Sonnet 22: My Glass Shall Not Persuade Me I Am Old

|

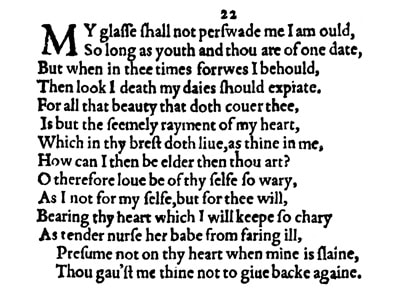

My glass shall not persuade me I am old,

So long as youth and thou are of one date, But when in thee time's furrows I behold, Then look I death my days should expiate; For all that beauty that doth cover thee Is but the seemly raiment of my heart, Which in thy breast doth live, as thine in me; How can I then be elder than thou art? O therefore, love, be of thyself so wary, As I, not for myself, but for thee will, Bearing thy heart, which I will keep so chary, As tender nurse her babe from faring ill. Presume not on thy heart when mine is slain, Thou gavest me thine, not to give back again. |

|

My glass shall not persuade me I am old

So long as youth and thou are of one date, |

My mirror – glass – will not persuade me that I am old for as long as youth and you are of the same age – are of one date – in other words, so long as you are young.

|

|

But when in thee time's furrows I behold

Then look I death my days should expiate; |

But when I start to see lines on your face, then will I look to death to absolve me from the sins of my days, in other words release me from life, because then I will accept that I am old.

|

|

For all that beauty that doth cover thee

Is but the seemly raiment of my heart, Which in thy breast doth live, as thine in me, |

Because all that beauty that covers you – of which I have spoken so much now in my sonnets – is just the tasteful, appropriate and fitting clothing worn by my heart, since much as your heart lives in my breast, my heart lives in your breast, and so your body with all your beauty effectively is the clothing for my heart.

|

|

How can I then be elder than thou art?

|

This being the case, how can I be older than you?

|

|

O therefore, love, be of thyself so wary

As I, not for myself, but for thee will, |

For this reason – because my heart lives in your breast – take such good care of yourself as I will take care of myself, not for my own sake, but for yours...

|

|

Bearing thy heart, which I will keep so chary

As tender nurse her babe from faring ill. |

...carrying your heart in my breast, which I will keep with so much care and attention – chary – as a tender nurse would devote to the baby entrusted to her, so as to keep it from coming to any harm.

|

|

Presume not on thy heart when mine is slain:

Thou gavest me thine, not to give back again. |

Do not presume to get your heart back when my heart dies or is killed: you gave me your heart never to be given it back again.

|

The superficially traditional and almost a little wistful sounding Sonnet 22 is the first one to address the age difference between William Shakespeare and his young lover and it is also the first one to expressly show us that – certainly as far as the poet is concerned and believes to understand – this love is mutual and reciprocated. Which makes this the third sonnet in quick succession to give us invaluable insights into Shakespeare's emotional world.

I, the poet, William Shakespeare look at myself in the mirror and although what I see would suggest that I am beginning to show signs of age, I do not feel that I have to accept them. The furrows or lines that time draws or carves into my face are not mentioned here, but they are hinted at by my saying that it is when I see them in you that I will welcome death because only then will age actually have any meaning for me. Of course, we have had the "deep trenches in thy beauty's field" of Sonnet 2 and "carve not with thy hours my love's fair brow" in Sonnet 19, so the idea that Time draws lines on us as we age is well established even within this sequence.

But for as long as you are young, I too am young, because my heart lives in you and so your beauty is like an outfit for my heart which means I cannot be older than you. While this does not logically follow, the sentiment is clear: as you have taken me into your heart in the same way that I have taken you into mine, we are on the same page and therefore age is irrelevant. And because my heart lives in you, you should be careful and protect yourself from harm, much as I will do the same, not because I don't want any harm to come to me, but because your heart similarly lives in me, and so I bear responsibility for its wellbeing and safety.

And then this in its own way quite devastating final couplet:

Presume not on thy heart when mine is slain:

Thou gavest me thine, not to give back again.

This, in tone sounds like both a declaration and a plea, and it may of course also be to some extent wishful thinking: we have asked the question before without being able to answer it: what does the young man make of all of this? And here we have someone who is clearly in love, who has laid his cards on the table and declared his passion for someone, telling him that as far as he is concerned, this love is for real and for good.

