by the ambush of young days, Either not assailed or victor being charged, Yet this, thy praise, cannot be so thy praise To tie up envy, evermore enlarged. If some suspect of ill masked not thy show Then thou alone kingdoms of hearts shouldst owe. |

|

That thou are blamed shall not be thy defect,

|

That you are blamed shall not be considered to be your fault.

The sonnet seems to connect with and refer directly to the previous sonnet, in which Shakespeare told his young lover that the reason why he is getting a bad reputation is that his behaviour appears to show that he is growing 'common'. This sonnet now in contrast sets out to make it clear from the very start that, actually, none of this is the young man's fault. A very minor but – if like me you are genuinely riveted by linguistic detail and love the fine points of grammar – fascinating textual issue lies in the little and ostensibly simple word 'are'. Most editors simply 'correct' this, as they see it, to 'art', so in most renderings of the sonnet, you will read: That thou art blamed shall not be thy defect, And at first glance there seems to be nothing wrong with that. After all, the 'correct' conjugation for the informal form of address 'thou' is, indeed, 'art', and so it would appear that editors are merely doing our Will a favour by putting right something that either he or his typesetter clearly got wrong. Except it is not that simple nor is it anywhere near as straightforward: Because Shakespeare does use the form 'are' with 'thou' on several occasions. Not many, it has to be said, but where he does, he seems to do it when, and therefore possibly because, the word is followed by another consonant. In any case, it would appear that in some instances Shakespeare chooses to use 'are' with 'thou' for euphony: in order to get a more pleasing sound. And so for us, this creates a dilemma: should we assume that somebody – either Shakespeare himself or the typesetter working from his manuscript – got this wrong and printed 'are' when really Shakespeare fully intended it to be 'art'? It is entirely possible: it's an easy mistake to make and the Quarto Edition is littered with similar seemingly minor mistakes. But what if Shakespeare didn't make a mistake? What if he wrote down on his page 'are' and the typesetter here diligently reproduced exactly what he saw? What, indeed, if the typesetter felt minded to correct Shakespeare and Shakespeare flung his arms in the air in horror and exclaimed: no! thou shalt not mess with my poetry, peasant! We don't know. And so as a writer, my instinct is to go with what we have and assume nothing, certainly not that something which may or may not be a mistake is a mistake, simply because it suits our simplistic interpretation of a rulebook which we are in any case no longer all that familiar with, since we have long since ceased conjugating our verbs in this way. And of course in Sonnet 47, where we in fact very briefly touched on the same issue before, Shakespeare says – and this you will usually find honoured in editions of The Sonnets: So either by thy picture or my love, Thyself away are present still with me, For thou not farther than my thoughts canst move And I am still with them and they with thee |

|

For slander's mark was ever yet the fair:

|

Because the mark – as in the ugly stain – of slander has always been on those who are beautiful.

This is a remarkably compact line where for our understanding there is at least an 'upon' missing: we would expect something like: 'For slander's mark was ever yet upon the fair', but Shakespeare here takes this as read simply so the line scans and retains its near-perfect iambic pentameter. (It is only near-perfect because the prosody, certainly for our ears today, is slightly hampered by 'ever'. |

|

The ornament of beauty is suspect,

A crow that flies in heaven's sweetest air. |

The ornament of beauty is suspicion, and that suspicion is like a black, potentially portentous bird that darkens even the most beautiful sky merely by its presence. The crow at least since Roman times has been considered a bird of bad omen and so if crows start invading your summery sunny sky then that is perceived as bad news indeed...

Puzzling to us is the use of 'suspect' as a noun: we are tempted to read the sentence as, 'the ornament that is beauty is suspect to us', and that would even make some degree of sense, because we could then say: well, a beautiful person who is like an ornament to a setting or a group of people, is somewhat suspect because we can't trust their beauty entirely, and that circumstance then would be the metaphorical crow that flies even in the sweetest air. And perhaps Shakespeare enjoys this secondary reading and invites us to allow it too, but certainly the primary meaning is that beauty is 'adorned', somewhat perversely or ironically, with suspicion. And 'suspect' here, as indeed 'defect' above, are both stressed on the second syllable, not as we would do if they were adjectives, on the first. |

|

So thou be good, slander doth but approve

Thy worth the greater, being wooed of time, |

And so although you may be good, the slander which settles upon you does in fact only serve to make your high worth and great qualities stand out even more, and these qualities are being wooed of time, meaning that they outlive and overcome time, they are wooed away from the ever-entropic force of time which ultimately destroys everything and reduces all to nothing, except you, as I, the poet, have told you many times before and will gladly tell you again in due course.

