Sonnet 2: When Forty Winters Shall Besiege Thy Brow

|

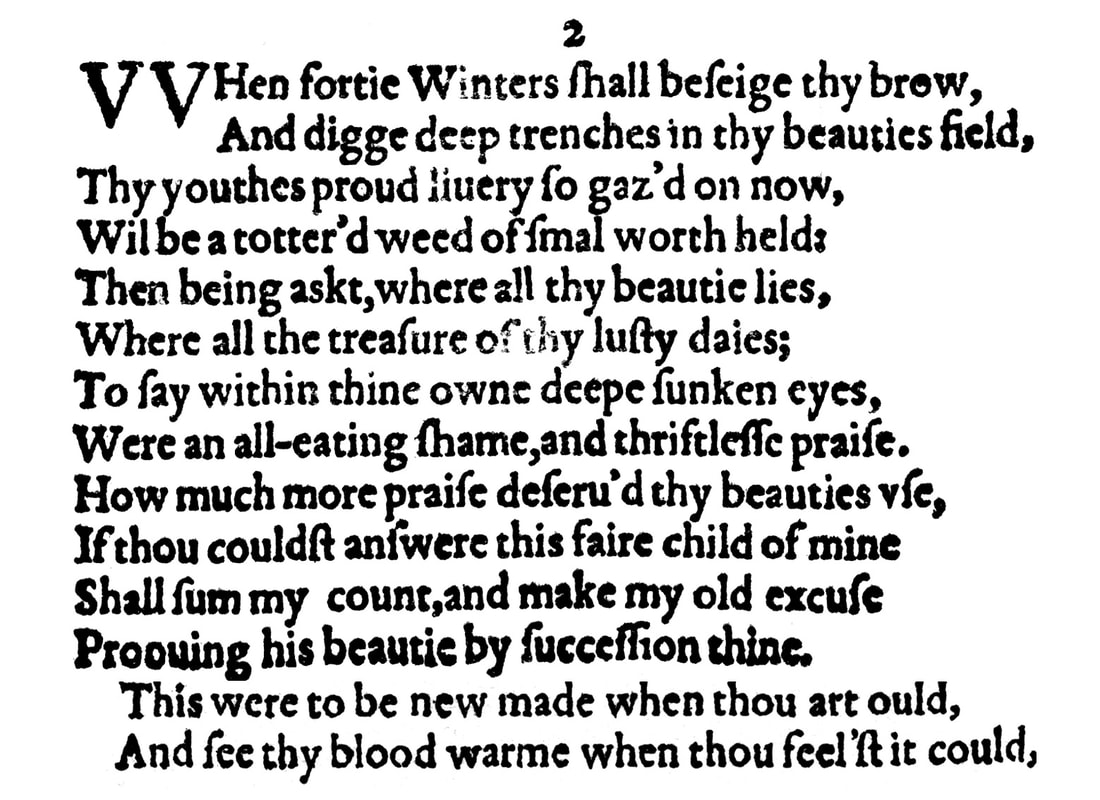

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty's field, Thy youth's proud livery, so gazed on now, Will be a tattered weed, of small worth held. Then, being asked where all thy beauty lies, Where all the treasure of thy lusty days, To say, within thine own deep-sunken eyes, Were an all-eating shame and thriftless praise. How much more praise deserved thy beauty's use If thou couldst answer: 'This fair child of mine Shall sum my count and make my old excuse', Proving his beauty by succession thine. This were to be new made when thou art old, And see thy blood warm, when thou feelst it cold. |

|

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow

|

When forty years have passed and bear down on you. "Besiege thy brow" is a beautifully poetic way of expressing not only that time passes, but also that it leaves its effect on you and effectively wages a war against you.

|

|

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty's field,

|

The passing years draw lines on your face – "thy beauty's field" – and these lines now are deep trenches: Shakespeare continues the image of a warfare, and these forty winters or years are not going to go anywhere: they are now firmly 'entrenched'.

|

|

Thy youth's proud livery, so gazed on now,

|

A 'livery' is a uniform "worn by a servant, an official, or a member of a City Company" (Oxford Dictionaries), such as a yeoman of the guard, so Shakespeare now departs from the military metaphor. "Thy youth's proud livery" then is the proud attire of the young man's youth, which is "so gazed on now," meaning it is so much looked on and therefore also admired.