The two principal takeaways we receive from this lovely poem then are these: Firstly, William Shakespeare acknowledges that he is older than the young man. We have taken this as read for some time now, more or less since the beginning of the series, and certainly the fact that the young man is young is well established. But this is the first time I, the poet, position myself in relation to this youth, and by rhetorically asking 'how can I be older than you', I confirm what we've effectively known all along: I am older than you. How much older, we don't know, but we've set the parameters to between at least roughly ten to at most roughly twenty years older, depending on when exactly these particular sonnets are written and whom exactly they are addressed to. This does raise the fascinating question of age and what is a 'mature' or even 'old' age in Shakespeare's day, compared to today, and we will delve into this a little deeper a bit later in the series, because Shakespeare clearly is preoccupied with his age and refers to it on many more occasions.

Secondly, William Shakespeare suggests an emotional attachment on the young man's part that is equivalent to his own. Whether he has reason to do so or not we don't know: what we do know is that as far as I, the poet, am concerned, my heart lives in your breast, as yours does in mine, and you gave me your heart, not for me to give it back again. The fact that Shakespeare says this has happened does not mean that it has happened, but it does mean that he thinks it has happened, or at the very least wants to think that this has happened. And for anyone who has ever been head over heels in love with someone else this will not be in the least bit unfamiliar: how often do we project our own feelings onto someone else and interpret what they say or do in the way we want to understand it.

The reason I am flagging this up here as a possibility does not, however, lie in this sonnet. Sonnet 22 gives no real rise to doubt. But as soon as we glance only one or specifically two sonnets ahead, and then two or three further, we will realise that everything may not be as quite certain as it seems and as our poet clearly would wish...

I, the poet, William Shakespeare look at myself in the mirror and although what I see would suggest that I am beginning to show signs of age, I do not feel that I have to accept them. The furrows or lines that time draws or carves into my face are not mentioned here, but they are hinted at by my saying that it is when I see them in you that I will welcome death because only then will age actually have any meaning for me. Of course, we have had the "deep trenches in thy beauty's field" of Sonnet 2 and "carve not with thy hours my love's fair brow" in Sonnet 19, so the idea that Time draws lines on us as we age is well established even within this sequence.

But for as long as you are young, I too am young, because my heart lives in you and so your beauty is like an outfit for my heart which means I cannot be older than you. While this does not logically follow, the sentiment is clear: as you have taken me into your heart in the same way that I have taken you into mine, we are on the same page and therefore age is irrelevant. And because my heart lives in you, you should be careful and protect yourself from harm, much as I will do the same, not because I don't want any harm to come to me, but because your heart similarly lives in me, and so I bear responsibility for its wellbeing and safety.

And then this in its own way quite devastating final couplet:

Presume not on thy heart when mine is slain:

Thou gavest me thine, not to give back again.

This, in tone sounds like both a declaration and a plea, and it may of course also be to some extent wishful thinking: we have asked the question before without being able to answer it: what does the young man make of all of this? And here we have someone who is clearly in love, who has laid his cards on the table and declared his passion for someone, telling him that as far as he is concerned, this love is for real and for good.

The two principal takeaways we receive from this lovely poem then are these: Firstly, William Shakespeare acknowledges that he is older than the young man. We have taken this as read for some time now, more or less since the beginning of the series, and certainly the fact that the young man is young is well established. But this is the first time I, the poet, position myself in relation to this youth, and by rhetorically asking 'how can I be older than you', I confirm what we've effectively known all along: I am older than you. How much older, we don't know, but we've set the parameters to between at least roughly ten to at most roughly twenty years older, depending on when exactly these particular sonnets are written and whom exactly they are addressed to. This does raise the fascinating question of age and what is a 'mature' or even 'old' age in Shakespeare's day, compared to today, and we will delve into this a little deeper a bit later in the series, because Shakespeare clearly is preoccupied with his age and refers to it on many more occasions.

Secondly, William Shakespeare suggests an emotional attachment on the young man's part that is equivalent to his own. Whether he has reason to do so or not we don't know: what we do know is that as far as I, the poet, am concerned, my heart lives in your breast, as yours does in mine, and you gave me your heart, not for me to give it back again. The fact that Shakespeare says this has happened does not mean that it has happened, but it does mean that he thinks it has happened, or at the very least wants to think that this has happened. And for anyone who has ever been head over heels in love with someone else this will not be in the least bit unfamiliar: how often do we project our own feelings onto someone else and interpret what they say or do in the way we want to understand it.

The reason I am flagging this up here as a possibility does not, however, lie in this sonnet. Sonnet 22 gives no real rise to doubt. But as soon as we glance only one or specifically two sonnets ahead, and then two or three further, we will realise that everything may not be as quite certain as it seems and as our poet clearly would wish...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!