The Quarto Edition here has 'Their worth', but since there is no plural that this could refer to, it is generally accepted to be a very common their/thy confusion and therefore gets emended. |

|

For canker vice the sweetest buds doth love,

And thou presentst a pure, unstained prime. |

Because – and this now referring again to the sad fact of life that slander attaches itself to everything and everyone that is beautiful – the canker worm, which as a parasitic infestation on flowers damages and ruins them, is drawn to the sweetest, for which again as so often read prettiest, most beautiful, most delightful flower buds, and you happen to come along as a pure and unstained prime of life: a youth untainted by sin or scandal..

This, as well as the following two lines, directly contradicts what was said in Sonnet 69, where the young man's actions caused him to acquire the 'rank smell of weeds', and we will look into what the significance of this is in a moment, of course. |

|

Thou hast passed by the ambush of young days,

Either not assailed or victor being charged, |

You have passed by – as in missed out on or deliberately avoided – the usual assault of youthful folly and frolicking, either because you were not ever the target of any such 'attack' on your angelic innocence, or because you conquered it, by holding on steadfastly to your unshakeable integrity.

In light of what we know about the young man, this is plain nonsense, unless of course Shakespeare is either a) talking to somebody else entirely, which in light of Sonnet 69 is improbable, or b) he is being facetious, or c) there is something else going on here, which we shall need to further examine... For the line to scan and to fit into the uninterrupted pattern of strong or 'male' ten-syllable endings, either the 'Either' or the 'assailed' here has to be pronounced with one syllable. Either: Ei'r not assailed or victor being charged or Either not 'sailed or victor being charged Considering that 'either' is such a common and 'assailed' a rather less common word, and bearing in mind what we know of Shakespeare's dialect, which tends to be quite a touch rounder and more gravelly than how we speak to today, my hunch is that the most likely intention is for the line to be read: Ei'r not assailed or victor being charged |

|

Yet this, thy praise, cannot be so thy praise

To tie up envy, ever more enlarged. |

But this praise of you cannot be left to stand, because it would or indeed does attract and bind to itself the envy of others which simply grows, the more you are praised.

Editors also point to the late Middle English meaning of 'to set free' for 'enlarge', and it does seem very likely that Shakespeare is at least punning on this, since he gives us the idea of envy being tied up and then forever newly set free. |

|

If some suspect of ill masked not thy show

Then thou alone kingdoms of hearts shouldst owe. |

If there were not some suspicion of wrongdoing about you, if people didn't find it necessary to put on you this stain of slander, then you alone would be able to own the kingdom of all hearts, meaning everybody would simply have to love and adore you and nobody else.

Note that here, as in the famous Sonnet 18, 'owe' means 'own'. |

With Sonnet 70, William Shakespeare once more performs the poetic equivalent of a handbrake turn and swivels what we thought we could understand from Sonnet 69 around 180 degrees to race headlong in the opposite direction. The charge levied against his young lover – that with his conduct he has been allowing himself to become 'common' and thus acquire a reputation way beneath his supposedly exalted status – is here lifted, and any such insinuation summarily dismissed as slander, prompting us primarily to wonder: why? What is causing the accusations against the young man in the first place and what then brings about this virtuoso ventriloquy?

And that Sonnet 70 is in fact Shakespeare's own response to Sonnet 69 and comes paired with it, is in itself – although apparently obvious – not beyond any doubt, though whether any doubt could be found to be reasonable is something we'll also want to consider carefully.

Here are the two poems – as we believe intended – back to back:

Those parts of thee that the world's eye doth view

Want nothing that the thought of hearts can mend;

All tongues, the voice of souls, give thee that due,

Uttering bare truth, even so as foes commend.

