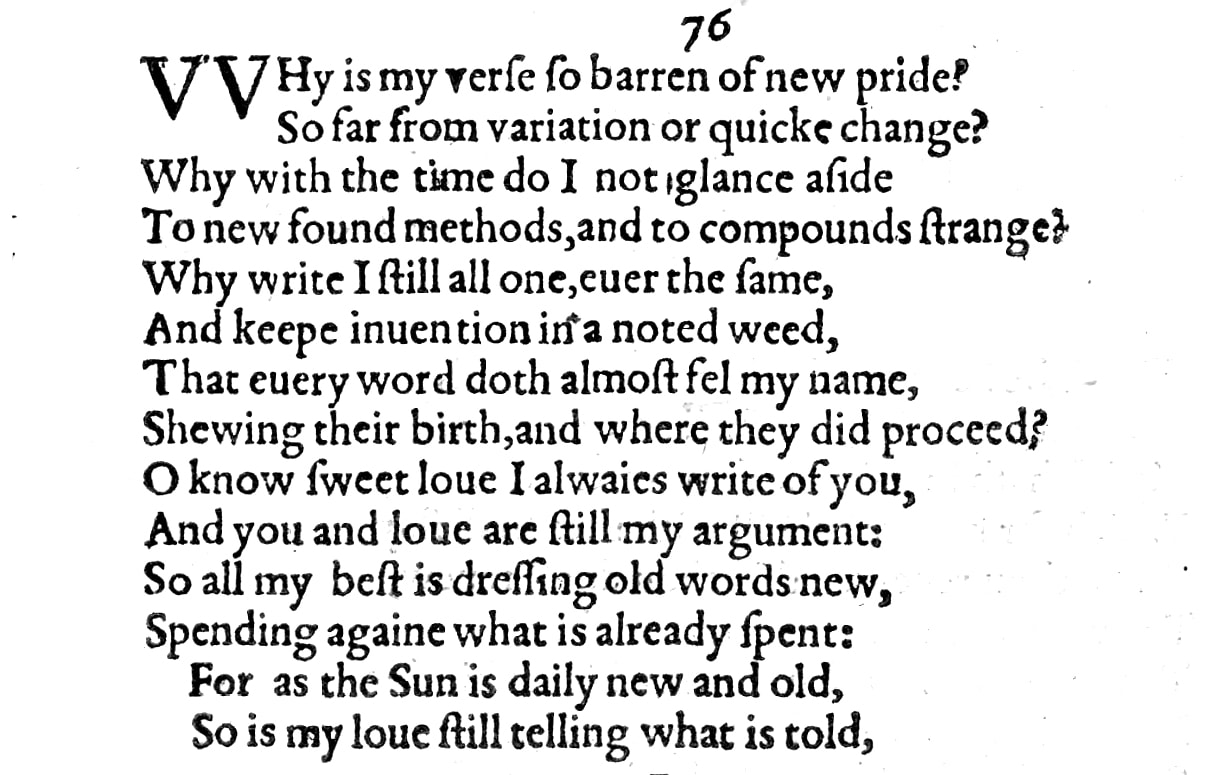

Sonnet 76: Why Is My Verse so Barren of New Pride?

|

Why is my verse so barren of new pride,

So far from variation or quick change? Why with the time do I not glance aside To new-found methods and to compounds strange? Why write I still all one, ever the same, And keep invention in a noted weed, That every word doth almost tell my name, Showing their birth and where they did proceed? O know, sweet love, I always write of you, And you and love are still my argument; So all my best is dressing old words new, Spending again what is already spent: For as the sun is daily new and old, So is my love still telling what is told. |

|

Why is my verse so barren of new pride,

|

How is it that the poetry that I write is so devoid of any new – and here we can take 'new' to mean 'new-fangled' or 'modern', or, at the time when Shakespeare is writing this, 'fashionable' – style that is also, by virtue of the fact that it is imbued with pride, implied to be showy or flashy. In other words: why is my poetry not more like the kind of poetry that is currently being celebrated?

The Oxford English Dictionary definition of 'pride' that is applicable here is "ostentatious adornment or ornamentation," which suggests an overblown verbosity and insincerity, or hyperbole, something Shakespeare patently disapproves of and feels, quite rightly, is beneath him. As early as Sonnet 21 he compares his truthful style to the ridiculous kinds of comparisons made by other poets between their subjects and everything excellent under the sun, including the sun. |

|

So far from variation or quick change?

|

The question continues: how is it that my poetry is so lacking any lively, nimble variety? Being able to express yourself with great 'variation' and finding a range of 'proofs' to make your argument is part of the art of rhetoric, and Shakespeare here contrasts his poetry to that of other poets who – implied again is in an attempt to show off – employ all manner of witty and elaborate ways to embellish their verse.

|

|

Why with the time do I not glance aside

To new-found methods and to compounds strange? |

How is it that as times and fashions change, I do not quickly or sharply turn or spring away from my trodden path and embrace or adopt these new approaches to composing poetry and these new words and word creations?