The personification of an abstract concept – here youth, which is given a livery to wear, as if youth were itself a person – is very common in poetry generally and in Shakespeare in particular. He will, in the course of the sonnets, be talking about Time, Death, and Beauty, among others in this way, sometimes capitalising the word to emphasise this personification, sometimes not. |

|

Will be a tattered weed, of small worth held.

|

'Weed' here stands for basic or simple clothing or garments and is quite common in Shakespeare.

The Quarto Edition, incidentally, has 'totter'd' which is simply an old spelling of 'tattered', and some editors choose to retain this. |

|

Then, being asked where all thy beauty lies,

|

Then, when you are that old and your youth has gone and lost its much admired appearance, when somebody asks you where is your beauty now...

|

|

Where all the treasure of thy lusty days,

|

...where, indeed, is everything you valued – the treasure – in your days of young exuberance and energy.

"Lusty" is of course lustful but also more generally joyous, whereas "treasure" here may also be an allusion to sex and sexual effusions. In Sonnet 1, Shakespeare said to the young man, thou, "within thine own bud buriest thy content" and later he will encourage him to "make sweet some vial, treasure thou some place with beauty's treasure," very strongly suggesting that 'beauty's treasure' is his procreative force, what we today would call his DNA, which is of course passed on through the act of procreation. |

|

To say, within thine own deep-sunken eyes,

|

Then to answer this question by saying, they — your beauty and the things your treasured in your youth – lie within your own eyes, which, on account of your age, are now deep and sunken-in...

|

|

Were an all-eating shame and thriftless praise.

|

...would be a consuming or complete shame and amount to wasted – therefore inappropriate and unjustified, pointless – praise.

|

|

How much more praise deserved thy beauty's use

|

How much more praise would the use or application of your beauty (which again, by implication may well suggest the young man applying his sexual prowess) deserve...

|

|

If thou couldst answer: 'This fair child of mine

Shall sum my count and make my old excuse', |

...if you could answer by saying: 'this beautiful child of mine shall settle all my dues or add up to the sum of my life and thus be the fully justified excuse for my old age'.

|

|

Proving his beauty by succession thine.

|

His, the child's beauty, also belongs to you, by virtue of the fact that he is your child.

This is the first time we hear the child referred to as male, but it is clear from the outset that the principal aim of these first seventeen sonnets is to convince the young man that he needs an heir, which in Elizabethan England would absolutely be understood to be a son, since a succession can only go down the male line in this culture. |

|

This were to be new made when thou art old

And see thy blood warm, when thou feelst it cold. |

This would be like being newly born when you are old, and it would allow you to see yourself in your son – your blood – warm and alive and young at a time when your own blood starts to feel cold: when you are old and weak and fading.

|

Sonnet 2 continues the poet's mission to convince the young man of the need to produce an heir. And from today's perspective two things are particularly noteworthy.

First, the perception of old age: Shakespeare paints a picture of the young man at the age of forty – "when forty winters shall besiege thy brow" – as basically old. His "beauty's field" – his face – will be beset with deep trenches and the proud apparel of his youth will have turned into a tattered weed. Most of us today would smile at this, but life expectancy in Elizabethan England for a young male in London was approximately 30 years. If you got to forty, or, like Shakespeare himself, to 52, you did well (and Shakespeare himself spent the last few years of his life in the parochial peace of his native Stratford-upon-Avon).

Of course, people had the capacity to grow much older, and 'threescore years and ten' — 3 times 20 plus 10 being 70 — was considered a normal human lifespan. But with the plague, any number of other diseases, no science or modern medicine to speak of to cure injuries or illnesses, and extremely violent politics and near-constant warfare, your chances of actually making it there were slim.