Thy outward thus with outward praise is crowned,

But those same tongues that give thee so thine own

In other accents do this praise confound

By seeing farther than the eye hath shown:

They look into the beauty of thy mind,

And that, in guess, they measure by thy deeds,

Then, churls, their thoughts, although their eyes were kind,

To thy fair flower add the rank smell of weeds.

But why thy odour matcheth not thy show,

The soil is this: that thou dost common grow.

That thou are blamed shall not be thy defect,

For slander's mark was ever yet the fair:

The ornament of beauty is suspect,

A crow that flies in heaven's sweetest air.

So thou be good, slander doth but approve

Thy worth the greater, being wooed of time,

For canker vice the sweetest buds doth love,

And thou presentst a pure, unstained prime.

Thou hast passed by the ambush of young days,

Either not assailed or victor being charged,

Yet this, thy praise, cannot be so thy praise

To tie up envy, evermore enlarged.

If some suspect of ill masked not thy show

Then thou alone kingdoms of hearts shouldst owe.

First, then, to the question on which hinge the others: is this a pair of sonnets that belong together? As flagged up a moment ago: it could be put forward that we have no proof of this. Many, though again by no means all, sonnets that follow a previous one as a direct continuation start with a conjunction, a word like 'but' or 'and' or 'so', making it clear that the argument continues.

Sonnet 70 does not do this, it starts with a new sentence that could quite conceivably stand on its own. In fact, the entire sonnet could stand on its own, as could Sonnet 69, and so our – it has to be said widely accepted – contention that these two form a strongly tied pair stems from two simple factors:

First, Sonnet 69 talks about wagging tongues spreading a bad metaphorical smell about the young man, which in all but name is slander and Sonnet 70 immediately picks this up and removes the guilt for such slander from the recipient of the sonnet. That this should apply to both this sonnet and the previous one seems obvious.

Second, the two sonnets follow each other in the collection. The collection, although it may not be strictly in sequence, is very clearly organised, and sonnets that belong together have deliberately been placed with each other by what Edmondson Wells, you may remember, not only called an ordering mind, but the ordering mind of Shakespeare himself. Whether or not the latter is the case we can't possibly know, let alone know for certain, but that the former applies is also obvious.

On the balance of probabilities then – and although there is as so often no absolute proof – we can be fairly certain that yes, these two poems form a pair, with Sonnet 70 continuing the argument of Sonnet 69.

If that is the case, then the whole construction of this couple of sonnets is astonishing, for exactly the reasons we mentioned and to some extent discussed in the previous episode. Here is what Will is saying to his young man:

- You are outwardly perfect.

This is not news to us.

- Everybody recognises this and says so.

Neither is this, really: we early on got the impression that this young man is generally admired for his looks.

- But: the same people who admire your beauty and say so also now look at what you are up to and they disapprove of this and disparage your name.

Even this does not come as a huge surprise: we know at least part of what the young man has been up to and we saw Shakespeare's understandably troubled reaction to this on two previous occasions – specifically the crisis from Sonnet 33 intermittently to Sonnet 42, and then again to some extent in Sonnets 57 & 58 – and so the fact that the world is beginning to talk also can hardly amaze.

By this point in the proceedings we are led to believe that what people say about the young man is true and Shakespeare risks leaving it at that. But then he continues:

- Look, it's not your fault that you attract such a bad press, everybody who is beautiful does: people are envious and so the better you behave, the more people talk, spreading rumours about you, because if that weren't the case then you alone would be king of all love and adoration.

Which doesn't actually strictly follow: it is not actually the logical consequence that the young man would in this way, if there were no slander upon him, be the only person that is lovable in the world, it is a poetic Shakespearean non-sequitur. But that is almost by the by because as we have seen before, logic is not William Shakespeare's strongest suit.

There are two possible reasons why a poet might write in two such distinct and independently viewable parts. Either because that's what was always his intention: Shakespeare frequently spreads an argument or a theme over two sonnets, sometimes more, so why not here? It's not entirely unlike starting a birthday card on the left hand page because you know from the outset that you are going to cover two pages; and there is almost no reason to assume that this here isn't the case. Except that there is also the possibility that there was a comeback to Sonnet 69 from the young man to which this Sonnet 70 is in turn the response.