The time in which Shakespeare writes is one of language creation: Modern English is given birth to by him and his contemporaries, and one of the reasons we today credit Shakespeare with coining so many terms and phrases is that he was so prolific and so much of his output survives. But he was not working in isolation and here he in fact distances himself from his fellow poets who drive the language forward at breakneck speed by making up words. Both John Kerrigan and Colin Burrow interpret 'glance aside' not as we would today to mean 'look sideways' but "to move rapidly," sideways although I consider it more than likely that Shakespeare has both meanings in mind as they both make sense in the context, and they also point to the idea of 'compounds' here being contrasted in medicinal terms with 'simples', whereby 'simples' are drugs or remedies made by extracting the active agents in a single substance, while 'compounds' are made from a range of substances that, in combination, may have unpredictable and potentially dangerous effects. Whether Shakespeare means to allude to this, we cannot know, but there is a satisfying if subtle irony in the fact that 'compound' itself is a new word at the time, and so Shakespeare is here demonstrating what he says his poetry lacks by using that very thing, a new, maybe modish, word. |

|

Why write I still all one, ever the same,

And keep invention in a noted weed, |

How is it that I always and forever write the same thing in the one vein, and dress my topics in such a familiar style?

'Invention' here too refers to the art of rhetoric, where inventio does not – as we might be tempted to read it today – involve making up things, but finding the existing arguments for an oration or, as is the case here, a poem. We have come across this before, in Sonnet 48, where Shakespeare asks the young man, rather rhetorically, of course: How can my muse want subject to invent While thou dost breathe that pourst into my verse Thine own sweet argument, too excellent For every vulgar paper to rehearse? And the 'noted weed' here is a well-noted, and therefore known and respected, familiar, but also by necessity thus well-worn garb or garment or style in which the argument is thus metaphorically 'dressed'. 'Still' here, as so very often in Shakespeare and as indeed in the next couple of instances in this poem, means 'always'. |

|

That every word doth almost tell my name,

Showing their birth and where they did proceed? |

And I do this – always write the same thing in the same way – so much so that every word I produce almost tells my name, and all these words together are practically capable of telling the listener or reader where they stem from, whose pen has given birth to them: namely mine.

Noteworthy is that Shakespeare here not only concedes that his sonnets – at least according to him or to the person, real or imagined, who might criticise him – lack variety and new formulations that correspond to the fashion of the day, but that he in the same breath also marks out his style as identifiably his. |

|

O know, sweet love, I always write of you

And you and love are still my argument; |

And here is the answer to all these questions:

O know, dear, beautiful lover of mine, I always write of you, and you and the love I have for you are always the subject of my poetry. 'Argument' unsurprisingly here too is understood in the sense of the art of rhetoric, meaning the substance of that which is being discussed. |

|

So all my best is dressing old words new,

Spending again what is already spent: |

And so this being the case – you and love always being the subject of my verse – the best I can do is dress old words new: say the same thing over again, arrange the same words in slightly different ways, and in doing so expending efforts or writerly capital, if you like, that I have already spent or used before.

|

|

For as the sun is daily new and old,

So is my love still telling what is told. |

And the reason why this is so is simple enough: Just as the Sun appears glorious and fresh and new every day in the morning even though it is of course the same old and unchanging Sun, so the love that I bear you is always expressing what has already been expressed: my everlasting, daily rejuvenated, undying devotion to you.

By comparing it to the Sun, Shakespeare spells out not only the permanence, the dependable timelessness of his love for the young man, but also its unmatched power and quality, which is, of course, reflected in his unchanging poetry. |

The deceptively unsensational Sonnet 76 asks a simple question and provides to this a straightforward enough answer that will hardly come as a surprise: how is it that I write one sonnet after another and they all sound the same? Because "I always write of you." With this one declaration it settles a debate that – in view of its very existence bafflingly – has more recently reappeared in scholarly circles: are these sonnets, such as we have them in the collection originally published in the Quarto Edition of 1609, addressed to or written about principally one person, or could they not also have been composed in the context of a whole raft of relationships over a much longer period than has generally been assumed?

Sonnet 76 cannot speak to all of the 154 Sonnets, and we know for certain that in the second half of the series there is at least one other character who enters the scene, the woman usually referred to as The Dark Lady. While Shakespeare himself never calls her that, she is first mentioned as an identifiably separate subject in Sonnet 127. Whether or not she may also be the mistress with whom Shakespeare's young man has had the affair that features between Sonnet 33 and Sonnet 42 is a separate matter, which of course we shall look into closely when we come to her.