This context is important in several ways. Firstly, the urgency with which the young man is being told to get on with it and produce an heir: he doesn't have forever; secondly, how the relationship between Shakespeare and the young man evolves. We will see that he considers himself to be much older and in the autumn if not indeed winter of his life at a time when he could not have been more than somewhere between his own early thirties and early forties, whereas the young man is considered and expressly described as being in the full springtime bloom of his youth, but in order to effectively start a family now he would have to be at least around 18 to 20.

The second thing worthy of note is that here we hear the child referred to for the first time as male. This is of unequivocal importance in Elizabethan England. Queen Elizabeth I's father, Henry VIII, famously went to extraordinary lengths to obtain a male heir. His six wives, whose fate the mnemonic catchily describes as 'divorced, beheaded, died; divorced, beheaded, survived' were entirely a consequence of this quest to produce a male heir, as indeed was the English Reformation which he instigated when he couldn't get his first marriage annulled by the Pope.

So who or whatever prompts Shakespeare to write these sonnets must have strong reason to do so and care greatly about the young man's succession, which suggests that the young man is either a first-born son or an only child. If he were the younger of several brothers, it would be nowhere near as important for him to procreate, and we will shortly get more and very intriguing evidence of this.

The young man is also, this much we learn from this sonnet, "so gazed on now:" And while it is entirely conceivable that somebody of little or no social status has their admirers, this is an early pointer towards somebody who is known to the world, who has the attention of the people around him, and who is generally viewed as beautiful. As we proceed and listen to these sonnets, we will be able to imagine much more clearly what kind of a person this young man is...

First, the perception of old age: Shakespeare paints a picture of the young man at the age of forty – "when forty winters shall besiege thy brow" – as basically old. His "beauty's field" – his face – will be beset with deep trenches and the proud apparel of his youth will have turned into a tattered weed. Most of us today would smile at this, but life expectancy in Elizabethan England for a young male in London was approximately 30 years. If you got to forty, or, like Shakespeare himself, to 52, you did well (and Shakespeare himself spent the last few years of his life in the parochial peace of his native Stratford-upon-Avon).

Of course, people had the capacity to grow much older, and 'threescore years and ten' — 3 times 20 plus 10 being 70 — was considered a normal human lifespan. But with the plague, any number of other diseases, no science or modern medicine to speak of to cure injuries or illnesses, and extremely violent politics and near-constant warfare, your chances of actually making it there were slim.

This context is important in several ways. Firstly, the urgency with which the young man is being told to get on with it and produce an heir: he doesn't have forever; secondly, how the relationship between Shakespeare and the young man evolves. We will see that he considers himself to be much older and in the autumn if not indeed winter of his life at a time when he could not have been more than somewhere between his own early thirties and early forties, whereas the young man is considered and expressly described as being in the full springtime bloom of his youth, but in order to effectively start a family now he would have to be at least around 18 to 20.

The second thing worthy of note is that here we hear the child referred to for the first time as male. This is of unequivocal importance in Elizabethan England. Queen Elizabeth I's father, Henry VIII, famously went to extraordinary lengths to obtain a male heir. His six wives, whose fate the mnemonic catchily describes as 'divorced, beheaded, died; divorced, beheaded, survived' were entirely a consequence of this quest to produce a male heir, as indeed was the English Reformation which he instigated when he couldn't get his first marriage annulled by the Pope.

So who or whatever prompts Shakespeare to write these sonnets must have strong reason to do so and care greatly about the young man's succession, which suggests that the young man is either a first-born son or an only child. If he were the younger of several brothers, it would be nowhere near as important for him to procreate, and we will shortly get more and very intriguing evidence of this.

The young man is also, this much we learn from this sonnet, "so gazed on now:" And while it is entirely conceivable that somebody of little or no social status has their admirers, this is an early pointer towards somebody who is known to the world, who has the attention of the people around him, and who is generally viewed as beautiful. As we proceed and listen to these sonnets, we will be able to imagine much more clearly what kind of a person this young man is...

This project and its website are a work in progress.

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!

If you spot a mistake or if you have any comments or suggestions, please use the contact page to get in touch.

To be kept informed of developments, please subscribe to the email list.

If you would like to donate, you can do so here. Thank you!