On one or two occasions previously have we aired the possibility that these sonnets form part of an informal exchange, either accompanying, or acting as, letters. Sonnet 26 very clearly is either conceived as a letter or sent along with one, since it actually states, "To thee I send this written embassage," and there have been one or two other instances when we thought there was a distinct possibility that a sonnet came in response to a response from the young man. Sonnet 58 to 57 in fact sound a bit like that, although there, as here, it is just as imaginable that Shakespeare composed both poems from the outset, almost conducting something of an internal dialogue with his young lover.

So what is the answer? We must acknowledge, we have no idea. We are really entirely in the realm of conjecture from here on in, but for me, who I constantly see these people in their to us so familiar and yet at the same time so alien existence, it is more than a little attractive to imagine the young, impetuous, even at times petulant nobleman reading or hearing Sonnet 69 and storming into Will's study, shoving a piece of parchment or paper in the poet's face and demanding to know what he means by this. In fact, Shakespeare may, for all we know, have voiced in his inimitable fashion signals he's picked up from the grapevine with good intentions: who's to say that he's not meaning to alert the young man, knowing he has at least some of his ear some of the time. And then, once so confronted, in kicks the retreat to appease his lover, to not risk losing him? And we really do need to phrase this as a question, because it is only one of a million different possible scenarios.

That Shakespeare does not want to lose his lover hardly needs speculating or explaining. Whether for purely emotional, personal reasons, or, as we think may quite possibly also be the case, for professional reasons too, you do not want your young, beautiful, rich, influential lover to be angry with you for long. And just to briefly recap, in case you wonder: I don't think we need to doubt greatly that we are dealing with the same young man, Shakespeare's young lover, 'The Fair Youth'. Why? Because Sonnet 70 – as we just saw – is almost certainly the direct continuation of Sonnet 69. If it is, then it by necessity has to be addressed to the same person. Sonnet 69, as we also saw, fits the profile of the young man to the extent that we know him perfectly, and so, seeing there is no other good reason to assume otherwise, other than the radical change in tone and direction, we probably really don't need to look further.

But how radical is this change in tone really? In Sonnet 69, Shakespeare refers to the people spreading gossip about the young man, or possibly to their thoughts, as 'churls'. Whether it is the people or their thoughts, the implication is the same: he uses a mild term of admonishment that in other instances he has deployed tenderly, even lovingly, to chide the people who are harming the young man's reputation. It's not dissimilar to us using a word like 'rascals'. It hardly implies moral outrage at damned lies being disseminated. It is, in other words, mildly ironic.

And then, in Sonnet 70, Shakespeare goes over the top with his characterisation of the young man as 'pure', untainted, unassailed by the dangers and temptations that come with young age. Knowing everything we know about this young man and his conduct in relation to Shakespeare and Shakespeare's mistress so far, and the anxieties and anguish this has caused him, that is plainly ridiculous. Shakespeare is either teasing his young man, or his is playing to his vanity, or he is being so supremely disingenuous that we have to wonder is he pulling someone's leg.

And it is really this total incredulity instilled in us by the sonnet that makes me favour the idea that Shakespeare might be responding to a response. That he once again overstepped a mark with his verse and is trying, by the same means, to make amends. The truth though is that you will have to either draw your own conclusions, or leave this conundrum, like so many others, unresolved, because Shakespeare himself does not provide anything that could be considered conclusive.

With Sonnets 69 & 70, the group of Sonnets 61 to 70 comes to an end and with Sonnet 71, a new phase begins that does not explore entirely new themes – mortality, the passing of time, the love for the young man all remain present – but they reach a new depth and with it a new sincerity, before, at the midpoint with Sonnet 77, yet again everything changes...

And that Sonnet 70 is in fact Shakespeare's own response to Sonnet 69 and comes paired with it, is in itself – although apparently obvious – not beyond any doubt, though whether any doubt could be found to be reasonable is something we'll also want to consider carefully.