Sonnet 76 can and does speak to a multitude of sonnets. It does not spell out how many, but if we take ourselves away for a moment from the earnest examination of abstract possibilities and immerse ourselves in the reality of a working playwright, poet, actor, husband, father, and lover, then two things strike us as immediately obvious: our William is a busy man and he is prolific. His output is fast, on occasion also furious, and when it comes to these sonnets, heartfelt. And for a human being who makes a living with words to ask, "why write I still all one, ever the same," to the point where we see a pattern, where the words themselves reveal their author, because they always talk of the same thing in the same manner, he has to have been writing to the same person over many, many poems.

How many is many? Well, how long is a proverbial piece of string. But looking at the sheer volume of poetry this man produces, for any to register as many, there have to be a lot. So far, we have looked at 76 sonnets, including this one, and not once have we found a strong signal that here the tone changes so much that it really sounds like we are talking to or about someone else. There have been ups and downs, there have been outbursts of frustration and rage, there was the magnificent rant in Sonnet 66 and before that in Sonnet 56 a tender appeal to love itself, there was the sheer wonder of Sonnet 53 and the rare sarcasm of 57 & 58. There has been the inward assessment of self with Sonnet 62 and the deeply touching reflections on mortality with Sonnets 73 & 74. Not one of these sonnets demands to be read in the context of a different relationship. True enough, taken in isolation and in theory some of them could be written to or about or in response to emotions felt for another man. Some even – taken in isolation and in theory – could be written to or about or in response to emotions felt for a woman. Would that make sense?

O know, sweet love, I always write of you.

Well, someone might just pipe up at this particular moment, and say: what if 'sweet love' here is generic, what if this is whoever the sweet love of the moment happens to be.

And you and love are still my argument.

You, my love, as in my lover, as in the person I am writing this particular sonnet to, and love, as in love, the emotion, the state of being in love, the capacity of the human condition to feel, give, and be love, these two separate but entwined entities here both identified, are always my argument.

Could there be an exception to this, yes there could be. That would be the exception. We haven't come across it yet but chances are that at some point we shall.

William Shakespeare, the man who may or may not have collated these sonnets into the 1609 Quarto Edition, but who most certainly wrote these sonnets and who was alive when the Quarto Edition was published is telling the recipient of this sonnet that he always writes of them. Could this person be a different person to the person he always writes of? In what universe would that be a reasonable assumption to make?

Try to imagine this in a world of real people: you are trying to establish yourself as a playwright and poet in the city that is the epicentre of your language and of your theatre, you fall head over heels in love with a man – clearly a man, going by any number of these sonnets – you write sonnets to, for, and about him, you reach a point in your sonneteering where you realise, I aways write of you. Who is this 'you' likely to be? I would place my last pound on eleven out of twelve ten year olds being able to point to the young man, with the twelfth one being mischievous. There is always one.

In the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. We do not quite have certainty here, there is always a possibility that we have got the wrong end of the stick, that the improbable is actual and the obvious is simply blinding us, but listening, reading, relating to these sonnets as we do with what we have, which are the words, and with what makes sense and what constellates coherently, we can, by now, and with Sonnet 76 sealing this as tightly as any sonnet written more than four hundred years ago will ever be able to, state: these sonnets, all of the sonnets we have encountered so far, from the first 17 right through to here, are dealing with one single fabulous fascination: a young man, commonly referred to as The Fair Youth.

And this in itself is not without its own consequence. The young man who embodies this fascination, this young lover, this Fair Youth: we may not know for certain who it is, but we know to quite an appreciable level what he's like. He has the attention span of a 21 year old socialite with millions of expendable income at his disposal, and he is getting bored.

Because why would Shakespeare concede that he is repeating himself? Quite possibly out of ennui with his own lack of 'variation or quick change'. But as possibly because he's been told so. Now, Sonnet 76 does not actually suggest this, and staying true to our approach of listening to the words and the words only, we need to hold off for just a very short bit, because Sonnet 76 could quite conceivably simply stem from Shakespeare's own dissatisfaction with his own writing. But very soon, starting with Sonnet 78, it will become clear that our Will is not defending his monotony – which by the way is of course nowhere near as dull as he makes it out to be: we have seen and heard a tremendous range of registers, just to acknowledge this properly too – purely out of his own self-critical awareness, but because the young lover prompts him to: he has a new poet writing to and for him, and he leaves Shakespeare in no doubt that this other poet, at this point in the proceedings, is being preferred.

Sonnet 76 cannot speak to all of the 154 Sonnets, and we know for certain that in the second half of the series there is at least one other character who enters the scene, the woman usually referred to as The Dark Lady. While Shakespeare himself never calls her that, she is first mentioned as an identifiably separate subject in Sonnet 127. Whether or not she may also be the mistress with whom Shakespeare's young man has had the affair that features between Sonnet 33 and Sonnet 42 is a separate matter, which of course we shall look into closely when we come to her.

Sonnet 76 can and does speak to a multitude of sonnets. It does not spell out how many, but if we take ourselves away for a moment from the earnest examination of abstract possibilities and immerse ourselves in the reality of a working playwright, poet, actor, husband, father, and lover, then two things strike us as immediately obvious: our William is a busy man and he is prolific. His output is fast, on occasion also furious, and when it comes to these sonnets, heartfelt. And for a human being who makes a living with words to ask, "why write I still all one, ever the same," to the point where we see a pattern, where the words themselves reveal their author, because they always talk of the same thing in the same manner, he has to have been writing to the same person over many, many poems.

How many is many? Well, how long is a proverbial piece of string. But looking at the sheer volume of poetry this man produces, for any to register as many, there have to be a lot. So far, we have looked at 76 sonnets, including this one, and not once have we found a strong signal that here the tone changes so much that it really sounds like we are talking to or about someone else. There have been ups and downs, there have been outbursts of frustration and rage, there was the magnificent rant in Sonnet 66 and before that in Sonnet 56 a tender appeal to love itself, there was the sheer wonder of Sonnet 53 and the rare sarcasm of 57 & 58. There has been the inward assessment of self with Sonnet 62 and the deeply touching reflections on mortality with Sonnets 73 & 74. Not one of these sonnets demands to be read in the context of a different relationship. True enough, taken in isolation and in theory some of them could be written to or about or in response to emotions felt for another man. Some even – taken in isolation and in theory – could be written to or about or in response to emotions felt for a woman. Would that make sense?

O know, sweet love, I always write of you.

Well, someone might just pipe up at this particular moment, and say: what if 'sweet love' here is generic, what if this is whoever the sweet love of the moment happens to be.

And you and love are still my argument.

You, my love, as in my lover, as in the person I am writing this particular sonnet to, and love, as in love, the emotion, the state of being in love, the capacity of the human condition to feel, give, and be love, these two separate but entwined entities here both identified, are always my argument.

Could there be an exception to this, yes there could be. That would be the exception. We haven't come across it yet but chances are that at some point we shall.

William Shakespeare, the man who may or may not have collated these sonnets into the 1609 Quarto Edition, but who most certainly wrote these sonnets and who was alive when the Quarto Edition was published is telling the recipient of this sonnet that he always writes of them. Could this person be a different person to the person he always writes of? In what universe would that be a reasonable assumption to make?

Try to imagine this in a world of real people: you are trying to establish yourself as a playwright and poet in the city that is the epicentre of your language and of your theatre, you fall head over heels in love with a man – clearly a man, going by any number of these sonnets – you write sonnets to, for, and about him, you reach a point in your sonneteering where you realise, I aways write of you. Who is this 'you' likely to be? I would place my last pound on eleven out of twelve ten year olds being able to point to the young man, with the twelfth one being mischievous. There is always one.

In the absence of certainty, likelihood is our friend. We do not quite have certainty here, there is always a possibility that we have got the wrong end of the stick, that the improbable is actual and the obvious is simply blinding us, but listening, reading, relating to these sonnets as we do with what we have, which are the words, and with what makes sense and what constellates coherently, we can, by now, and with Sonnet 76 sealing this as tightly as any sonnet written more than four hundred years ago will ever be able to, state: these sonnets, all of the sonnets we have encountered so far, from the first 17 right through to here, are dealing with one single fabulous fascination: a young man, commonly referred to as The Fair Youth.

And this in itself is not without its own consequence. The young man who embodies this fascination, this young lover, this Fair Youth: we may not know for certain who it is, but we know to quite an appreciable level what he's like. He has the attention span of a 21 year old socialite with millions of expendable income at his disposal, and he is getting bored.

Because why would Shakespeare concede that he is repeating himself? Quite possibly out of ennui with his own lack of 'variation or quick change'. But as possibly because he's been told so. Now, Sonnet 76 does not actually suggest this, and staying true to our approach of listening to the words and the words only, we need to hold off for just a very short bit, because Sonnet 76 could quite conceivably simply stem from Shakespeare's own dissatisfaction with his own writing. But very soon, starting with Sonnet 78, it will become clear that our Will is not defending his monotony – which by the way is of course nowhere near as dull as he makes it out to be: we have seen and heard a tremendous range of registers, just to acknowledge this properly too – purely out of his own self-critical awareness, but because the young lover prompts him to: he has a new poet writing to and for him, and he leaves Shakespeare in no doubt that this other poet, at this point in the proceedings, is being preferred.

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!