Here are the two poems – as we believe intended – back to back:

Those parts of thee that the world's eye doth view

Want nothing that the thought of hearts can mend;

All tongues, the voice of souls, give thee that due,

Uttering bare truth, even so as foes commend.

Thy outward thus with outward praise is crowned,

But those same tongues that give thee so thine own

In other accents do this praise confound

By seeing farther than the eye hath shown:

They look into the beauty of thy mind,

And that, in guess, they measure by thy deeds,

Then, churls, their thoughts, although their eyes were kind,

To thy fair flower add the rank smell of weeds.

But why thy odour matcheth not thy show,

The soil is this: that thou dost common grow.

That thou are blamed shall not be thy defect,

For slander's mark was ever yet the fair:

The ornament of beauty is suspect,

A crow that flies in heaven's sweetest air.

So thou be good, slander doth but approve

Thy worth the greater, being wooed of time,

For canker vice the sweetest buds doth love,

And thou presentst a pure, unstained prime.

Thou hast passed by the ambush of young days,

Either not assailed or victor being charged,

Yet this, thy praise, cannot be so thy praise

To tie up envy, evermore enlarged.

If some suspect of ill masked not thy show

Then thou alone kingdoms of hearts shouldst owe.

First, then, to the question on which hinge the others: is this a pair of sonnets that belong together? As flagged up a moment ago: it could be put forward that we have no proof of this. Many, though again by no means all, sonnets that follow a previous one as a direct continuation start with a conjunction, a word like 'but' or 'and' or 'so', making it clear that the argument continues.

Sonnet 70 does not do this, it starts with a new sentence that could quite conceivably stand on its own. In fact, the entire sonnet could stand on its own, as could Sonnet 69, and so our – it has to be said widely accepted – contention that these two form a strongly tied pair stems from two simple factors:

First, Sonnet 69 talks about wagging tongues spreading a bad metaphorical smell about the young man, which in all but name is slander and Sonnet 70 immediately picks this up and removes the guilt for such slander from the recipient of the sonnet. That this should apply to both this sonnet and the previous one seems obvious.

Second, the two sonnets follow each other in the collection. The collection, although it may not be strictly in sequence, is very clearly organised, and sonnets that belong together have deliberately been placed with each other by what Edmondson Wells, you may remember, not only called an ordering mind, but the ordering mind of Shakespeare himself. Whether or not the latter is the case we can't possibly know, let alone know for certain, but that the former applies is also obvious.

On the balance of probabilities then – and although there is as so often no absolute proof – we can be fairly certain that yes, these two poems form a pair, with Sonnet 70 continuing the argument of Sonnet 69.

If that is the case, then the whole construction of this couple of sonnets is astonishing, for exactly the reasons we mentioned and to some extent discussed in the previous episode. Here is what Will is saying to his young man:

- You are outwardly perfect.

This is not news to us.

- Everybody recognises this and says so.

Neither is this, really: we early on got the impression that this young man is generally admired for his looks.

- But: the same people who admire your beauty and say so also now look at what you are up to and they disapprove of this and disparage your name.

Even this does not come as a huge surprise: we know at least part of what the young man has been up to and we saw Shakespeare's understandably troubled reaction to this on two previous occasions – specifically the crisis from Sonnet 33 intermittently to Sonnet 42, and then again to some extent in Sonnets 57 & 58 – and so the fact that the world is beginning to talk also can hardly amaze.

By this point in the proceedings we are led to believe that what people say about the young man is true and Shakespeare risks leaving it at that. But then he continues:

- Look, it's not your fault that you attract such a bad press, everybody who is beautiful does: people are envious and so the better you behave, the more people talk, spreading rumours about you, because if that weren't the case then you alone would be king of all love and adoration.

Which doesn't actually strictly follow: it is not actually the logical consequence that the young man would in this way, if there were no slander upon him, be the only person that is lovable in the world, it is a poetic Shakespearean non-sequitur. But that is almost by the by because as we have seen before, logic is not William Shakespeare's strongest suit.

There are two possible reasons why a poet might write in two such distinct and independently viewable parts. Either because that's what was always his intention: Shakespeare frequently spreads an argument or a theme over two sonnets, sometimes more, so why not here? It's not entirely unlike starting a birthday card on the left hand page because you know from the outset that you are going to cover two pages; and there is almost no reason to assume that this here isn't the case. Except that there is also the possibility that there was a comeback to Sonnet 69 from the young man to which this Sonnet 70 is in turn the response.

On one or two occasions previously have we aired the possibility that these sonnets form part of an informal exchange, either accompanying, or acting as, letters. Sonnet 26 very clearly is either conceived as a letter or sent along with one, since it actually states, "To thee I send this written embassage," and there have been one or two other instances when we thought there was a distinct possibility that a sonnet came in response to a response from the young man. Sonnet 58 to 57 in fact sound a bit like that, although there, as here, it is just as imaginable that Shakespeare composed both poems from the outset, almost conducting something of an internal dialogue with his young lover.

So what is the answer? We must acknowledge, we have no idea. We are really entirely in the realm of conjecture from here on in, but for me, who I constantly see these people in their to us so familiar and yet at the same time so alien existence, it is more than a little attractive to imagine the young, impetuous, even at times petulant nobleman reading or hearing Sonnet 69 and storming into Will's study, shoving a piece of parchment or paper in the poet's face and demanding to know what he means by this. In fact, Shakespeare may, for all we know, have voiced in his inimitable fashion signals he's picked up from the grapevine with good intentions: who's to say that he's not meaning to alert the young man, knowing he has at least some of his ear some of the time. And then, once so confronted, in kicks the retreat to appease his lover, to not risk losing him? And we really do need to phrase this as a question, because it is only one of a million different possible scenarios.

That Shakespeare does not want to lose his lover hardly needs speculating or explaining. Whether for purely emotional, personal reasons, or, as we think may quite possibly also be the case, for professional reasons too, you do not want your young, beautiful, rich, influential lover to be angry with you for long. And just to briefly recap, in case you wonder: I don't think we need to doubt greatly that we are dealing with the same young man, Shakespeare's young lover, 'The Fair Youth'. Why? Because Sonnet 70 – as we just saw – is almost certainly the direct continuation of Sonnet 69. If it is, then it by necessity has to be addressed to the same person. Sonnet 69, as we also saw, fits the profile of the young man to the extent that we know him perfectly, and so, seeing there is no other good reason to assume otherwise, other than the radical change in tone and direction, we probably really don't need to look further.

But how radical is this change in tone really? In Sonnet 69, Shakespeare refers to the people spreading gossip about the young man, or possibly to their thoughts, as 'churls'. Whether it is the people or their thoughts, the implication is the same: he uses a mild term of admonishment that in other instances he has deployed tenderly, even lovingly, to chide the people who are harming the young man's reputation. It's not dissimilar to us using a word like 'rascals'. It hardly implies moral outrage at damned lies being disseminated. It is, in other words, mildly ironic.

And then, in Sonnet 70, Shakespeare goes over the top with his characterisation of the young man as 'pure', untainted, unassailed by the dangers and temptations that come with young age. Knowing everything we know about this young man and his conduct in relation to Shakespeare and Shakespeare's mistress so far, and the anxieties and anguish this has caused him, that is plainly ridiculous. Shakespeare is either teasing his young man, or his is playing to his vanity, or he is being so supremely disingenuous that we have to wonder is he pulling someone's leg.

And it is really this total incredulity instilled in us by the sonnet that makes me favour the idea that Shakespeare might be responding to a response. That he once again overstepped a mark with his verse and is trying, by the same means, to make amends. The truth though is that you will have to either draw your own conclusions, or leave this conundrum, like so many others, unresolved, because Shakespeare himself does not provide anything that could be considered conclusive.

With Sonnets 69 & 70, the group of Sonnets 61 to 70 comes to an end and with Sonnet 71, a new phase begins that does not explore entirely new themes – mortality, the passing of time, the love for the young man all remain present – but they reach a new depth and with it a new sincerity, before, at the midpoint with Sonnet 77, yet again everything changes...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!